Blackmore’s right to farm – a case study

Finishing Blackmore Wagyu cattle challenges pasture based farming

By Patrick Francis

Murrindindi Shire Council’s decision not to grant David Blackmore a permit for “Beef Cattle Production” on his Goulburn river flat farm near Alexandra, Victoria, has hit a raw nerve amongst farmers as well as some sections of the fine dining community, which are his Wagyu beef customers. The decision has added fuel to a growing debate about conditions imposed on farmers’ production methods, in other words their right to farm.

Blackmore has a high profile in the beef industry as a pioneer Wagyu cattle producer who successfully markets top of the range branded Wagyu beef product in Australia and overseas. It was not surprising therefore that Blackmore’s friend and celebrity chef Neil Perry initiated a change.org petition to lobby the state government to step in and alter planning laws so farmers like Blackmore have confidence in their right to farm in a farming zone.

Unfortunately Perry has allowed his heart to lead his petition story and fails to understand the complex animal husbandry and ecosystem functions associated with Blackmore’s move to finishing his Wagyu cattle on the Alexandra farm. This is demonstrated by Perry’s 18 August change.org email when he states:

“It’s outrageous that complaints on machinery noise and birds from nearby residents and hobby farmers, led to Council’s removal of David’s farming rights! Now this incredible farmer and his 1,300 cattle face being forced off his property in just 30 days.

“He’s fighting the ridiculous claim his farm is a “feedlot”. This is wrong. I have personally been on his property, many times – the cattle graze freely over green pastures and laze under red gumtrees – that comparison is absurd and damaging.”

The issues surrounding Blackmore’s dispute with the Murrindindi Shire Council are clouded by the interpretation of what constitutes a permit for “Beef cattle production”. Is Beef Cattle Production simply grazing cattle on pasture as almost all beef and dairy farmers in Victoria do, or can it involve a more intensive form of pasture grazing where cattle must be fed a supplementary diet called a Total Mixed Ration to make up for the lack of pasture quantity and or quality available to meet growth rate and meat quality requirements. Blackmore has taken the second path.

Change to finishing steers in pasture paddocks

Blackmore had been farming Wagyu cattle on his 150 ha farm on Goulburn river flats on Halls Flat Road near Alexandra since approximately 2005. The farm has some water to irrigate pastures and up until approximately 2012, breeding cows and weaners were grazed on irrigated and dryland pastures with no objections from neighbours. In fact, at least one neighbour agisted Blackmore’s weaner cattle for a year or more.

