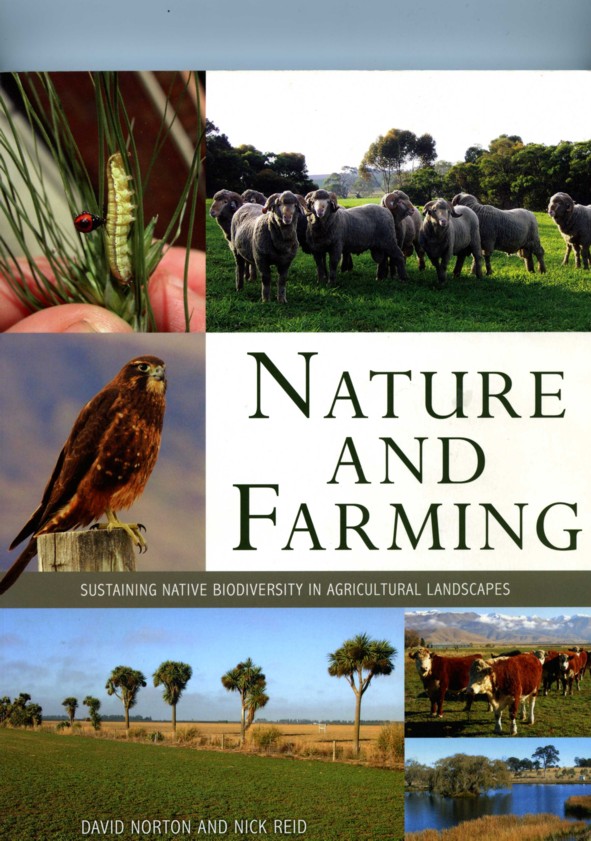

Book review: Nature and Farming

- At last an accurate review of farm biodiversity and its future

By Patrick Francis

It is refreshing to finally find a book about agricultural ecosystems in which the authors understand the reality of farming. That is, agriculture depending on its intensity, alters ecosystem functions like biodiversity, but that doesn’t mean it must be degrading or negative, it’s just different.

“Nature and Farming – sustaining native biodiversity in agricultural landscapes” by David Norton, University of Canterbury New Zealand and Nick Reid, University of New England, Armidale New South Wales presents readers with an enlightened account of how biodiversity on farms has been impacted by agriculture and how farmers can increase and manage it. The authors emphasis on farming landscapes being different rather than degrading for biodiversity will draw farmers interest rather than immediately putting them on the back-foot about their practices and turning them away from different or new ideas.

This positive approach to agriculture’s role in improving landscapes is enforced by the inclusion of a significant section of the book devoted to on-farm case studies. These are farmers who have put into practice holistic management which benefits farm productivity as well as ecosystem services like biodiversity preservation and improvement.

The book is an important contribution to agricultural literature because it provides a scientific basis for the biodiversity changes which have taken place over centuries and decades of farming and grazing across Australia and New Zealand. The authors understand how farming and biodiversity are interconnected and recognise many farmers are achieving great outcomes in this regard. It is important to note that the discussion is orientated to farmed and grazed areas in Australia’s agricultural zone, not in the pastoral zone. The authors draw a valid distinction between the two and it is one more commentators should understand when reviewing on-farm natural resources in Australia.

“Although arid and alpine rangelands used for extensive livestock production are legitimely considered agricultural land and comprise some 60% of the area of Australia and 4%of the area of New Zealand, they are by definition natural or semi-natural vegetation. Such areas have undergone little deliberate vegetation modification other than by livestock grazing, the installation of water points and perhaps some over-sowing (of pasture species).”

However, in saying the authors take a positive approach their discussion around the science of biodiversity changes associated with for example remnant patch size, and shape is sometimes academic and theoretical. It fails to give the farmer reader who has already undertaken a good deal of habitat restoration any confidence about the value of what they have done. Yet the farmers know they have had a positive impact on biodiversity. The farmer case studies demonstrate this but there is no link made by the authors to their biodiversity science coverage in chapters 4 and 5.

Apart from this there are a host of biodiversity home truths raised throughout the book. Here are some:

- Some and perhaps many farmers believe that native biodiversity is not something apart of separate from their farm that they can have, or not, as they please. They believe that biodiversity is essential to a healthy ecosystem, farm, region, country and planet.

