Air travel highlights climate change policies inconvenient truth

By Patrick Francis

As the Victorian Government and local councils allow farm land to become housing developments they ignore an inconvenient truth about anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. It’s the difference between the trajectory for greenhouse gas stocks in the atmosphere versus greenhouse gas flows into an out of the atmosphere. Put simply once a greenhouse gas is released into the atmosphere from a fossil fuel source such as aviation fuel it is never returned it just keeps adding to the total. In contrast a flow greenhouse gas such as methane from livestock (the major contributor GHG from agriculture) remains in the atmosphere for 10 – 14 years then converts into CO2 and returns from the atmosphere into plants and soil through photosynthesis. It is subsequently consumed by livestock and the cycle repeats.

So farm land management for a balance between food production and ecosystem services presents society with effective strategy alongside technology for reducing CO2 stock in the atmosphere or at least preventing the stock increasing above the 1.5C temperature increase threshold for climate change induced disasters – more cyclones, more droughts, more storms, more fires, more sea level rise, more food shortages.

Human activities which generate greenhouse gas stocks versus flows is not a difficult concept to understand, yet politicians conveniently ignore it when developing their local, state and federal net zero 2050 policies. The current housing crisis across Australia is an example. Immigration is encouraged at the expense of environmentally responsible housing developments. There are not enough homes so more farming land especially in peri-urban areas is released to developers. Every house that is built is accompanied by a contribution to CO2 stocks in the atmosphere via a range of mechanisms (concrete, materials transport, materials, earthworks, fossil fuel). And the further away developments are from transport infrastructure the greater their construction and ongoing household emissions.

But no developer is held to account for the amount of CO2 released to the atmosphere stockpile from each house built. No developer prices each house based on the contribution it building makes to the atmosphere’s CO2 stock. That’s inconvenient information, rather developers and government policies point to the house’s energy efficient rating. That’s sounds good but it ignores all the greenfields construction emissions.

And what about the ongoing emissions from families living in each house? The general estimate is that each household in Australia contributes 15 to 20 tonnes CO2e per year to the greenhouse gas stocks in the atmosphere. And the further away from capital cities the housing developments are built the higher the living household contribution is to the atmosphere.

What if the land on which all the new houses, roads, service facilities are built on stayed as farm land devoted to a balance between food production and ecosystem services like CO2 abatement through revegetation and agroforestry, biodiversity enhancement and clean water supply? And new housing developments were restricted to within existing suburban and town boundaries based on policies limiting population increase and encouraging higher housing density with a lower construction emissions blueprint?

The NSW premier said in February 2024 that the government was considering removing council planning powers if housing estates are not built around transport infrastructure. In Macedon Ranges Shire in Victoria the council is proposing converting in excess of 300 hectares of farm land adjacent to Romsey town into residential development doubling its population in 10 years despite no transport infrastructure being present.

The farm land ear marked for housing development if retained could continue to produce food in conjunction with carbon abatement and provide the opportunity for the shire to reduce its 571,000 tonnes CO2e carbon footprint. (Businesses and councils are already buying CO2 offsets generated by tree planting projects mostly in developing countries rather than on Australian farms because a tonne of CO2e is cheaper overseas.)

Figure 1: Farm land presents Australia with it most reliable means of greenhouse gas offsets through revegetation in conjunction with food production. Source Cathy Waters Charles Sturt University Graham Centre July 2021

These greenfield farm land housing developments are a greenhouse gas emissions source inconvenient truth ignored by politicians and local governments for decades. New houses, new freeways, new road tunnels, new stadiums, new schools, new shopping centres, higher GDP all win elections but each day add more CO2e to the atmosphere stock.

Perhaps the most inconvenient truth strategy for preventing more CO2 being added to the already high atmospheric stock is for the public to avoid air travel as much as possible. Air travel is one of the most politically ignored contributors to climate change which can be significantly reduced by lifestyle change. Around the world tourism is a major source of income for maintaining GDP but it comes with the cost of increasing greenhouse gas stock in the atmosphere. Airports are being expanded to accommodate increasing passenger demand for more flights more frequently to more destinations.

This is exemplified in the January 2024 edition of the Melbourne Airport Community Newsletter. The airport management is excited that passengers numbers are increasing for domestic and international flights after the 2020 to 2022 downturn due to Covid pandemic travel restrictions. In the six months to December 2023 domestic passengers increased 8% to 12,239,171 and international passengers increased 47% to 5,475,133.

