Live sheep export report unbalanced

By Patrick Francis

The Centre for International Economics’ (CIE) analysis of what cessation of the live sheep trade would do to incomes of Australia wool sheep producers must be one of the worst researched industry analyses produced in the last decade. The report “Contribution of live exports to the Australian Wool Industry” was commissioned by Australian Wool Innovations (AWI) and released in April. The fact that the wool industry and its farmer members paid for such a fundamentally flawed analysis highlights the lack of genuine interest in finding out if alternative sheepmeat pathways can boost an already depleted financial situation facing many wool sheep businesses.

Irrespective of individuals perspectives on the merits of the live sheep trade which faces questions surrounding animal welfare on ships and cruelty in overseas abattoirs, and about its economics given its product is a generic, non-value added commodity, the AWI owes it to its constituents to present balanced analysis with “what if” scenarios.

The report presents a scenario of live sheep exports being terminated overnight rather than in an organized transition where processors in Australia accommodate the live animals that would have been exported. The report doesn’t even question domestic abattoir owners about their ability to process more sheep on-shore and find suitable markets for the meat. It also fails to review developing sheepmeat markets and the relationships between Australian supply and overseas market demands.

This is particularly important for Western Australia sheep industry as approximately 90% of Australia’s live sheep exported are sourced from that state. In reality the questions surrounding phasing out live sheep exports centers directly around impacts on WA sheep farmers. Eastern states sheep farmers rely very little on the live trade and if it no longer existed would have virtually no impact on business profitability.

The greatest deception in the report when it comes to impact on WA sheep farmers profitability surrounds the ability of WA sheep abattoirs to process animals if not exported alive. Even data presented in the report doesn’t support its conclusion that “Closure of the trade will have a profound impact on WA woolgrowers and sheepmeat producers.”

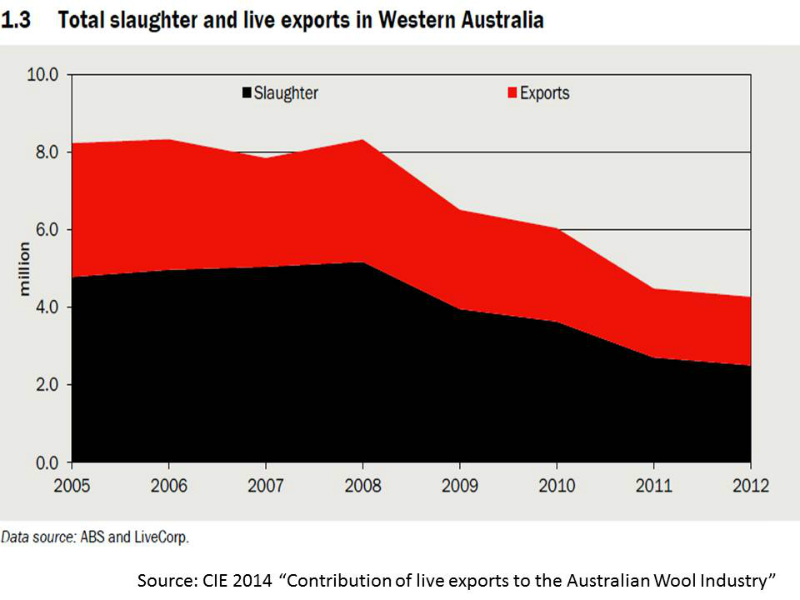

The report shows in its figure 1.3 that the total sheep slaughter in WA in 2008 was approximately 5 million head. That year approximately 3 million sheep were exported alive. By 2012 WA abattoirs slaughtered approximately 2.5 million sheep and 1.5 million were exported alive. In other words, with a dramatic drop in the WA sheep population, capacity to slaughter sheep is now underutilized to the tune of more sheep than are exported alive.

In fact the report says: “…Kingwell et al (2011) made an assessment that there was sufficient capacity in the WA processing sector to process sheep diverted from exports due to throughput levels lower than full capacity and the scope for expansion through the addition of shifts. The excess capacity was estimated to be between 1.7 and 1.8 million head per year. …. Sapere (2013) …conservatively used a total (WA) capacity estimate of 5.9 million.”

The report even notes that with current reduced slaughterings and the mining sector’s slow down more labour is available in WA to accommodate extra shifts in abattoirs.

The same lack of sheep in WA was reported in MLA’s Feedback magazine in January 2013. The cover story for the issue was about boosting sheep numbers in the high rainfall areas of the state because “5.6 million sheep and lamb annual turn-off is needed to sustain export and processor requirements, (while) 4.1 million head is the estimated 2011-12 turn-off which will not sustain processing and export.”

Even MLA says in its report “Australian sheep projections 2014” that “A significant challenge for exporters will be in securing adequate volumes of suitable sheep, given a combination of record level of sheep turnoff in 2013 and the expected strong processor demand in 2014.”

What all these additional references are saying is that in WA there should be plenty of capacity to process all the sheep that are currently exported alive from the state. As well given the state’s abattoirs found markets for over 4 million carcasses in 2008 when processed meat sheep demand was lower than it is now, there should be no issues finding profitable markets for that number or more in 2014 and beyond if live exports were phased out.