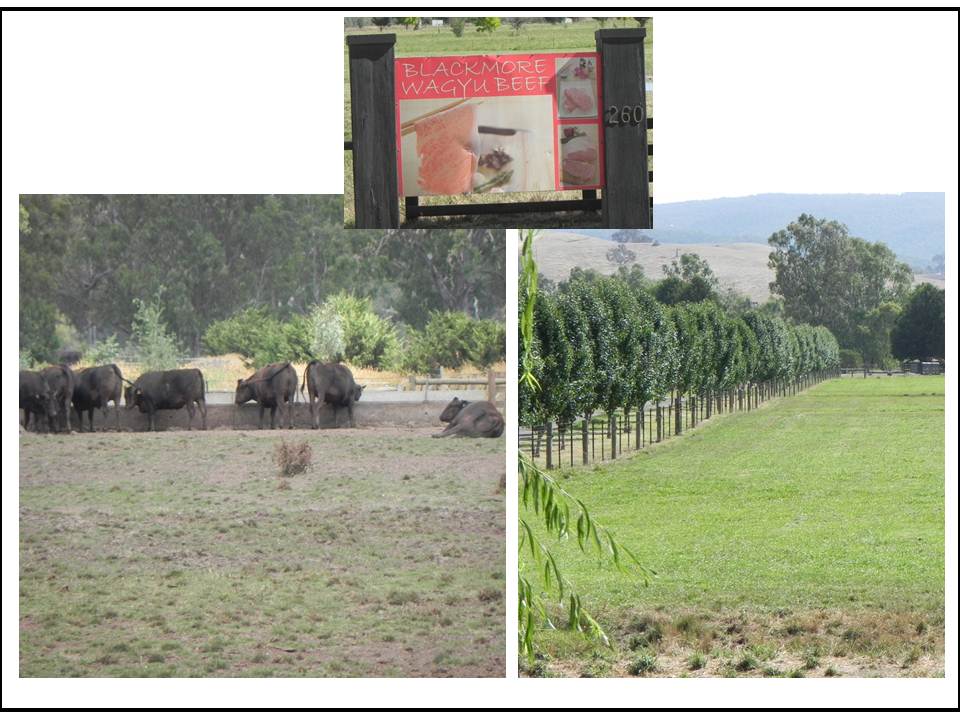

In about 2012 Blackmore added a new component of cattle production on the farm when he decided to stop finishing his Wagyu steers in a commercial feedlot, in favour of finishing them with a Total Mixed Ration fed in concrete bunks on the edges of paddocks. This means he is running two entirely different grazing systems at the one time – an irrigated pasture grazing program with rotational grazing, and a set stocked pasture grazing program with a total mixed ration supplied in the bunks, figure 1. This twin grazing methods situation is at the crux of the dispute between Blackmore and Murrindindi Council and brought about the Council’s demand for the “Beef cattle production” permit.

Figure 1: There are two paddock grazing methods in operation at the same time on the Blackmores’ Alexandra property: Left: set stocking dryland pasture with a total mixed ration fed in bunks. Right: irrigated pasture grazed on a rotational basis. Both photos were taken 30 December 2014. Photos: Patrick Francis

Blackmore’s Total Mixed Ration content is a secret but his website describes it as “…fully sustainable with natural feed commodities that are not useable for human consumption.”.

Many commercial feedlots also use such commodities in their TMRs as feed grains, silages and food processing waste materials are ideal for meeting the protein, energy and mineral requirements of steers and heifers confined in pens. And Wagyu cattle need to consume Total Mixed Rations for up to 600 days to ensure they attain the highest possible meat marbling score, to produce the most expensive beef in the world. As a comparison, most home brand MSA graded supermarket beef comes from cattle fed a TMR for a minimum of 70 days; while higher priced grain finished brands like Coles Finest and Woolworths Riverine are from cattle finished on a TMR for approximately 100 – 120 days.

While most beef cattle producers, chefs and consumers understand the value and importance of feeding a TMR to cattle in a feedlot to produce consistently high eating quality beef, some people don’t agree with lotfeeding. They equate it more with “industrial” agriculture and associate it with negative impacts on the environment and animal welfare. This sentiment has become associated with increasing consumer interest in pasture only beef cattle brands such as all certified organic beef brands, Coles “Graze”, Woolworths “Australian Grasslands”, and even Certified Angus Beef’s “Angus Pure”.

There is a strong marketing message to consumers associated with this grass only beef strategy, that is, they are eating beef from cattle that grazed for their entire life on open pasture land. For Blackmore, the pasture reared cattle image was a way of distinguishing Blackmore Wagyu from virtually all other high grade Wagyu brands where the cattle are fed a TMR for up to 600 days in feedlots.

It is interesting that even on the Australian Wagyu Association’s website, TMR feeding in feedlots is not explicitly mentioned despite the fact that it is an essential component to the breed’s success. However, one high profile Wagyu beef producer with his own paddock to plate business, Peter Cabassi, Cabassi Wagyu highlights on his website that cattle undergo “600 days of grain feeding to achieve our award winning taste”.

So Blackmore wanted the image of his beef to be associated with pastures rather than feedlots, but he still needs to feed a TMR to achieve the desired end product. In meat science terms there is no difference between the two systems, the Wagyu cattle receive the bulk of their daily intake as a high energy TMR for up to 600 days in both. Pasture alone, even if irrigated does not provide sufficient dietary energy to produce the high marbling scores required.

Blackmore admits his use of a TMR which he calls Eco-feeding®, “After weaning, our animals have access to pasture and fed our supplementary ration for 600+ days.”

