Nuffield scholar finds – accessing sheep meat’s value chain key to profitability

By Patrick Francis

A Western Australia farmer, meat scientist and Nuffield Scholar Dr Kelly Manton-Pearce has identified a bright outlook for meat sheep businesses provided they are prepared to become involved post farm gate in the product value chain. Her Scholarship findings are not new, initiatives for sheep meat producers to participate in the value chain have come and gone for two decades, but their importance has reached a higher level than ever before as declining terms of trade and lower real prices for meat and wool make it more difficult to run profitable sheep businesses.

According to an ABARES 2013 broadacre farming review, specialist sheep farm businesses are on average in significant financial trouble as farm business profit has been declining for the last three years, It says the percentage of sheep farms with negative farm business profit has increased from 45% in 2010/11 to an estimated 67% in 2012/13”.

The decline in profitability reflects a decline in sheep meat prices in 2012 after a significant improvement took place between 2009 and 2012, Figure 1. In real terms (after price is adjusted for inflation) sheep meat and wool prices now are on par with 2001.

Manton-Pearce used her Nuffield Scholarship to review two aspects of the sheep meat business, firstly the opportunities for expansion in existing and emerging markets, and secondly how farmers can improve profitability by participating in the value chain rather than selling a commodity at the farm gate.

While her review of market opportunities covers well documented changes in consumer demand, her research contains interesting insights into less commonly known factors. These include her discussion around live animals versus processed meats, and how New Zealand’s reputation as a sheep meat supplier compares with that of Australia.

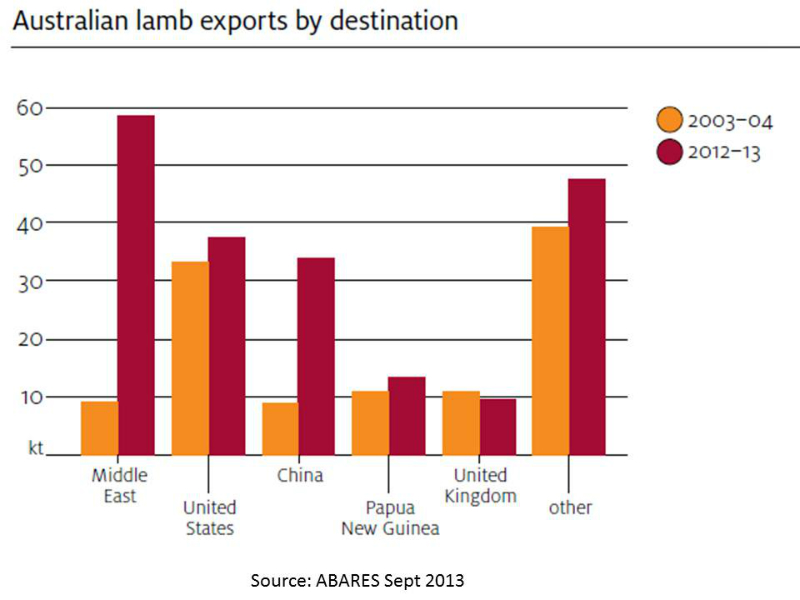

According to Manton-Pearce, emerging markets in developing countries- China, India and Middle East represent significant export opportunities for Australian lamb and sheep meat.

“We need to utilise these markets as a way of value adding the entire carcase.”

This suggests she would prefer to see a higher proportion of meat exports over live sheep exports to the Middle East and applauds MLA’s education programs over eight years that have resulted in “…50:50 sale of live versus chilled whole and boxed cuts” into the region, figure 2.

She highlights a strong prospect for value adding into the Indian market with our Merino hogget wethers. “The Indians have a taste preference for older sheep rather than lambs. This class of sheep would (traditionally) have gone on a live export boat to the Middle East. Developing a WA slaughter market specific to the Indian market is a potential avenue for a risk management strategy rather than having a total reliance on live exports.

On the other hand she accepts live exports to the Middle East as an important component of WA sheep businesses. “It was exciting to see the very strong and growing demand for live animals with a premium being paid for freshly killed meat. (I) came home feeling very positive that the live export industry will continue.”

This conviction is somewhat at odds with the value chain component of her market research. She refers to a premium being paid in the Middle East for freshly killed meat, and reports “In these (Middle East) countries consumers buy and sell on weight; the carcass is broken down and sold as smaller nondescript portions. The average whole carcase is worth $200+ (which includes the transport to the Middle East). “

She makes no mention of what the dismembered carcase value is but it would most likely be double the whole carcase value. This means the WA farmer supplying wethers with say superior carcase yield or meat eating quality or credence values (associated with environmental management and animal welfare) is not party to any premium, these are captured exclusively by processors and retailers in the Middle East.