The newsletter makes no mention of the greenhouse gas emissions associated with the flights these passengers take or the emissions generated across the airport for day to day operation and for building new car parks, roads, and an anticipated third runway.

But the emissions from flights in Australia are easily calculated from data available. This is what a Google search found:

The average carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions from domestic airline passengers in Australia can vary based on factors such as the type of aircraft, distance travelled, and passenger load. But estimates of emissions per passenger have been made. They are:

* A domestic flight emits approximately 246 grams of CO₂ per kilometre. Considering a typical flight distance, this translates to about 123 kilograms of CO₂ (442kg CO2e) emissions per passenger for a domestic flight

* The 24 million domestic passengers using Melbourne Airport in 2023 contribute

approximately 2,950,000 tonnes of CO2 (10,620,000 tonnes CO2e) to the atmosphere just in flights. They contribute more in travel to and from the airport.

(An average petrol caremits around170 grams of CO₂ per kilometre)

The 2023 domestic passenger emission from Melbourne airport are equivalent to the total emissions of an adding an additional 18 Macedon Ranges Shires for one year forever. And Melbourne Airport is adding a third runway by 2030 to accommodate more flights and passengers. It is expecting around 50 million domestic passengers will pass through the airport per year by 2044. On current emissions footprint that means the equivalent of adding approximately 38 Macedon Ranges Shires emissions into Victoria every year.

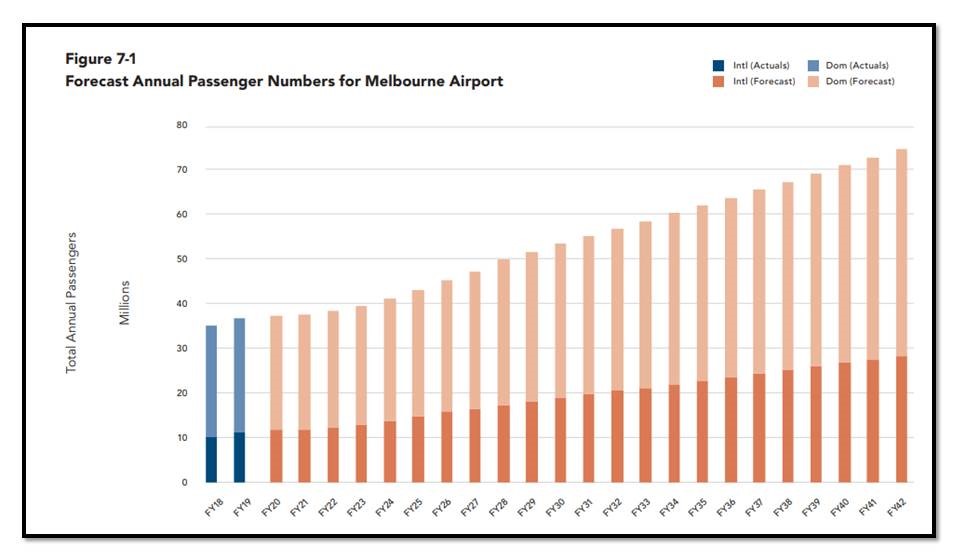

Figure 2A: Melbourne Airport is forecasting to double current passenger numbers across domestic and international flights between 2023 and 2044. Source: Melbourne Airport Master Plan 2022

Melbourne Airport describes emissions in its MR3 Major Development Plan “Chapter B11 Greenhouse Gas Emissions Summary of key findings: A detailed greenhouse gas emissions inventory has been prepared for the construction and operation of Melbourne Airport’s Third Runway (M3R). Construction emissions are estimated at 442,000 tonnes CO2e over the four years. The biggest source of emissions is from aircraft during the landing and take-off cycle (LTO). Melbourne Airport has a limited ability to implement measures to reduce these LTO-related emissions but will continue working with airlines to reduce greenhouse gas emissions wherever possible.”