So the shift in 2012 to finishing cattle on the pastures on Halls Flat Road farm meant Blackmore had to introduce facilities to store, mix and feed out a total mixed ration. It meant more fodder deliveries to the farm and more livestock trucks to transport cattle into and out of the farm. It also meant the cattle population increased from growing out weaner Wagyu cattle on irrigated and dryland pastures (called background before the animals are sent to a feedlot for finishing) to retaining them in paddocks for finishing for approximately 600 days. The Perry petition refers to 1300 animals living on the farm.

The numbers of cattle involved and Eco-feeding has created a higher level of livestock and feed transport logistics as well as on-farm food storage, processing and delivery to bunks than is associated with conventional pasture based beef cattle production. These operations all have potential to cause issues for neighbours.

Pasture’s role in diet

Despite Blackmore’s claim that “Eco-feeding® is a multi-faceted standard that includes animal welfare and husbandry, environmental management, nutrition, food safety and product integrity”, feeding a TMR in a paddock has potential to create its own environmental management issues because of the conflict created between cattle stocking rate and paddock carrying capacity. If the stocking rate exceeds carrying capacity then problems can emerge such as soil structure decline due to pugging , soil water holding capacity decline, soil erosion from water and wind, ground water contamination with manure, paddock tree deaths, and poor landscape amenity if pasture cover is lost.

Blackmore’s website says he runs 25 Wagyu animals in 2 hectare (ha) paddocks and up to 1300 animals are run on the 150 ha farm. For the 25 Wagyu steers being fed a TMR in a 2 ha paddock, the average stocking rate is around 187 dry sheep equivalents per hectare (based on one steer averaging 15 dry sheep equivalents over 600 days – dry sheep equivalents give an estimate of daily feed required based on an animal’s live weight, body maintenance requirement and growth rate requirement).

This is an extremely high stocking rate by conventional cattle grazing standards and without highly tuned grazing management supervision would quickly lead to pasture deterioration from hoof damage alone, let alone any over-grazing of plants. The care needed would be short periods of grazing (1-3 days depending on the season) followed by periods of pasture rest from grazing for 4 to 10 weeks (depending on the season and rainfall).

Dairy farmers set pasture grazing example

This is how most dairy farmers in Victoria manage their pastures which are grazed at high stocking rates without exceeding carrying capacity. To supply the extra nutrition dairy cows require to achieve high daily lactation and maintain fertility most dairy farmers feed grain and other supplements on a feed pad for a few hours each day. The feed pad is specially constructed to capture all manure runoff and to avoid any contamination of adjacent surface or ground water. After consuming their supplement the cattle are returned to pastures to graze. Without such a management strategy in place each of Blackmore’s 2 ha TMR feeding paddocks holding 25 steers becomes something like a large unsurfaced feedlot pen where the pasture is a minor, even insignificant component of the daily diet.

Blackmore says “Our eco-feeding® standard ensures we have control over the environment in which the animals are raised, their humane management and welfare. The eco-feeding® standard implements the maximum standards for animal production, far exceeding industry requirements.”

Evidence about how pasture health, soil health and surface and groundwater quality is maintained in the paddocks where the TMR is fed, is not provided on the web site. It was another concern for some neighbours when they witnessed what they considered to be pasture paddock degradation during winter and summer in the TMR feeding paddocks.

Why feedlots were built

One of the reasons why beef cattle feedlots emerged in Australia in the 1980s with their management and quality assurance processes guided by the voluntary National Feedlot Accreditation Scheme (NFAS), was to allow larger batches of cattle to be fed a TMR in an environment which optimised livestock performance, ensured high beef meat eating quality irrespective of droughts and prevented wide scale paddock and water degradation.

Before the NFAS was introduced in the mid 1980’s some farmers would feed cattle a TMR in atrocious conditions which had serious animal welfare and environmental degradation outcomes. The feedlot sector recognised it had a serious public relations image issue as a result. It introduced NFAS on a voluntary basis to prevent the threat of government regulations being imposed on the industry. The Scheme was widely adopted and within a few years around 90% of businesses were participating. The few feedlots not participating in NFAS are mostly opportunity (part-time) feedlots whose owners are unlikely to be involved in branded beef value chain.