New Zealand leads export marketing

Manton-Pearce’s second important sheepmeat market insight surrounds the comparison between New Zealand’s approach to export marketing and that of Australia. The impression given is Australia has been caught napping when it comes to facilitating sheep meat marketing. This has happened in a number of important potential markets.

She found “NZ is much further progressed than Australia in terms of trade with India. …NZ is close to signing a FTA with India. Australia has just recently managed to ‘convince’ India to start negotiating a bilateral FTA. This will take years.”

In the Chinese market “Currently (2013) China has a tariff on Australian lamb which is 15% for a bone-in product. Compare this to the NZ lamb tariff into China which is under 6% due to a free trade agreement between NZ and China, which gives NZ producers a genuine advantage over Australia meat exporters.”

“In the UK and EU there is feedback from numerous traders that the Australian product lacks consistency, unlike the NZ product. Our carcases, particularly those coming from the Eastern States are too big resulting in large cuts not desired by consumers. This market specifically wants cuts from 18-22kg carcases, hence, processors need to better target the products they send to this market and offer price incentives for producers to aim for these specifications.

“It was also pointed out that the strong relationship between the EU and NZ suppliers means that any improvements in trade to this market would result in increases in NZ trade, rather than Australian (trade).

“To conclude, NZ have long been exporting to UK/EU market and as a result the British have a natural association with NZ lamb. British and European consumers have little affinity with Australia as being a sheep producing country and we need ongoing strong marketing of Australian lamb to raise our profile as a quality meat producing country but need to balance this with whether it is more worthwhile pursuing this market or focusing on other emerging markets.

Value chain participation

The second section of her report concentrates discussion around farmers participating in the sheep meat value chain as a means to increase farm business profitability. She makes the point producing more sheep meat commodity is not the solution for profitability.