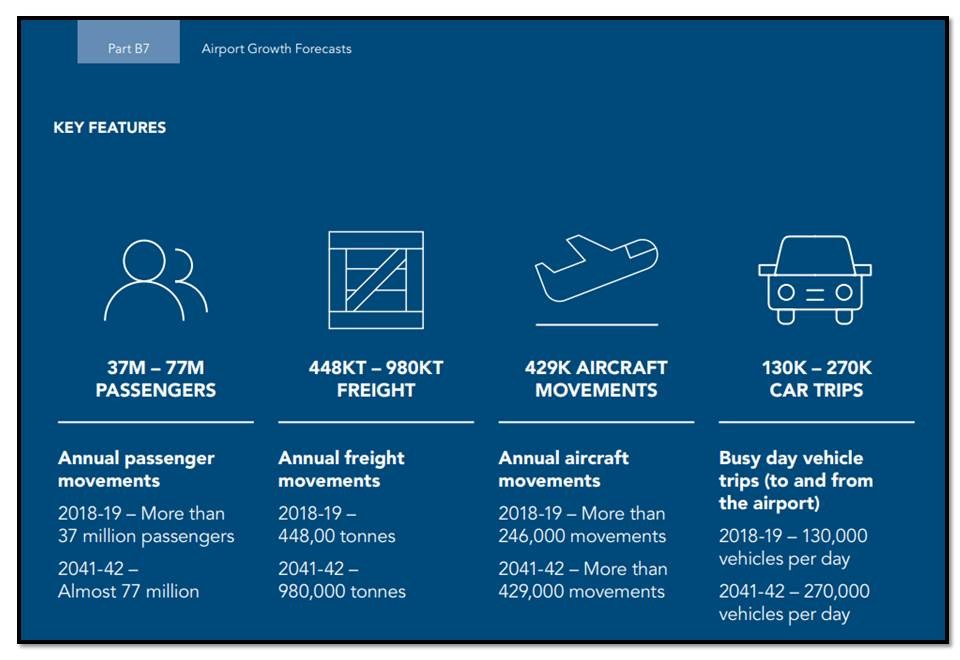

CEO Lorie Argus states in a promotional video that the third runway will see Melbourne Airport handle 76 million passengers in 2044 (34million in 2023) and that “Will inject billions of dollars into the state’s economy”. While the airports Master Plan does not provide data on estimates of additional emissions associated with the doubling of passengers an estimate can be made. The approximate 50 million domestic passengers using the airport will inject approximately 20,000,000 tonnes of CO2e into the atmosphere stock per year from their flights let alone the emissions associated with travel to and from the airport by both passengers and staff. The Melbourne Airport 2022 quantifies the impacts of expansion to 2044 but leaves out data around additional greenhouse gas emissions, Figure 2B.

Figure 2B. This Melbourne Airport growth forecasts summary ignores the additional greenhouse gas emissions to be generated from the increases in flights out of the airport as well as from car trips to and from the airport as its precinct expands. Source: Melbourne Airport Master Plan 2022

The Melbourne Airport Master Plan 2022 does address the airports own Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions and states it is planning to meet net-zero for these by the end of 2025. It strategies for achieving this include constructing a solar electricity farm and rooftop solar and offsetting emissions by supporting hydro power in Tasmania. Despite this Melbourne Airport is the operator of an enormous commercial centre with hundreds of businesses using it facilities all producing emissions and likely to increase those emissions as passenger numbers and trade increases.

Its Master Plan 2022 recognises that accommodating “…predicted passenger growth will result in an increasing demand on natural resources and potentially increased impacts on the environment (which) include increased carbon emissions and climate change impacts.”

