Local food ignored in council’s Climate Emergency Plan

By Patrick Francis

The impact of global warming on climate change is amongst the most discussed issue affecting the entire world’s natural and built environments. Its consequences are constantly in the news associated with sea ice and glaciers melting, increased incidence of natural disasters, increasing biodiversity loss, and negative impacts on human health.

Despite the publicity which reaches saturation during the annual world climate action summits the COPs, a November 2023 report “From Plate to Planet – how local governments are driving action on climate change through food” by the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES FOOD) contends that global action on the climate crisis is nowhere near the scale and commitment required to limit warming to 1.5C

“Urgent and far-reaching action to transform food systems is needed to reach the Paris Agreement target. Where national governments are falling short, this report shows how cities and regional governments are pioneering policies on food and climate change through dozens of inspiring examples of effective action on-the-ground”.

Given the impacts of climate change are becoming so real in Australia for both human habitation, the environment/biodiversity and agriculture it could be expected the report would contain examples from Australian local governments. In fact there are none! If the Macedon Ranges Shire Council’s recent Draft Climate Emergency Plan 2023 – 2030 is anything to go by it’s not hard to understand why. Despite being a rural shire with around 130,000 ha of farming and rural conservation zoned land adjacent to Australia’s second largest capital city, Melbourne with more than 5 million people (heading to 7 million by 2050), it pays little attention to local food production outside of what is happening to attract tourism for example vineyards and gourmet restaurants. In fact the words agriculture, livestock, crops, food miles are not mentioned in the Draft Strategy.

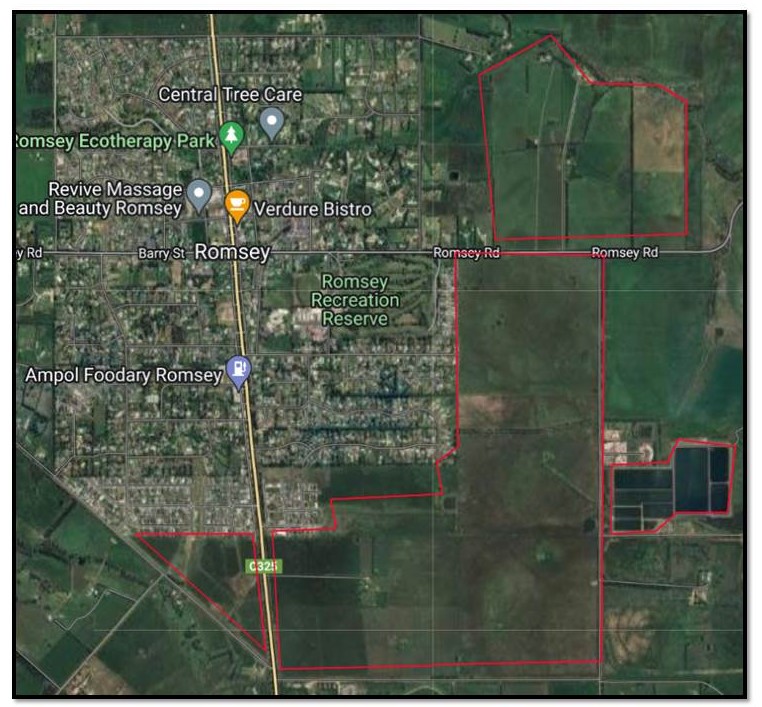

Failing to mention agriculture is one thing but the Shire has a number of town structure plans in the pipeline which propose removing high quality soil farming land from agriculture. For instance, the June 2023 Draft Romsey Structure plan has earmarked 393 ha of pastures adjacent to the Romsey township for housing development (read on this web site A climate emergency plan without targets is greenwashing – Moffitts Farm

Macedon Ranges Shire is not alone in neglecting agriculture in favour of housing, niche tourism and land banking. In The Guardian article of July 2023 Katherine Wilson writes “A spokesperson for the state government says it is “protecting Melbourne’s green wedges and peri-urban agricultural land, consistent with the metropolitan planning strategy, Plan Melbourne and our Biodiversity 2037 strategy”. But critics say planning decisions taken by successive governments are “causing incalculable harm” to fringe farmland systems.