- That a mosaic of different kinds of crop, pasture, orchard and planted woodlot provides habitat for a greater diversity of matrix (farm) species than any one kind of agricultural system. Sometimes native species of conservation significance can be more abundant in matrix habitats than in native vegetation. The matrix matters

- The likelihood for evolutionary change in biota that use or could potentially use farmland is high because agricultural habitats are dynamic and under-exploited due to their novelty and the lack of time for genetic adaptation of organisms and for species packing to have occurred. Photo crested pigeons page 66.

- Be pragmatic about your own and others’ biodiversity knowledge: question everything, especially assumptions; don’t be afraid to go against accepted wisdom when you have evidence to the contrary; base management on existing knowledge, but be cautious and learn from every action. In addition is the question of the interconnections between matrix and remnant – neither can be managed in isolation from the other.

- Debates over wildlife conservation (strategies like destocking areas) on farms miss the point that the entire agricultural estate, both the intensively and extensively managed parts have value for native biota.

- Positive outcomes for biodiversity conservation (on farm) need to be recognised.

- Technology (eg controlled traffic, conservation farming) can be both positive and negative for biodiversity.

- (Our) case studies come from working farms and it is often these farms that are the most financially successful in their region – highlighting the win-win outcomes that are possible.

- (Our) case studies (demonstrate) the power of positive farmer-driven initiatives resulting in win-win outcomes for both biodiversity and farming.

- In the Bangor Private Forest Reserve, Tasmania the number of species in plots with complete exclusion of grazing has declined significantly over time. In general grazed plots and sheep excluded plots do not vary, suggesting that native grazers effect most vegetation change. Basically macropods were the main native herbivore and accounted for more than 40% of pasture biomass removal, roughly equating to one dry sheep equivalent per hectare, the same as the sheep stocking rate.

- It is not always possible to maintain biodiversity management (eg control of weeds) when times are tough, yet the cessation of such work could see desired conservation outcomes set back many years. Furthermore, given native vegetation and endangered species regulatory controls and the lack of financial incentives to conserve native biodiversity, some (farmers) may actively eliminate (more likely ignore – author) native plants and animals in order to preempt possible opportunity costs down the track.

- The ISO system (eg ISO 14001 accreditation) is about having environmental management systems in place while certification systems are about the actual outcomes of environmental management. Put simply, the former (ISO) is about having planning procedures for environmental management in place with frequent audits verifying continuous improvement in the planning process, while the latter (certification) is about implementing plans and achieving positive outcomes for biodiversity and other values (ecosystem services like carbon sequestration, clean water) on the ground, with frequent audits to evaluate the quality of the biodiversity gains.

- Agricultural market incentives, especially comprehensive ones covering a range of environmental issues associated with farm management, are still in their infancy.

- While the overarching goal is to sustain native biodiversity unique to an area, goals need to recognise that this may be achieved through creating or sustaining novel mixes of native and exotic species rather than focusing only on reconstructing previous native ecosystems. Biodiversity goals also need to focus on ensuring the viability of native species, rather than just aiming to have a particular assemblage of species present.

- The importance of open-minded, empowered individuals and rural communities is central to our vision for a sustainable future for native biodiversity in rural landscapes. To avoid past mistakes, we need to acknowledge the failings to date of much biodiversity policy in rural areas, particularly the limitations of inflexible, top-down regulation, the consequences for native biodiversity transforming natural ecosystems into farmland, and the relationship between farmers and society in relation to heritage conservation.

- The farmer is the person on the ground year round with the best knowledge of the values of the property. Farmer engagement, cooperation and empathy, not alienation are critical to the long-term success of native biodiversity initiatives in agricultural landscapes. Realistic payment for conservation services should be considered.

- Scientists and conservationists have to recognise that farms are not national parks. Worthwhile conservation outcomes on private land can be quite different to the ways in which biodiversity conservation is achieved in protected areas.

- There is a critical need for a new breed of rural ecologist or agri-ecologist, trained in biodiversity and rural science as well as communications and extension, equally knowledgeable about farming and threatened species, and sympathetic to conservation and agricultural interests.