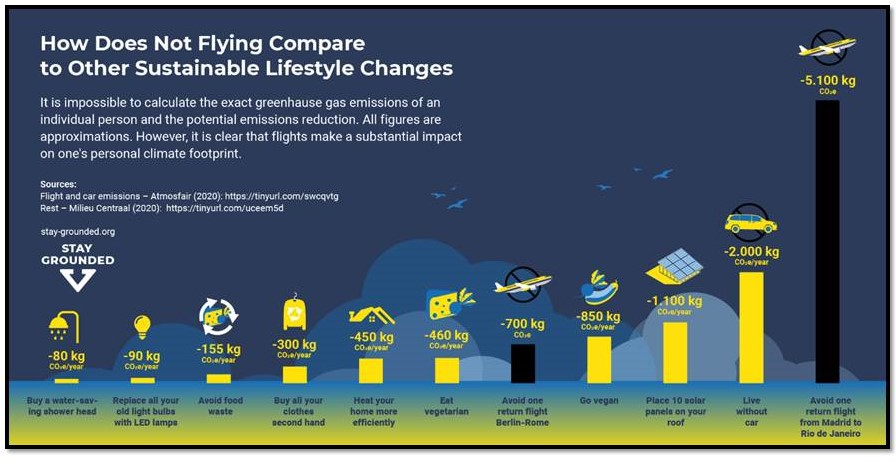

The only effective strategy to reduce the annual addition of CO2 to the existing atmospheric stock is for people to significantly reduce the number of domestic and international flights made each year. The organisation Stay Grounded highlights that of all strategies a person can implement to reduce his or her annual emissions the one with most impact is to stop flying, figure 3.

Figure 3: It is now recognised that avoiding domestic and international flights is one of the most effective lifestyle ways for an individual to prevent adding more CO2 to the existing atmosphere stock. The authors of this infographic do not understand that removing meat from the diet unlike not flying has little impact on total atmosphere CO2 stock, because livestock methane emissions convert to CO2 which is removed from the atmosphere by renewable photosynthesis in pastures the livestock eat and through re-vegetation on farms. Source: Stay Grounded.