Figure 1: In the Macedon Ranges the Draft Romsey Structure Plan has earmarked 232 ha of high quality farm land adjacent to the town’s waste water treatment plant (far right) for immediate housing development with another 161 ha of high quality farming land in a block to the north east for latter development. The state government and council have made no calculations of the impact of this development on greenhouse gas emissions, potential local food production, potential biodiversity and landscape amenity improvement, potential carbon abatement with re-afforestation, potential solar electricity generation and battery storage, and human well-being value. Source: Google Maps Area Calculator.

“There has probably never been a time of more fragmented governmental institutional and policy responses,” writes RMIT urban planning professors Michael Buxton and Andrew Butt in their 2020 book, The Future of the Fringe: The Crisis in Peri-Urban Planning. “Peri-urban planning is blighted by a classic policy deficit.”

Wilson also interviewed Dr Rachel Carey, lead researcher of the University of Melbourne’s Foodprint Melbourne project. “It’s not enough just to protect farmland,” Carey says “It’s important to incentivise landholders to grow perishable products – fresh fruit and vegetables – close to Melbourne, particularly with the shocks and stresses on our food systems.

“Cities are significant sources of waste that can be turned into fertilisers on farms. We’re using a small fraction of available wastewater to produce food: in the context of climate warming and drying, it makes sense to retain areas of fertile farmland close to the city and to water treatment plants. This is strategically important and should be central to policy thinking.”

The greenfields housing development pasture land adjacent to Romsey is also adjacent to the town’s waste water treatment plant, figure 1. Carey calls this strategically important land for food production, not housing.

Figure 2: Despite the Victorian state government stating it is protecting Melbourne’ s peri-urban farm land in green wedges thousands of hectares continue to be developed into housing estates. The Lomandra estate Romsey is a classic example. It is built on high quality deep basalt clay loam soil with a 720mm average rainfall which was formerly a dairy farm. The Macedon Ranges Shire Council continues to support such development and currently has a further 394ha of farmland to the north and east of Romsey earmarked for housing development. Photos: Patrick Francis and Google Earth