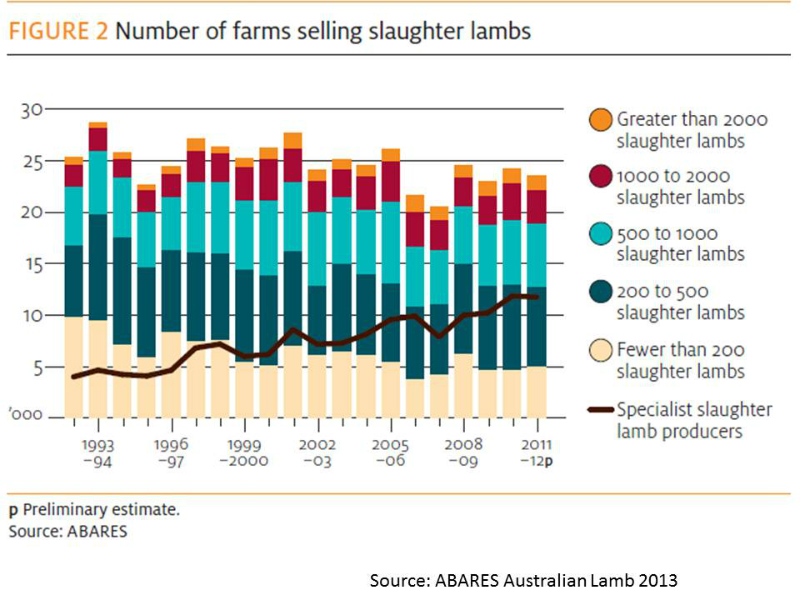

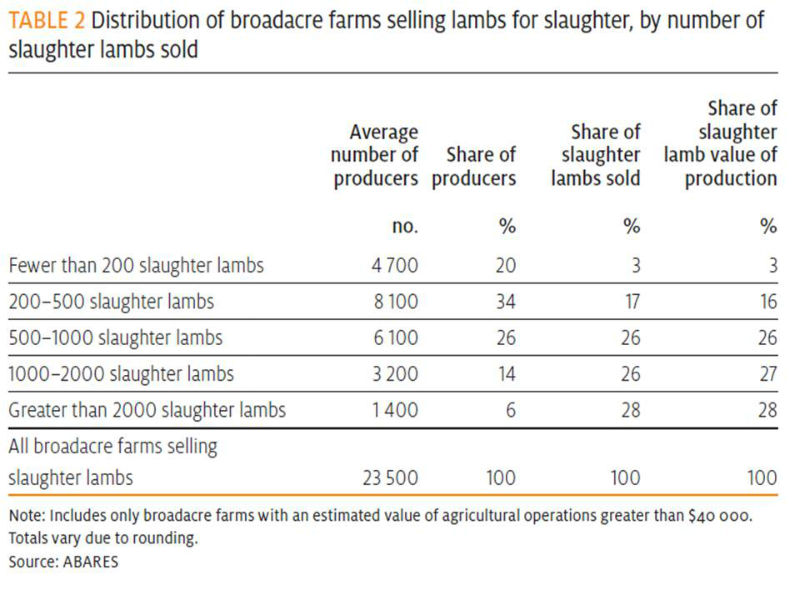

An important issue raised at the start of this discussion is to declare a reality of Australian sheep meat production – most is undertaken by farmers as a secondary rather than primary income source. Figure 3 and Table 1 reflects this situation and shows 20% of lamb producers sell 54% of slaughter lambs and collect 55% of total value.

“A high proportion of prime lamb production in Australia is based on opportunistic behaviour, where the predominant activity of the producer is an alternate farming enterprise such as cropping. The production of lambs is therefore dependent upon returns from alternate uses of land and available feed,” she says.

This has important consequences in world markets and helps explains why New Zealand’s reputation with sheep meat is so much better. For most NZ sheep farmers, sheep meat is their primary business.

“On this basis, (Australian) farmers are certainly challenged to produce a consistent and high quality product under the constraints of seasonality and feed risk and limited long term supply contracts.”

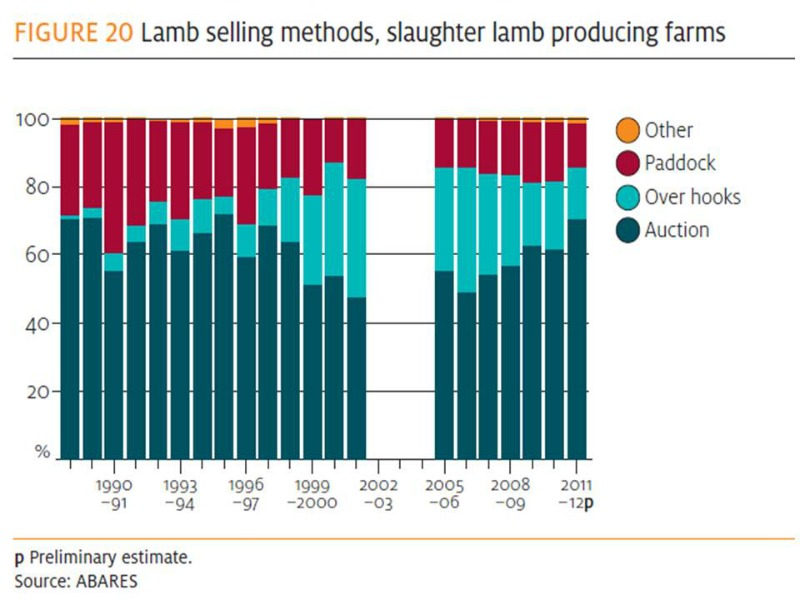

There are also a number of domestic market consequences of opportunistic sheepmeat farming which influence participation in the value chain. Firstly, National Livestock Reporting Service data, FIGURE 4, shows that since 2001 an increasing proportion of lambs and sheep are being marketed in the auction system where product quality feedback is based only on price per head or per kilogram and is clouded by daily supply and demand.

Under the production based auction system she says producers do not gain any insight of their customers and are isolated from the rest of the food chain.

“Likewise, processors lack innovative initiatives to develop the buyer-seller relationship with the producers while a low trust environment between the two often exists.”

This she contends is an unacceptable position for the sheepmeat industry. “The underlying relationships and knowledge flow among the participants needs to improve for the benefit of the whole of supply chain and for the ability of the Australian lamb and sheep industry meet future demands. The differences in drivers for producers and processors create distrust, a lack of alignment and commitment amongst participants.”

Possible solutions

Manton-Pearce has identified key components to rectify the poor relationship between sheepmeat producers and top of supply chain processors and retailers:

- Closer collaboration between sheep producers and processors should be seen as necessary to increase the competitiveness of the sheep meat supply chain, through increased trust and commitment, long term relationships and contracts.

- Currently producers are seen to be carrying out different selling behaviours and there is a desire within parts of the industry to alter or move away from certain selling practices.

- Will more intelligent longer-term supply contracts allow for a greater certainty of supply for processors and the provision of more complex incentives in terms of product attributes?