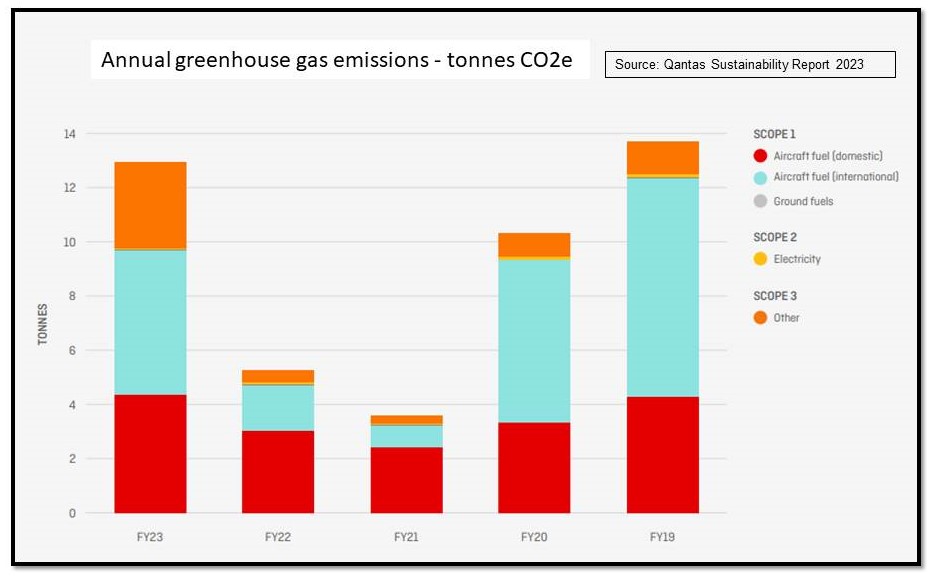

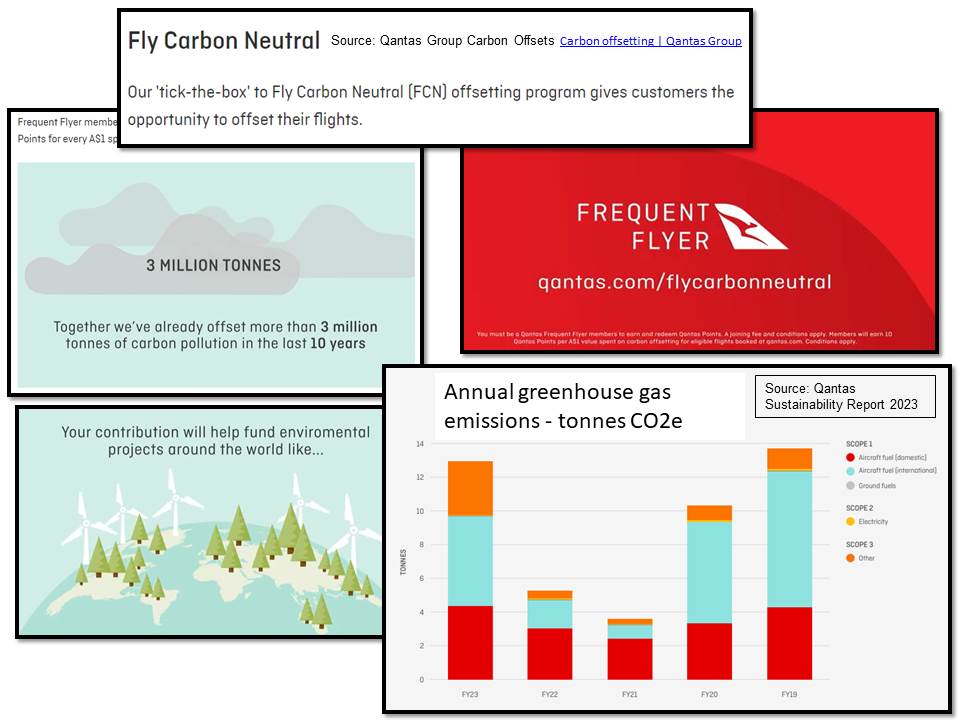

The Qantas Sustainability Report 2023 demonstrates the extent of impact reducing flights per year has on CO2 emissions. That’s because the around 90% of its annual total greenhouse emissions are derived from fossil fuel, figure 4. When the covid pandemic stopped international flights and reduced domestic flights in 2021, the company’s annual emissions dropped by approximately two thirds or 10 million tonnes CO2e.

Figure 4: The majority of Qantas greenhouse gas emissions are derived from aircraft fuel, when overseas flights stopped during the Covid pandemic the Company’s fuel emissions dropped from approximately 12 million tonnes CO2e to 3.5 million tonnes CO2e.

Qantas will be a major beneficiary of the Melbourne Airport doubling of passengers after the third runway is built. Its 2023 Sustainability Report makes no projections for the company’s emissions profile with increased passenger numbers. Unless the company can make significant inroads into Sustainable Aviation Fuel use then the prognosis is a doubling of the company’s emissions when passenger number double.

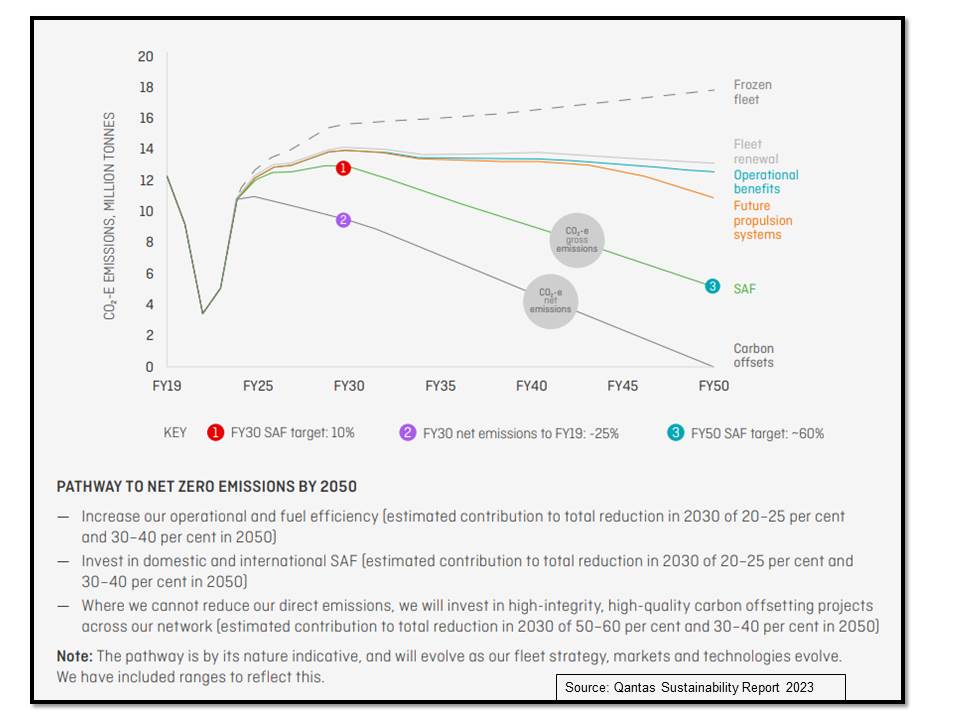

Despite a doubling of passengers the company contends that it can reduce its emission and be net zero emissions by 2050. It claims this will be achieved by the increased availability of blended fossil fuel with biofuel (Sustainable Aviation Fuel SAF) and offsetting all the outstanding fuel emissions with carbon abatement projects in Australia and overseas. Figure 5 shows the proposed greenhouse gas emissions trajectory to 2050.