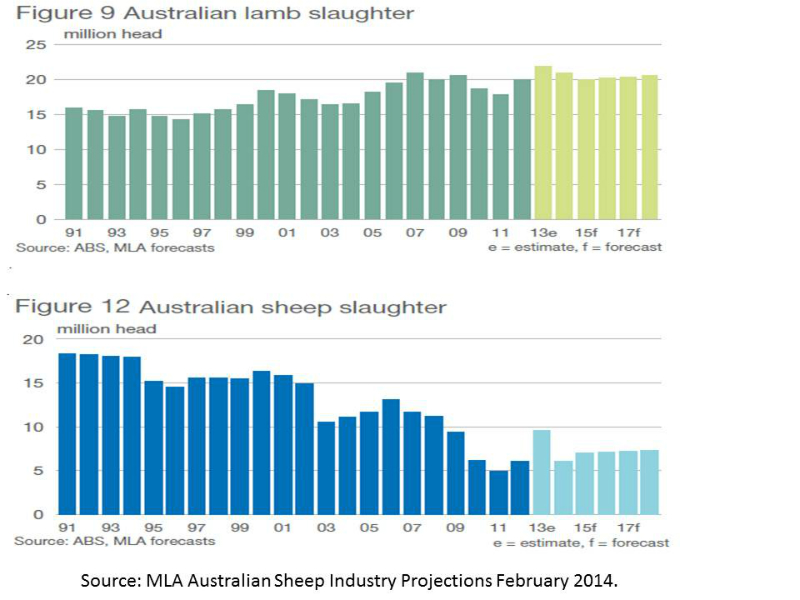

So the CIE’s conclusion that WA wool grower businesses would suffer financially doesn’t stack up in face of evidence for increasing sheepmeat demand on world markets, sheep slaughter numbers in Australia have leveled off putting a cap on production here, Figure 3, and sheepmeat production in other exporting countries in particular New Zealand has declined.

The CIE also uses some fanciful assumptions to support its argument. Firstly it ignores the ability of WA abattoirs to slaughter the annual live animal export equivalent (around 1.78 million head in 2012) and secondly suggests the retained live export animals will have to be processed in Eastern State abattoirs with a transport cost which “…could be $30 per head.”

Another curious and theoretical cost associated with the loss of live export trade is the assumption that the animals intended for export would not lose value on the domestic market because they were the better growth and size animals but their “poorer” siblings would suffer greater discounts.

“While merino types that are typically exported live will not be discounted by processors, their diversion through processing will lead to lower demand and prices paid for lower quality sheep used for mutton.”

This suggests that the Merino farmers involved do not have the management skills to finish or sell secondary animals to advantage if there is an opportunity to do so. A characteristic of the commercial livestock sector is that there are always traders present who take advantage of any animal put up for sale. Even the report recognises that it can take up to 12 months for an animal entering the saleyard market place to end up being sold to a live exporter. That’s an issue of time rather than genetic quality.

The market economic assumption the CIE makes is based on cessation of the live trade creating an oversupply of animals in WA forcing wether prices down. On the report’s own data that assumption is unfounded as there is a shortage of sheep in WA. It also fails to embrace the reality of the existing financial situation for sheep farmers which ABARES demonstrates is highly variable due to commodity price fluctuations, higher costs and seasonal conditions.

In its Farm Survey March 2013 ABARES says: “In 2011–12 a small reduction in average prices received for adult sheep and lambs resulted in a small decline in average farm receipts. Despite a reduction in average cash costs resulting mainly from reduced expenditure on sheep purchases, average farm cash income for sheep industry farms declined to an average of $87,300 per farm. In 2012–13 farm cash income for sheep industry farms is projected to decline to average $66,000 per farm.” That’s an average 25% drop in farm cash incomes in one year.

Figure 4 demonstrates how real prices for all sheep commodities are less in 2013/14 than what they were in 2001/02. While prices received impact on profitability so do numerous management factors. MLA’s Feedback January 2013 magazine story about WA’s lamb sector highlighted critical control factors that “…will have the biggest impact on whole farm profitability”. They are:

- High pasture utilization ($40 – $80/ha for a 10% increase)

- Good lamb marketing program ($50/ha for a 10% increase in value of lambs)

- High reproductive rates ($42/ha for a 10% increase in lambs produced)

- High winter pasture growth ($40/ha for a 10% increase in winter pasture growth

- Mating ewe lambs ($37/ha increase from mating ewe lambs)

All these factors (and more like financial management and exchange rate fluctuations) will impact on wool sheep profitability to some degree and highlight that isolating one factor (cessation of live sheep trade) for damaging business profitability is misleading. This doesn’t deter the CIE analysts who conclude that “overall, we expect that the Gross Value of Production of WA wool growers would be $302.4 million or 6.5% lower each year compared to 2012 terms, without the live trade.”