Participation in NFAS has two issues associated with it:

- It gives the feedlot credibility as to management of livestock and feed storage, mixing and delivery logistics, quality assurances, livestock health and welfare, environmental management with particular emphasis on manure runoff, storage and distribution, and staff training.

- On the other hand it confirms the business is running animals in pens on a total mixed ration.

A feedlot is a prescribed intensive farming industry and needs local council approval to operate. Strict regulations govern their operation and siting. Most councils in Victoria and especially those in higher rainfall districts would not grant permits for feedlots on environmental and logistics grounds. The TMR method used in feedlots involves considerable cattle truck movements, grain and hay transport, and logistics for storage, mixing and feeding out in concrete bunks. For neighbours this means more noise, more dust, more traffic on local roads and more birds attracted to the grain in feed bunks. It is not surprising given these issues that most of Australia’s 900 or so feedlots are located in extensively farmed regions of the NSW Riverina and Queensland’s Darling Downs which are also source areas for the fodders used.

So despite the notoriety of Blackmore’s Wagyu beef and its attraction for tourists to the Shire, the business had created issues for itself by not having transparent livestock management, environment management and public relations plans to accommodate TMR feeding. While Blackmore claim he is not running a feedlot, he does not seem to have a credible third party monitored environmental program in place to allay fears about feeding operations on the farm. For instance he could have introduced an Environmental Best Management Practice program or even joined with an organisation such as the Australian Land Management Group which has a third party audited Certified Land Management program.

Another issue associated with Blackmore’s TMR program became apparent to neighbours and others looking over the fences along Halls Flat Road. Some paddocks where the TMR is fed which were once covered in pasture had become significantly barer, while other paddocks were lush green pasture most of the year, figure 1.

Neighbours become concerned

After three years of activities since the TMR system was introduced it was not surprising that neighbours started asking the local Council questions about how the farm was operating and was it in accordance with local planning rules?

In December 2014, Blackmore was asked by Council to apply for a permit for “Beef cattle production”. This in itself is odd as there seems to be no distinction made between extensive and intensive beef cattle production methods. Extensive livestock production in a farming zone does not require a permit. It is not clear if the Council was requiring a permit for “Beef cattle production” using the TMR method and its associated facilities and logistics, or if other issues were being questioned.

In July 2015 Blackmore was notified his permit for “Beef cattle production” had been refused. Three reasons were given for the refusal:

- “The proposal is not in accordance with Clause 13.04 Noise and Air in that it will reduce community amenity with the emission of noise from the premises and that the existing infrastructure does not have enough of a separation distance from adjoining dwellings.”

Reason 1 seems to be a de facto objection to the feed storage, mixing and distribution associated with TMR use, or in other words the Council has deemed an intensive feeding operation is in place without a permit.

- “The proposal is not in accordance with Clause 35.07 Farming Zone in that it is not compatible with adjoining and nearby land uses, in that adjoining properties are used for primarily residential purposes that will be affected in a negative manner by the proposal.”

Reason 2 is another de facto objection to TMR feeding as extensive livestock production is undertaken on adjoining properties without neighbours objecting. This reason is highly contentious as it refers to neighbours properties as being “primarily residential” which is at odds with the Farming Zone. In other words the Council has created a conflict of interest by allowing “… adjoining properties…(to be) used for primarily residential purposes”.

- The proposal is not in accordance with Clause 65.01 Decision Guidelines in that it will have a detrimental impact on the amenity of the area.”

Reason 3 is also highly contentious as no mention is made about what components of Blackmore’s “Beef cattle production” are having a detrimental impact. There are obvious concerns associated with intensive beef cattle production where cattle are fed in bunks in paddocks, but the reasons given make no distinction between that production method and extensive beef cattle production which Blackmore is practicing in many of his pasture paddocks.