The puzzling component of Figure 5 is the lack of increase in the company’s greenhouse gas emissions as passenger numbers head towards doubling in line with Melbourne Airports (and other major airports) projections for increased passengers associated with improved airport capacity. Using figure 4 data as a guide to total emissions Figure 5 suggest no change in emissions despite doubling passengers up to 2040. In other words Qantas contends technology will take care of any additional operation emissions and those that are not covered by this means will be offset through carbon abatement.

Figure 4: The Qantas Pathway to net zero emission by 2050 relies on a significant change in the availability of Sustainable Aviation Fuel which derived from converting plant and food waste materials into biofuel and blending it with fossil fuel, but mostly through purchasing carbon offsets.

Given Qantas is just one of hundreds of international and domestic airline companies all with similar plans to increase passengers year on year two issues are being ignored in their net zero emissions by 2050 claims.

Firstly SAF relies on building a worldwide biofuel industry. SAF will have to be available at every airport Qantas refuels its planes. According to Qantas “SAF is produced from certified bio feedstock, including used cooking oil, sugar cane, forestry residues, animal tallow and other waste products. It is blended with normal jet fuel and produces up to 80 per cent fewer emissions on a life cycle basis when compared with traditional jet kerosene.” With world population increasing to an anticipated 10billion by 2050, the availability of biomass to convert into biofuel is likely to decline with competition for biomass for fertiliser to maintain food productivity and soil health.

Secondly, demand for carbon abatement by large corporations and governments with limited opportunity to stop all emissions is likely to increase exponentially as policy and legal pressure mounts to be net zero by 2050. There is limited farm land available for credible tree planting and forest protection projects in geographic locations with the rainfall and soil type to support significant permanent carbon sequestration. This land is also the most desirable for food production and often for housing development especially in peri-urban and coastal districts. Farmers themselves will increasingly hold onto their carbon abatement from tree planting (known as insetting) as they will also need to demonstrate declining or zero emissions to markets purchasing their products. Selling credits to corporations means farmers cannot also claim use of the abatement generated on their farms.

In March 2022 Qantas stated in “Our plan to achieve net zero emissions by 2050” that it was entering a major integrated reforestation and carbon farming project in the Western Australian wheat belt.

“The project would see marginal farming land replanted with sustainable, drought-resistant native plant species, which aims to improve the environment and generate Australian carbon credits to help offset the three companies’ future carbon footprints. Longer term, it would also create a potential source for sustainable aviation fuel production from cut back mallee trees”.

Given that most farmers across the WA wheat belt have been revegetating their properties with tree corridors and blocks for soil conservation and salinity control for the last 30 years and more recently for insetting it is difficult to see Qantas achieving any significant CO2 abatement from this approach, figure 6A. As for sustainable biofuel from corridors of oil mallee trees, it has been tried in the past and failed due to cost not only for harvesting and processing but also for transport to storage facilities close to Perth. As well commercial growing and harvesting will not be confined to low production or degraded farm land. For optimum growth all trees including mallee need to be grown on quality soil in rows which enable machine harvesting, figure 6B. The same land is required for food crops.

The assumption that Australia and other countries have plenty of land for carbon abatement while the world population continues to increase may be incorrect. Net zero emissions by 2050 may put corporate and government demand for land based carbon sequestration on a collision course with farm land to produce enough food to feed the world.

Figure 6A: Conservation plantings and alleys to restore and enhance across farm ecosystem services on low production or saline affected areas on WA farms has been underway for three decades. Once balance is achieved further inroads in favour of tree planting will potentially lower grain production available for export. Photo: Patrick Francis 2004.

Figure 6B: Oil mallee for potential use in SAF as described by Qantas needs to be grown on productive farm land at an enormous scale so cost effective machine harvesting and oil processing can be undertaken. The benefit of harvesting oil mallee and other trees that coppice is that the SAF produced does not add to CO2 stock in the atmosphere because emissions are absorbed back into vegetation through photosynthesis. But it’s the same land food crops are grown on. Source: WA Oil Mallee Company 2006.