This conclusion is made also in the face of the report’s estimate that the loss of the live trade would turn some sheep farmers away from the industry and reduce the state’s sheep population (1.8 million head reduction on 4 million in 2012 and on 38 million in 1990). Surely such a reduction would add to the demand for sheepmeat and increase prices for lamb and mutton which is exactly what is happening in 2014 due to an increasing supply shortage both domestically and internationally.

Value adding ignored

While the CIE conclusion “… that live exports underwrite sheep prices in WA and as such should be a focus for the woolgrowers of that state” cannot be supported by the fact the state currently has underutilized processing capacity, it’s analysis completely ignores the opportunities for wool growers to value add to their sheepmeat via carcass feedback, meat quality assurance, branding and adding credence values associated with environmental management, animal welfare, and trace-back to individual farms.

Farmers participating in the value chain by adding value to commodities or retaining ownership to a point past the farm are considered by most marketing experts as the preferred method of improving farm business profits. Numerous market analyses for broadacre livestock and grain commodities have demonstrated why this is the case and the latest, by financial consultancy Deloitte, identified value-added food processing as one of 25 growth hot-spots with the biggest potential to lift Australia’s economic growth.

Further processed foods include mutton and lamb from Australian abattoirs as opposed to unprocessed live sheep. Deloitte contends on-shore processing could help catch the ‘dining boom’ in Asia and the Middle East.

“Asia values Australia’s food safety standards highly, meaning that some markets will pay a premium to have their food processed and packaged here in Australia,” it said.

According to Deloitte’s analysis Australia needs to move from producing commodity products to growing, processing and supplying more value-added premium produce.

Live sheep export is characterized by a commodity culture where farmers participation with the product ends at the farm gate. In contrast, the majority of live cattle exports especially to Indonesia are characterized by value adding and farmer participation in the value chain with joint ventures in lotfeeding and processing offshore. These have positive implications for business profitability and animal welfare, so ably demonstrated by the fact that since the 2011 Four Corners animal cruelty expose, most Australian cattle processed in Indonesia are now stunned before slaughter, a procedure not even required by ESCAS (exporter supply chain assurance system).

The CIE report highlighted the commodity culture aspect of the live sheep trade when it confirmed many sheep farmers don’t even know if the sheep they sell end up on boats.

“A common feature (of the live sheep export trade) is that wool growers will rarely be aware that they are selling to the trade.” And “the respondents (farmers) simply do not know where their sheep will be consigned (after purchase at sale yards).”

As well, the report provides scant analysis of live sheep export farm gate prices in particular the trade’s mainstay Merino wethers, to find out what trends have taken place and if adjusted for inflation whether or not the prices received could be described in its words as “… another channel to dispose of cull wethers for a good return.” This phrase demonstrates a bias or personal judgment that the live export trade sheep prices are supportive of business profitability.

While any WA wether price data is not included in the report, it is available from MLA. Figure 5 shows an interesting market price phenomenon where declining supply in WA is not met with increasing price. Given the live sheep export trade is dominated by two parties – WA farmers and Middle Eastern country buyers, it seems the later are reluctant to provide a price incentive to their “quality sheep” suppliers. A wether may have produced two wool cuts for its owner but at $70 for the live animal in 2014, the same price as 12 years ago, it is too low after adjusting for inflation to contribute to wool sheep farmers business profitability. With wool suffering the same real term price decline since 1991 it is clear that wool sheep business profits are not being maintained by selling raw commodities.

The report includes one figure showing live export trade prices for east coast sheep between January 2009 and March 2013 a period of significant lamb and mutton prices variation as shown in Figure 4. The CIE writers then make the suggestion that the introduction of ESCAS was responsible in some way for lower live export prices. As figure 3 shows between 2011 and 2013 all Australian sheepmeat prices declined and they had nothing to do with ESCAS. It is difficult to know why the authors make this link, other than they think ESCAS should not have been implemented because it is a cost to the industry. It’s another example of unimaginative thinking that is satisfied to maintain a potentially high value product as a low value commodity.

Take home message

This CIE report fails to make a case for the continuation of the live sheep trade from Australia, which in practical terms means from WA. The justifications for retaining the trade based on it being critical to retain wool growers incomes don’t add up as there is a host of industry issues involved such as:

- A significant decline in sheep number is WA means supply even for domestic processing is inadequate

- Processing capacity in WA abattoirs is underutilized compared with five years ago and has the potential to accommodate as many sheep as are available for live export

- Competitor sheepmeat exporters like New Zealand and South Africa are reducing sheepmeat production

- World demand for sheepmeat is increasing while exporter supply is declining

- Value adding to sheepmeat represents the best opportunity for Australian farmers to improve profitability once optimum production per hectare per 100 mm of rainfall has been achieved.

- Wool sheep business profitability is influenced by numerous external factors and owners management skills. No one factor is responsible for wool sheep business success.

The question that specialist wool sheep producers need to ask themselves is not the one about the future of the live sheep trade, but the one about their futures in the industry. Do they want to continue in narrow based market, commodity industry, enduring low prices and a checkered animal welfare reputation, or be part of value-added, demand driven industry recognised and appreciated by consumers around the world. The former is the live sheep export sector; the latter is the Australian processed sheep meat sector.