- Whilst decreasing costs and increasing efficiencies and production have been the drivers of industry competitiveness in the past, there is now a need to create more value in the end product by responding to consumer trends and behaviour. The relationship between producers and processors can have a role to play here, as some consumers desire an increased connection with the production and properties of their food.

- (All) parties must agree that their goals, although not necessarily similar, are compatible, so that each party can achieve their own objectives as well as the objectives on which the relationship has been built.

- The basis for a shared vision in the future for the Australian lamb industry must be the need to align production practices with the evolving needs and behaviours of consumers, including moderation of demand by socio-economic factors such as human health concerns and interest in animal welfare (also called credence values).

Manton-Pearce points out that Australia leads the world in ensuring lamb eating quality assurance is optimised through Meat Standards Australia grading. This program also helps provide assurances for on-farm animal welfare (low stress handling, etc) as well as meat processing to ensure optimal eating quality. But so far there is limited uptake of MSA by sheep processors and producers. It is also interesting the MSA lamb carcases receive no premium price, but MSA graded cattle carcases achieve an average 20c/kg dressed weight.

She found an important first step in developing value chain relationships between parties was open, frequent and formal communication which is personalised, frequent and high quality in terms of it being accurate, valuable and relevant.

“Those farmers in contractual relationships were demanding up-to-date information about the company position on supply specifications and often said they would continue to farm to specifications in exchange for reliable price information and proof of loyalty to farmers from the processors.”

But there is a problem with standard carcase specifications which leads to some distrust between farmers and processors. She says recent MLA findings suggest that 30-65% of Australian lambs are not meeting market specifications.

“Currently most Australian plants pay on a carcase weight and manual palpation fat score which are believed to be reflective of carcase conformation and lean meat yield and this is incorporated in the payment grid. Recent research from the Sheep CRC has indicated that manual palpitation is not repeatable within scorer but also poorly reflective of lean meat yield. The use of fat score in Australia does not provide as accurate a correlation to the yield or saleable value of the carcase. This limits not only the accuracy of different payments to growers, but also the value realized from each carcase during processing.”

This means processors need to look for tools that grade lamb carcases using consistent and accurate technology to give the best feedback to producers. (Fifteen years ago millions of dollars were invested by MLA in Viascan (video image analysis) technology to do this and some units were installed in Australian lamb processing plants. The technology is no longer used in Australia but is in New Zealand???).

Manton-Pearce suggests producer marketing groups as a structure on which to develop trust between supply chain partners and then open communication and feedback to farmers allowing them to continually adjust according to market requirements. Over the last two decade producer marketing groups have been notoriously unsuccessful in the sheep-meat sector, starting up with much fan-fare and enthusiasm but soon failing as a result of factors associated with seasonal conditions, price issues, inadequate administration and lack of communication. The increasing percentage of lambs sold in the live auction as well as the secondary nature of most prime lambs businesses contribute to the lack of interest in this approach.

In contrast, Manton-Pearce says one third of UK lamb production is sold through producer groups and the percentage is expected to grow.

“There was a growing acceptance amongst UK sheep producers that partnership arrangements are the only sustainable form of trading relationship in the long term.”