Despite the depth of knowledge both authors have about biodiversity in farming landscapes they fail to recognise one of its most important components, that is the soil food web as described by US soil biologist Dr Elaine Ingham. When understood and managed appropriately by farmers the soil food web represents a biodiversity wonderland unmatched by anything above the surface.

As an example CSIRO scientists Alan Richardson and Richard Simpson report in their 2011 review “Soil microorganisms mediating phosphorus availability” that “…bacteria alone may be represented by as many as 10,000 species per gram of soil…”. So the ability of farmers to positively impact the soil food web and subsequently the above ground biodiversity should not be ignored or down-played as secondary to their influence on conventional plants and animals.

Another issue the authors seem to ignore is the contribution farmers in the agricultural area have made to improving biodiversity through landcare and improved knowledge of grazing and cropping practices. Their views seem to be influenced by the long running conflict between farmers and the NSW government over its land use and native biodiversity regulations. Too often the authors refer to farmers action over “…the last 60 years…” while radical changes in management have taken place over the last 25 years. Some of their views about farmer attitudes to biodiversity and land use also seem years out of date. There is a reference to “farmers notion that productive land not used for agricultural production is a waste…”. This may have been the case 20 years ago but is not the case now as more and more farmers are prepared to allocate land for conservation purposes. Landcare primary producer awards provide excellent examples of this happening.

Their over emphasis on farming (cropping) intensification contributing to biodiversity decline is also extraordinary as evidence suggests soil health is improving (grain yield per mm rainfall increasing, inputs per tonne decreasing), and it is often accompanied by more areas not being farmed at all. As well, throughout the cropping zone, sheep numbers have declined dramatically since 1990 with many farmers no longer having a grazing enterprise. This means native vegetation in and around cropping paddocks, particularly grasses and forbs are regenerating.

What I disagree with the authors about:

- An education and awareness-raising program to raise the profile of farmland and habitat for biodiversity. And collaborative research with farmers to understand how the value of farmland for native biodiversity can be sustained. There is…limited knowledge of the options for restoration of biodiversity in farmland. Knowledge gaps mean that, in many instances, management recommendations are educated guesses based on first principles only. (Approximately $8 billion dollars have been spent in the National Landcare Program, Natural Heritage Trust, and Caring for Our Country programs over the last 25 years to create awareness and encourage action. In universities over the last 10 years, graduates in NRM related courses far exceed graduates from agricultural science courses.)

- There is limited knowledge of the options for restoration of biodiversity in farmland (Landcare Australia and DAFF claim around 60% of farmers participate in landcare so knowledge is there).

- If farm profits decline, a farmer’s ability to pursue discretionary stewardship activities and expenditure may also be reduced. (Ecological health of farmland is not separate to economic health. The two are highly correlated. Strangely, the authors agree with this later in the book when they state: “…economic viability and biodiversity are inextricably linked.)

- One of the most common options for many farmers facing the ever increasing costs of farm inputs, such as fuel, fertiliser and water is to increase productivity through management intensification. (Precision no-till cropping is reducing these inputs per tonne of grain; holistic grazing management is reducing inputs per kg of live weight per hectare per 100mm of rainfall.)

- Landcare provides the quintessential contrast to top-down intervention by governments and their bureaucracies for achieving conservation of natural resources and enhancing natural capital. (That might have been the case during the first 10 years of landcare but since then, bureaucracies set the agenda and groups comply to receive funding, if not they are unfunded.)

- Farmer and societal values and awareness are barriers to biodiversity conservation in agricultural landscapes. (For most farmers awareness is present but as society doesn’t value stewardship of ecosystem services it is paid less attention. As landcare demonstrates when funding is made available for particular environmental tasks, farmers become involved in the short term.)

“Nature and Farming” provides readers with one of the best insights into the real impact of farming on biodiversity and without mentioning them, many of the other ecosystem services. Its key points should be read and re-read by NRM bureaucrats and conservationists as at the end of the day any significant achievements made will be the responsibility of farmers taking action on their own land on a continuing basis.

“Nature and Farming” is highly recommended.

Find out more:

“Nature and Farming” by David Norton and Nick Reid is published by CSIRO Publishing and has a recommended price of $69.95; www.publish.csiro.au