While Qantas is an example of an airline business that generates significant carbon emissions to supply a service, its customers have an opportunity to reduce their flight emissions. Qantas offers customers the opportunity to “offset their flights” and “fly carbon neutral”.

In the company’s Group Carbon Offsets document it states “together we’ve already offset more than 3 million tonnes of carbon pollution in the last 10 years”, figure 7. Given 3 million tonnes (assuming it is CO2e) is less than 25% of the company’s emissions in 2023 it seems airline customers have little interest in offsetting their trips emissions despite extensive and on-going publicity given to the climate crisis and the increasing incidence of natural disasters world-wide.

Figure 7: Qantas promote a “fly carbon neutral” line to frequent flyer customers but to do so is not currently possible.

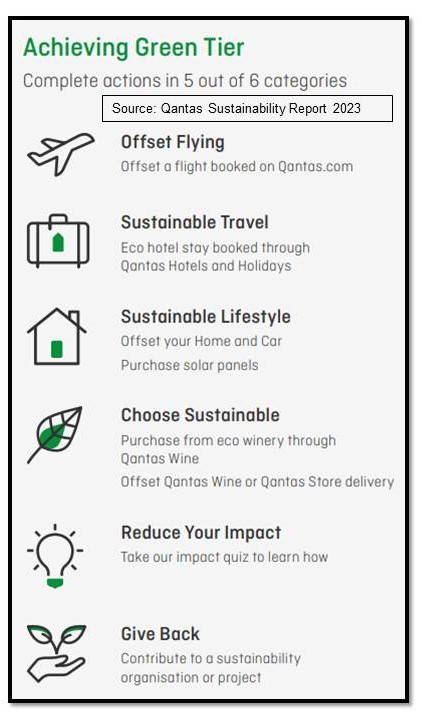

Another initiative promoted to Qantas frequent flyers is the Green Tier program launched in March 2022 and aimed at “…educating, encouraging and rewarding our 15 million Australian Frequent Flyer members for a range of activities including offsetting their flights, staying in eco-hotels and installing solar panels at home.”

To achieve Green Tier status frequent flyers must complete 5 out of 6 sustainable activities each year, figure 8. Four of the six activities have commercial connections to Qantas such Qantas hotel, Qantas wine.

Figure 8: Frequent flyer members achieving Green Tier status ensures Qantas gains more business income from its customers and carries more passengers generating more flights and more greenhouse gas emissions.

The reward for customers achieving Green Tier status is perverse. The concept is aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions but the reward for doing so is to produce more greenhouse gas emissions through benefits such as “bonus Qantas Points…and ability to earn Qantas bonus points when purchasing eligible sustainable products or experiences”.

The Qantas frequent fly member response to Green Tier has been muted. The company reported in 2023 that “More than 470,000 members have completed at least one activity towards achieving Green Tier.”

In other words just 3.1% of frequent flyer members are prepared to make a conscious effort to reduce emissions or offset their flight emissions. This real world outcome is at odds with University of Bonn, Germany, behavioural economist research published in February 2024 which found that nearly 69% of the global population would give up 1% of their household income to stop climate change. The research involved surveying nearly 130,000 people in 125 countries.

The significant difference between frequent flyers and survey respondents is action versus aspiration. Survey respondents are notorious for ticking the socially main stream box but if asked to act accordingly and pay more for a service or product, the percentage prepared to do so drops significantly.

Take home message

The inconvenient truth around achieving genuine net zero 2050 outcome is that lifestyle changes to reduce emissions that extend beyond the low hanging financial and mental rewarding actions (solar panels, electric vehicles) will be needed. Because some emissions cannot be avoided and will continue to increase atmospheric CO2 stock due to population increase, then farm land must be protected from development so it remains viable to produce food in conjunction with carbon abatement and biodiversity protection. Governments and businesses associated with ongoing emissions that rely on purchased abatement to meet net zero 2050 obligations may not be able to source sufficient credits as the land available to generate them becomes locked into environmentally sustainable food production and protecting ecosystem services. It might be inconvenient to reduce driving, use more public transport, walk more, lower household consumption, stop flying for holidays, build smaller higher density houses within existing suburban and town boundaries and buy locally produced food but the global warming consequences of not reducing our individual carbon footprint are becoming increasingly apparent.

