Protecting global water catchments – China leads investments

The number of initiatives that protect and restore forests, wetlands, and other water-rich ecosystems has nearly doubled in just four years as governments urgently seek sustainable alternatives to costly industrial infrastructure, according to a new report from Forest Trends’ Ecosystem Marketplace.

“Whether you need to save water-starved China from economic ruin or protect drinking water for New York City, investing in natural resources is emerging as the most cost-efficient and effective way to secure clean water and recharge our dangerously depleted streams and aquifers,” said Michael Jenkins, Forest Trends President and CEO.

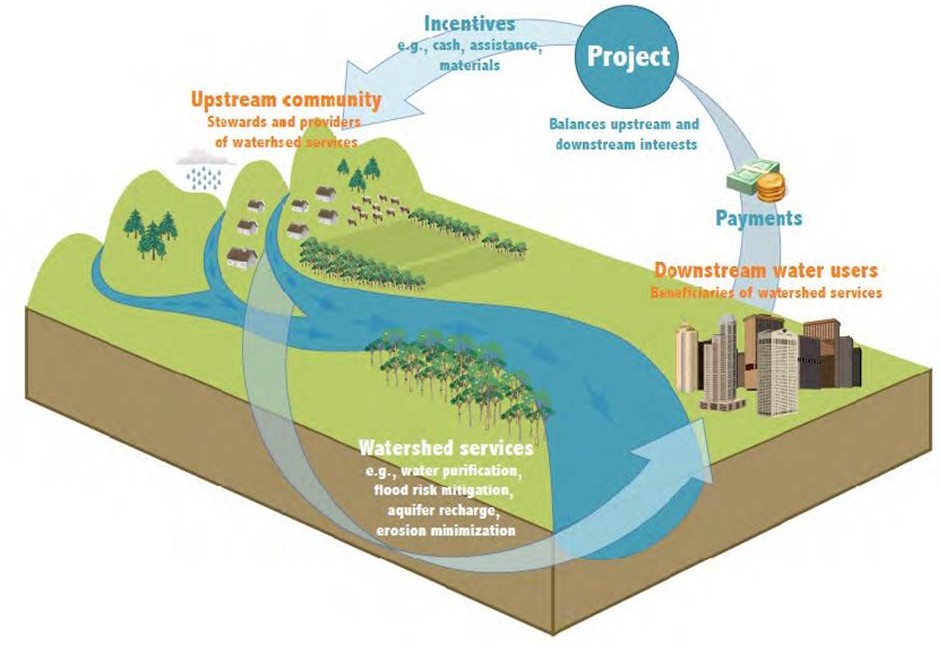

The report, State of Watershed Payments 2012 , is the second installment of the most comprehensive inventory to date of initiatives around the world that are paying individuals and communities to revive or preserve water-friendly features of the landscape. Such features include wetlands, streams, and forests that can capture, filter, and store freshwater.For some Australian land owners particularly farmers in the Port Phillip catchment around Melbourne, the report highlights how far behind world thinking the water authority Melbourne Water is operating. The Forest Trends report shows how a typical Investment in Watershed Services (IWS) project should operate, figure 1. Downstream water users – businesses and residents, contribute to a fund which provides incentives for upstream landowners such as farmers to take action to improve water shed services.

“While IWS is not the only solution, it has the potential to be a central component of watershed solutions in many parts of the world, with myriad co-benefits for local communities, biodiversity, and climate adaptation,” the report says.

Experts at Forest Trends’ Ecosystem Marketplace , which tracks a variety of programs that provide “payments for environmental services” or PES, find investments in watershed services emerging in both the developed and developing world as a “powerful new source for financing conservation”—and also a way to provide new “green” income opportunities for rural communities.

The report counts at least 205 programs—up from 103 in 2008—that in 2011 collectively generated US $8.17 billion in investments, an increase of nearly $2 billion above 2008 levels. The report also identifies a raft of new programs gearing up for launch in the next year. “The level of activity is far more intense than it was just a few years ago when we began tracking these types of investments,” Jenkins said.

For the most part, the watershed investment programs documented in the report involve relatively simple exchanges, but the return on investment can be considerable.

For example, authorities in China are providing new health insurance benefits to 108,000 residents in struggling communities that lie upstream of the bustling southern coastal city of Zhuhai in exchange for adopting land management practices that will improve drinking water for the region. The program is just one among many such efforts underway in China, which emerged in the Ecosystem Marketplace report as the world leader in using investments in watershed services to deal with water challenges. In fact, China accounts for 91 percent of the watershed investments in 2011 documented in the report.

China has the lowest amount of freshwater resources per capita of any major country in the world, according to the World Bank, and water scarcity and water pollution already cost China 2.3 percent of its gross domestic product. “Water insecurity poses probably the single biggest risk to the country’s continued economic growth today, and the government has clearly decided that its ecological investments will pay off,” the Forest Trends report states.

On the other side of the world, officials in New York City were faced with the prospect of spending billions of dollars on new water treatment infrastructure. They opted instead for a much cheaper program that compensates farmers in the Catskills for reducing pollution in the lakes and streams that provide the city with its drinking water. The effort has been credited with, among other things, keeping safe drinking water flowing from city taps throughout Hurricane Sandy and its aftermath—filtration plants and water infrastructure require electricity to function, while natural ecosystems function throughout even the longest power outages.

But China and New York City are not alone in grappling with major water-related challenges. In the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency reports that in the last five years almost every region has experienced water deficits and at least 36 states will face some type of water shortage in 2013. Ecosystem Marketplace documents 68 watershed payment programs in North America and 18 more in development that respond to these challenges. Leading the charge are Oregon, Washington state, and also Minnesota.