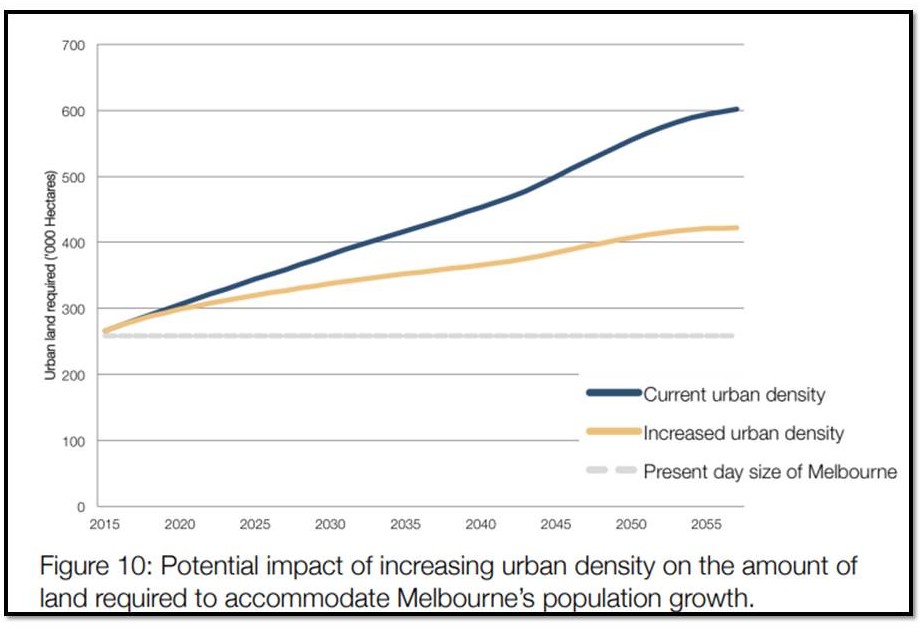

The Foodprint Melbourne Report highlights how the current peri-urban housing sprawl currently underway is devouring farming land, figures 2 and 3. It promotes increasing urban density rather than increasing urban area like what is proposed in the 2023 Romsey Structure Plan.

“If urban density were increased so that 80% of residential units became multiple dwelling units (townhouses and apartments) and the footprint of new buildings was reduced by 30%, urban sprawl could be reduced by about 50% by 2050 and 180,000 hectares of land in Melbourne’s foodbowl could be saved. This area of land is equivalent to almost 5 times Victoria’s vegetable growing land”, the Report states.

Figure 3A: Melbourne’s Foodprint Report identified a saving of 180,000 hectares of farm land which could be used for local food production, carbon abatement, biodiversity increase, landscape amenity and healthy living if urban housing density was increased rather increasing urban sprawl around Melbourne and adjacent towns. Source: Melbourne’s Foodprint Report.

Figure 3B: The current thinking in the Macedon Ranges Shire Council is further housing development on greenfields farming land adjacent to “growth” towns like Romsey (top). The 2023 Romsey Structure Plan ignored promoting higher density housing on large blocks within the existing Romsey town boundary where the infrastructure currently exists (bottom).

So what are other councils around the world doing to protect farm land from development so food production is maintained along with environmental improvement and reduction in greenhouse gas emissions? The International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food) wrote a report in November 2023 called “From plate to planet: How local governments are driving action on climate change through food”. It contained a range of examples of local governments taking action to protect farm land close to towns. Here are some examples.

* Catalonia, an autonomous region of Spain, has designed a governance model that includes a technical and operational committee tasked with reporting to the Catalan Food Council on the ongoing implementation of the 2021-2026 Food Plan. By positioning technical experts and community members to advise on progress, Catalonia’s collaborative governance design increases accountability, effectiveness, and citizen buy-in.

* The City of Bruges in Belgium uses a yearly carbon emissions accounting software to publicly monitor the City’s progress on its food plan. In addition to improving accountability, the platform also encourages participation by allowing residents to ‘join’ an action and contribute as community members. This level of transparency and openness not only builds trust between the government and residents, but also lowers barriers to participation.