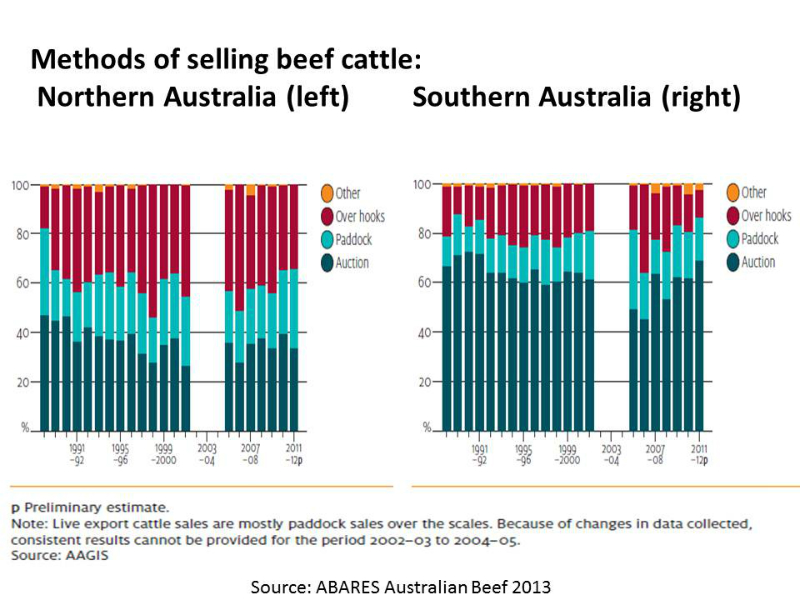

Australia’s northern beef cattle sector demonstrates a far greater involvement of producer groups and large scale individual farmers in the value chain. Both Woolworths and Coles have supplier arrangements with high levels of feedback on carcase specification targets. Two key factors differentiate beef and lamb in this regard, beef cattle are the primary business for the northern farmers and grain lot feeding provides a mechanism of retained ownership, identification of animal genetic merit and value adding. The methods of selling cattle in northern Australia versus southern Australia, figure 5, reflect these factors. Interestingly southern Australia beef cattle farmers have increased their use of live auctions for marketing stock over the last eight years, just like lamb producers, with the latest data showing in both classes of stock about the same use rate, just above 60%.

Despite the poor performance of the sheep producer groups model in Australia Manton-Pearce doesn’t dismiss their relevance and future importance. On the contrary, she supports the benefits of collaboration between producers and those further up the chain into the future.

“Any buyer-seller relationship such as a producer group should be regarded by industry as an investment,” she says.

Forward contracts

The use of forward contracts has according to Manton-Pearce become reasonably popular amongst UK and NZ sheep farmers. They were seen as the way of the future for several common reasons.

“Quality levels often demanded by contracts are increasingly becoming a prerequisite for global market access. Contracts are a way to guarantee killing space at the meat works and contract defined goals that could be worked towards. Those farmers working to contracts highlighted that they had to understand their production systems better as well as seeking earlier market indicators from the processor. Supplying to precise specifications usually requires additional monitoring skills (over and above other supply arrangements).”

Payment systems she saw working for sheepmeat in the UK and NZ were:

- Cost of production plus a margin contracts – formerly the domain of dairy and pork producers.

- Flexible forward supply contracts. Farmers are not locked in for particular days or at a particular price but must supply that number of lambs when they choose to deliver within a three month period.

- Lamb futures or basis supply contracts. These are simply a forward price deal that is linked to the physical market through the basis and market indicators. Essentially the basis is ‘worth’ about 10% of the final price and the Trade Lamb Indicator (TLI) is approximately 90% of the price, but this is also negotiable.

Value chain versus supply chain

Manton-Pearce is convinced the future for the lamb industry is for farmers to enter the lamb value chain, not simply the supply chain.

“By focussing on what consumers want, and working together to create a product, it is possible to increase the total value of the product and to optimise returns for producers. The key to success is that everyone in the supply chain makes a profit.

“China, The Middle East and India present a potentially large opportunity to value add non-premium cuts such as trim and offal. The domestic and UK/EU/US high value markets present opportunity to value add premium and non-premium cuts through refinement and packaging. The ability to produce value-added products and cuts will be integral to the lamb and sheep meat industry to maintaining value across the entire carcase, minimise wastage and missed value creation opportunities.

“Future growth of the Australian lamb and sheep meat industry therefore needs to come from increased value of production rather than increased volumes.”

Lamb’s historic commodity culture

Manton-Pearce contends the history of Australia’s sheep meat sector plus its distance from markets “… has probably resulted in an industry which has not exhibited a good appreciation of the importance and value of marketing credence attributes.

“In addition, most processors and retailers operate a very generic grading-based schedule to determine value. This approach treats our lamb product simply as a generic commodity offering limited reward to those who are attempting to tailor their production to meet market specifications, consistent quality and value adding potential.”

This has resulted in the often used Charles Massy phrase a “commodity culture” and the acceptance of a commodity price for sheep meats (see “Breaking the sheep’s back” by Charles Massy book review on this web site). Despite this she believes that because Australian farmers have historically been successful at meeting international market requirements for physical attributes of meats there is potential to increase the value of sheep meats by marketing non-physical credence values. That’s where demand and willingness to pay is growing.

“Demand appears to be growing fastest at the premium end of the market with increasing consumer interest in healthy, differentiated products and a progressively segmented lamb market. The overall goal must be to assure a high lamb eating quality at the right carcase specifications and in a highly demanded product form.

Developing value-added, retail-ready, ready-to-eat, or par-prepared food items will drive demand at the premium end of the market. As well, promoting the health benefits of lamb could also increase consumer awareness of lamb products.”

Take home message

The Australian lamb industry needs to continue to develop a strategic business approach or farmers involved may miss opportunities to retain long-term profitability and even market share.

Find out more:

Dr Kelly Manton-Pearce, Manton Farming Co, Yealering, Western Australia 08 9065 7089, pearcekelly@bigpond.com . The full report is available on the Nuffield Australia website www.nuffield.com.au