Meanwhile, in the developing world, 700 million people in 40 countries face water shortages. Today, one third of the World Bank’s loan portfolio involves water projects. And though investments in watershed services are growing rapidly, they are tiny compared to the estimated US $1 trillion per year that will be needed through 2025 to meet water supply and sanitation demands. Analysts at Ecosystem Marketplace note that devoting even a small fraction of these investments to “green” solutions that protect water at its source—compared to “gray” solutions like water treatment facilities—could generate huge returns by simultaneously providing water security along with a host of environmental and social benefits.

Inventorying Investments in “Natural Infrastructure”

The Ecosystem Marketplace inventory of watershed investments reveals a wide array of creative and innovative approaches around the world where, faced with major water challenges, “leaders and communities have opted to invest in our natural infrastructure and reward the people who protect it.” For example:

- In South Africa , a US $109-million investment in rooting out water-hogging invasive plants—a single eucalyptus tree can guzzle 40,000 gallons of water a year—currently employs 30,000 previously unemployed people and has returned an estimated US $50 billion worth of water-related benefits, such as vastly improved stream flow.

- In Sweden, a local water authority found it cheaper to pay for a program to establish blue mussel beds in Gullmar Fjord to filter nitrate pollution than build a new treatment facility on shore.

- In Latin America, the trend in water programs is to offer compensation other than cash for protecting water resources. In Bolivia’s Santa Cruz valley , for example, more than 500 families receive beehives, fruit plants, and wire (which is used for, among other things, fencing to keep livestock away from rivers and stream banks) in return for their water protection efforts.

- Fukuoka City in Japan has no major water supply within its boundaries, so it is supporting a water source conservation fund that pays for forest management and land acquisition in a nearby watershed that supplies the city with its drinking water.

- In Uganda , a beer brewer is paying for the protection of wetlands to retain their valuable capacity to maintain a steady and abundant supply of clean water. A similar project is in development in Zambia, funded in part by SABMiller subsidiary Zambian Breweries PLC.

- In Kenya’s Lake Naivasha basin, a consortium of large-scale horticulture operations, ranchers, and hotel owners near the lake are providing smallholder farmers with vouchers for agriculture inputs in exchange for implementing practices that can reduce farm run-off, which damages irrigation systems and harms biodiversity and landscape beauty. Farmers are using the vouchers to buy high-yield crop varieties that provide more profits as well as food for their families.

Investing in ecosystem services

“The benefits from these watershed programs extend far beyond water: they support biodiversity, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and provide income for the rural poor,” said Genevieve Bennett, lead author of the report and a research analyst with Ecosystem Marketplace .

Bennett said work is already underway to tap these synergies and make conservation even more lucrative by combining investments in watershed services with payments for other types of ecosystem services. For example, in Vietnam, tourism operators make investments in watershed conservation that are based, in part, on the estimated values of a pristine landscape for the tourism industry. In the US state of Georgia, the Carroll County government has created stream-bank mitigation credits on land that was originally acquired to protect key water source areas. And in Indonesia, watershed investments have been packaged with credits for conserving carbon stored in forested areas.

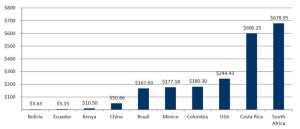

Average payments per hectare ranged considerably, as evidenced by Figure 2. Payment levels can be affected by local resources, opportunity costs, the value (perceived or otherwise) and costs of the intervention itself, transaction costs, and also project stage. For example, Working for Water, the largest program in South Africa, reported hectares newly rehabilitated from invasive plant species in 2011. Intensive restoration will likely cost much more on a per-hectare basis than annual maintenance payments thereafter, or ongoing payments for soil and water conservation measures undertaken by agricultural producers.

One disappointing finding, according to Forest Trends, was the limited participation of the private sector in paying for watershed services—despite the fact that a majority of the Global 500 companies report experiencing water-related challenges. Forest Trends identified only 53 programs that included private sector participation, the majority of which involved beverage companies. Instead, most of the programs tracked in the report are operated by NGOs or governments.

“It may be that many companies are waiting to see programs become better established,” Bennett said. “Unlike the carbon trading world, water lacks well-established tools and standards that help companies to understand and mitigate their risk, and that seems to be a major hurdle.”

Overall, Bennett and her colleagues believe the market for investments in watershed services is primed for considerable growth, particularly as economic conditions improve. They find evidence indicating that China’s “already massive investments” will increase significantly, along with investments in Latin America and the United States.

Find out more:

Anne Thiel athiel@forest-trends.org ; full report is available at www.forest-trends.org

Forest Trends’ mission is to maintain, restore, and enhance forests and connected natural ecosystems, which provide life-sustaining processes, by promoting incentives stemming from a broad range of ecosystem services and products. Specifically, Forest Trends seeks to catalyze the development of integrated carbon, water, and biodiversity incentives that deliver real conservation outcomes and benefits to local communities and other stewards of our natural resources.

Forest Trends analyzes strategic market and policy issues, catalyzes connections between producers, communities and investors, and develops new financial tools to help markets work for conservation and people. Ecosystem Marketplace, an initiative of Forest Trends, is a leading source of information on environmental markets and payments for ecosystem services. Our publicly available information sources include annual reports, quantitative market tracking, weekly articles, daily news, and news briefs designed for different payments for ecosystem services stakeholders. We believe that by providing solid and trustworthy information, we can help incentives and payments for ecosystem services become a fundamental part of our economic and environmental systems.

Caption

The report has found that farmers who take action to improve water quality also contribute to a range of other ecosystem services and for small holder farmers in developing countries to improving their socio-economic circumstances.