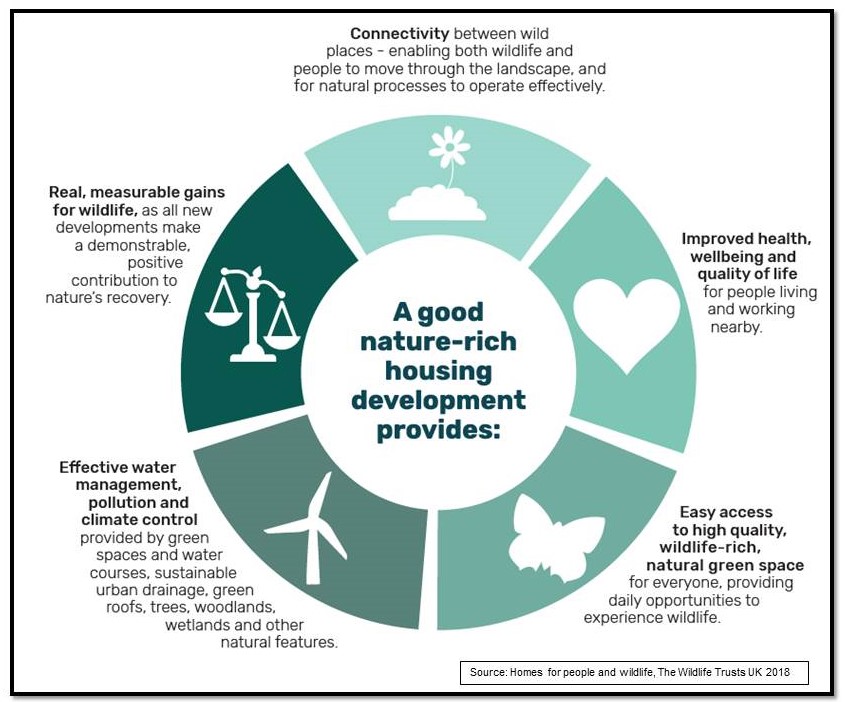

Many city governments have recognized the benefits to food security, rural livelihoods, biodiversity, and carbon sequestration of protecting ecosystems and farmland from urban development.

* The mega-city of São Paulo in Brazil is a world leader in this regard. The municipality has put in place a far-reaching farmland protection programme called Connect the Dots, which aims to protect the forests, reservoirs, and farms in rural districts on the outskirts of the city from urban development

* Mouans-Sartoux in France has a similar programme and has protected 112 hectares of farm land around the city from development, providing resources and funding for organic production in particular.

* The UK alliance for better food and farming, Sustain, runs the Every Mouthful Counts toolkit for Local Authorities, which has already helped 52 councils in the UK identify where significant food emissions can be cut. The toolkit provides estimates of the emissions reductions that various actions may deliver, as well as the co-benefits for public health and wellbeing, nature and biodiversity, local communities, and economic development.

Figure 4: Retaining farmland around towns is increasingly recognized around the world as critical for local food production and a host of co-benefits associated with the environment and human health. Source: The Wildlife Trusts UK.

The IPES- Food report concludes “pioneering local governments are recognizing and comprehensively addressing the complex interconnection between food and climate. They are key climate change policy implementers and innovators of actions that can be scaled up and replicated. They are integrating food actions into their climate plans, setting measurable targets, monitoring progress, merging environmental and social goals, supporting sustainable farming, promoting a shift to healthy sustainable diets, and slashing food loss and waste. Through a collaborative and whole food system approach, these local governments are reducing greenhouse gas emissions while delivering multiple co-benefits to their communities.”

The omission of any Australian local government examples in this report suggests that Dr Rachel Carey concerns around land use for food production and environmental enhancement close to cities is not taken seriously. This is despite the fact that most local governments in Victoria have declared a Climate Emergency as a result of the threat from global warming.

Box story

Melbourne’s Foodprint Report

Explores the environmental footprint of feeding the city and outlines the vulnerabilities in Melbourne’s regional food supply and strategies for addressing the vulnerabilities:

- It takes over 475L of water per capita per day to feed Melbourne, around double the city’s household usage

- 16.3 million hectares of land is required to feed Melbourne each year, an area equivalent to 72% of the state of Victoria

- Feeding Melbourne generates over 907,537 tonnes of edible food waste, which represents a waste of 3.6 million hectares of land and 180 GL of water

- Around 4.1 million tonnes of GHG emissions are emitted in producing the city’s food, and a further 2.5 million tonnes from food waste

- Key vulnerabilities in Melbourne’s regional food supply include loss of agricultural land, water scarcity and the impacts of climate change

- Potential strategies to increase the sustainability and resilience of Melbourne’s regional food supply include increasing urban density, shifting to regenerative agriculture, increasing the use of recycled water for agriculture, reducing food waste and modifying our diets

- Around 10% of the available recycled water from Melbourne’s water treatment plants would be enough to grow half of the vegetables that Melbourne eats

- Melbourne’s city foodbowl could play an important role in increasing the resilience and sustainability of the city’s food supply.

Find out more: Report: Melbourne’s Foodprint (unimelb.edu.au)