By not elaborating more on the reasons for refusal to grant a permit, Murrindindi Council has cast doubts about all methods of farming in a Farming Zone. This has led to an outpouring of opinions from interested persons and farmers who are justifiably concerned about their ability to operate their farms as they see fit, within the boundaries of animal welfare and environmental laws and regulations.

The issue at the heart of the Blackmore application for a permit for “Beef cattle production” is about the intensity of production and whether or not he is conducting a feedlot which requires a separate permit. From the state of pasture in some paddocks and the presence of feed bunks in them, figure 1, it would be reasonable to conclude an intensive cattle feeding operation was in place on parts of the farm.

Could management avoid the issues?

But given its nature (that is, in paddocks rather than pens) the next question is whether or not Blackmore could conduct such a regime on a year round basis without incurring issues that caused problems for neighbours (noise, dust, road traffic, smell, birds etc) and which did not compromise ecosystem functions ( such as soil erosion, soil structure decline, manure run-off into water courses and ground water, remnant tree deaths) across the paddocks involved.

It is possible but improbable given the farm’s soil types, shallow water table, closeness to a major river, small size, number of animals run on the farm, and closeness of neighbours, that TMR finishing Wagyu cattle on pasture could be successfully undertaken in that particular location. But the Council should have given Blackmore the opportunity to prove it. At the very least it should have granted a permit for pasture based beef cattle production to continue.

Figure 2: The Murrindindi Shire Council’s decision not to grant Blackmore a permit for “Beef cattle production” is an overreaction. He should have been given an opportunity to demonstrate how an alternative management plan for the Total Mixed Ration fed cattle could work to the satisfaction of the environment and neighbours and had that reviewed after 12 months. Photo: Patrick Francis.

Its failure to do so has diverted attention away from the holistic decision making needed when deliberating on permits for intensive animal production in farming zones (see article “Right to farm livestock requires holistic decision making by farmers and councils” on this web site). It also deters farmers who have a vision for the food they produce to develop initiatives which may push existing paradigms for animal husbandry but still be viable, taking account of animal welfare and productivity, food quality and consumer appeal, and improving ecosystem functions across the farm.

The Council’s decision may also have the unintended consequence of taking the responsibility off farmers who want to push the boundaries of animal husbandry without sufficient duty of care if the Neil Perry petition and other comments such as those by the Federal Agriculture Minister Barnaby Joyce bring about change to local government planning permits.

Neil Perry says in his petition: “David’s farmed here for over a decade, producing delicious beef that I, along with many other celebrity chefs undoubtedly trust in our Wagyu dishes. This is the type of Australian agriculture that should be encouraged, not stopped.”

While Joyce said at The Australian’s Global Food Forum dinner Blackmore Wagyu was producing “a premium product in an agricultural precinct. And there shouldn’t be the argument about what they (Blackmores) are doing. If you go to that area, you know you are going to an agricultural area.’’

The Victorian government’s Minister for Planning Richard Wynne has already indicated he will review planning laws and in particular what has happened in David Blackmore’s case.

“Calling in Mr Blackmore’s case is the first step in my assessment, which I will make with advice from the planning department. I will not pre-empt the final outcome,” Wynne said.

High profile reputation or celebrity status are no substitute for delivering credible and transparent animal welfare and ecosystem function outcomes as well as machinery and transport logistics on and around farms. Unfortunately the 96,000 people who have signed the Neil Perry petition have been won over by the hype rather than the important agricultural science fundamentals that must be associated with “the right to farm”.

About the author:

Patrick Francis is an agricultural scientist who takes special interest in livestock farming methods, livestock welfare and farm ecosystem functions. He has a 44 year career involved in livestock husbandry education, intensive pig and beef cattle production, and farm management via his editorship of Australian Farm Journal, Australian Landcare Magazine and Australian Lotfeeding Magazine. He is also owns a small farm, marketing a branded pasture finished lamb and conducts grazing management and soil health workshops for farmers, landcare groups and tertiary agriculture students. For details visit www.moffittsfarm.com.au