SAF update 21 May 2024

Sustainable Aviation Fuel research given government grant

UniSA Aviation Professor Shane Zhang has been awarded a $230,000 National Foundation for Australia-China Relations grant to lead the project, exploring the commercial opportunities of using bio feedstock to replace conventional kerosene jet fuels with ‘green’ fuel.

Sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs) are still in their infancy, accounting for less than 1% of jet fuels worldwide, although the European Union (EU), Singapore, the US and UK are moving towards mandating SAFs within the next few years.

“Australia is among a handful of countries globally to support the transition to SAFs, but the financial commitment to develop a local industry does not extend to a mandate at this stage,” Zhang says.

This contrasts with the EU, which has mandated that 2% of all departing flights from Europe will use green fuels by 2025, up to 70% by 2050. Singapore has also set a 1% SAF target for all departing airlines from 2026, increasing to 3-5% by 2030, and the UK has mandated that 10% of its airline fleet use SAFs by 2030, increasing to 22% by 2024.

Airservices Australia has set a target of reducing CO2 emissions per flight by an average of 10% by 2030. Globally, aviation accounts for approximately 3% of global emissions, but this could rise to 22% by 2050 as more people fly and other sectors decarbonise more quickly, Zhang says.

“Unlike ground transportation, there are limited alternative fuel options for the aviation sector. Sustainable fuels are one of them, but they are up to five times more expensive than traditional fuel and airlines are reluctant to invest in them until they become cheaper and more readily available.

“Likewise, biotechnology companies need a guaranteed market from airlines before they commit to developing SAFs, so the hesitation runs both ways.”

Box story

The rickety carbon commodity

By Peter Donovan, USA Soil Carbon Coalition

Water cycling and carbon cycling are the two complementary legs on which climate change marches. The carbon leg has received the most attention. Understanding the carbon cycle mainly in terms of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere—carbon pollution, carbon footprint—leads to a simplified understanding of carbon cycling as a kind of balance, where emitting carbon dioxide into the atmosphere might be balanced or offset by carbon “sequestration” or “drawdown” in trees, soils, or rocks. Instead of the circle of life, carbon becomes a commodity.

This balance amputates the enormous complexity of carbon cycling to fit into our habits of narrow problem-solving, to fit into our legal, economic, political, and social architecture. In today’s world of rampant commodification, financialization, and enclosure of ecosystem “services” by big money and big environmental organizations, now abetted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, carbon “sequestration” has become a climate policy. Because fossil fuels are intrinsic to our economies and ways of life, most governments can’t restrain emissions, so they are supporting markets for carbon “offsets” that seek to reconcile competing claims: 1) the claims of carbon “sequestration” on land parcels—the supply—with 2) the demand, which is the needs of individuals, businesses, and governments to claim they are reducing their carbon footprint or acting against climate change.

Neither claim is solid.

The movements of the various forms of carbon through plants, soils, atmosphere, and seas are sometimes turbulent, often obscure, and not easily measured or tracked, especially as they shift over time in response to myriad influences including the solubility of carbon dioxide in seawater, the ocean’s biological carbon pump, complex dynamics of carbon in soil, and the susceptibility of biological carbon to oxidation through drought or fire. Even well-intentioned claims of sequestration or offsets rest on a rickety ladder of assumptions, ripe for profiteering, power grabs, and fraud. At either local or global scales, there is no way to tell if carbon sequestration is working to slow climate change.

Find out more:

Donovan’s full blog is at The trouble with carbon | Soil Carbon Coalition published February 2024

References:

NSW premier interview: NSW govt will ‘take’ councils’ planning powers away if no housing built: Chris Minns | Sky News Australia

1.5 Degree Lifestyle 1.5 Degree Lifestyles | Aalto University

Qantas Group Carbon Offsets Carbon offsetting | Qantas Group

Qantas Sustainability Report 2023 QAN_2023_Sustainability_Report.pdf (qantas.com)

Melbourne Airport Master Plan 2022 Melbourne Airport Final Master Plan 2022.pdf (kc-usercontent.com)

Climate action research: Andre P. et al. “Globally representative evidence on the actual and perceived support for climate action.” Nature Climate Change 2024.