OECD-FAO food outlook to 2022

Australia’s productivity focus needs rethinking for farmers profitability

By Patrick Francis

While many observers of future world food production highlight major shortages emerging as a result of increased populations, farm land degradation and climate change, the lastest OECD-FAO world food outlook to 2022 shows little such concern. What stands out for the next decade is that food production in developing countries is going to increase significantly to help meet domestic demand and export countries will need to compete more strongly in their food value-added offers.

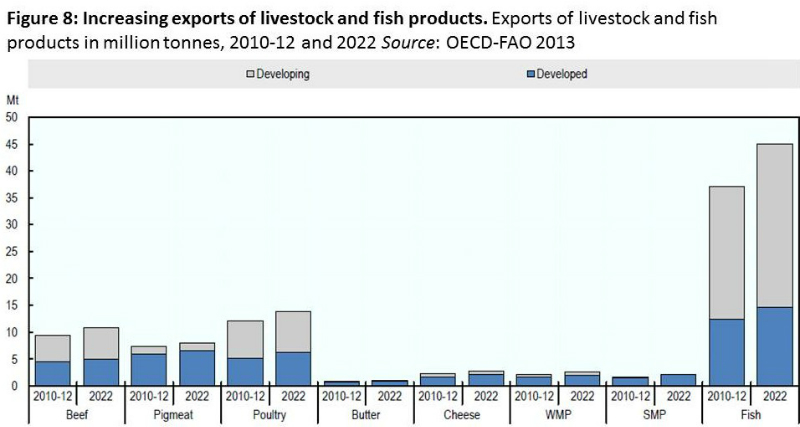

The report offers little joy for farmers in developed countries who export commodities, price increases in real terms are only expected for beef, pigment and fish. Even these real price increases (which is the price adjusted for inflation) are minor, less than 5% for the period up to 2022, figure 1.

If such predictions prove correct, then the already precarious financial position of many Australian broadacre farmers can only worsen. The actually profitability of farming is not being addressed in Australia as politicians skirt the issue by referring farmers to strategies such as increasing productivity and exporting more commodity to emerging Asian economies where a growing middle income will pay more for food. What isn’t mentioned in this scenario is that the supply chain in these Asian countries aims to capture the lions share of the consumers dollars and purchase raw commodities from Australian farmers at the lowest possible prices. In fact, the commodity export orientation is becoming more pronounced as food processors close down to relocate overseas where costs per unit of production are lower. This scenario is particularly acute for processed fruits and vegetables, with companies closing down Australian operations. Data from the Australian Food and Grocery Council shows that in 2011-12, 335 food businesses closed down or moved overseas. In stark contrast, a recent ANZ bank review of China’s food sector shows an average 225% increase in food processing and manufacturing businesses between 2001 and 2011 (from 18,000 to 41,000).

The high cost nature of domestic processing is also impacting the livestock sector and is reflected in low prices paid and escalating beef farm business debt . The situation was highlighted by Australia’s largest processor at a recent conference.

JBS Australia director John Berry said Australia’s proximity to Asia was no guarantee of a competitive edge in the market. He cited a range of barriers such as it costs 2.4 times as much to process an animal in Australia as it does in the US, and three times as much than in Brazil. For example a skilled boner in Australia cost $30 per hour, plus 40-42percent on-costs or $43 per hour, while an equivalent worker in the US costs $18 per hour.

Berry said in his company’s abattoirs electricity, gas and water costs in Australia were twice that of the US, while Australian processors now also pay $93 million in federal meat inspection and quarantine costs following a Federal Government decision to convert to full-cost recovery of those services; costs which are still funded by Government in the US and Brazil. The carbon tax had added a direct impact of $6-8/head to processing costs in Australia, costs that again did not exist in the US and Brazil.

The Australian cattle farmers price slump is not reflected in the current FAO-OECD world price data which shows beef prices being boyant.

“In terms of livestock products, prices for red meats are high at the start of the outlook period (2013) due to depleted livestock inventories and high feed and production costs. They are projected to continue at high levels for beef in the near term. Higher beef production in following years with gradual livestock inventory expansion leads to some easing in prices,” the Review says.

It subsequently raises an interesting and rarely mentioned issue about prices which farmers can control, that is, reduce supply to the market.

“All meat prices increase in the later years (2018 – 2022) of the outlook period as demand strengthens and as livestock producers moderate production growth to maintain returns.”

It is a risky strategy that could lead to greater food price chaos as producers would amplify the existing boom-bust cycle associated with second guessing prices, climate outlooks and a host of national physical and policy issues.

The highly fickle nature of commodity prices has been demonstrated in Australia over the last 12 months, where cattle prices have been similar to those received in the early 2000’s, as a result of a high A$, high cattle inventory, and poor seasonal conditions. Despite this export of beef is close to a record high. At the same time beef cattle farmer average debt levels are at a record high, and equity is declining in face of falling land prices.

Federal and state agriculture politicians are stuck on the premise of lifting productivity as the solution to on-farm profitability because it is a politically easy solution and puts the onus on back on farmers . The fact that it can ramp up farm debt and do little to improve profitability seems of little concern. A typical approach is that of Queenland’s Agriculture minister John McVeigh who recently released the state’s Agriculture Strategy. He said with increasing global population and expanding middle class in Asia, the coming decade represented an unprecedented opportunity for growth in beef and broadacre crops. The OECD-FAO report does not substantiate this claim for Australia’s two largest value export foods beef and wheat. Interestingly he cited that horticulture was an exception to the growth scenario, that sector needed to explore greater market access and higher value for what is grown. The OECD-FAO report suggests the same should also apply to beef and grains.

Meat & Livestock Australia is assisting individual beef and lamb businesses do this via Industry Collaborative Agreements (ICA) to co-fund brand awareness and transperancy amongst potential consumers. Recently OBE Organic, a beef cattle and lamb producer company which exports certified organic red meat used ICA funds to produce a series of short videos that focus on “the people, not the product”. The videos tell consumers how and where OBE products are produced, and by whom. A second series of videos is aimed at building trust in OBE’s processing methods and allay any concerns amongst muslim consumers about the Halal status of meat produced by the company.

Food consumption growth uneven

An important point made in the OECD-FAO report about the rapidly increasing per capita food consumption in developing countries, is that it is not uniform.

“Aggregate food consumption in per capita terms is projected to expand most rapidly in Eastern Europe and Central Asia where income growth is projected to be the highest. Food consumption per capita is also expected to be high in Latin America and Asia, but less so in Sub-Saharan Africa, due to wide disparity in income growth and its distribution; features which have not led to strong food consumption increases in the past.”

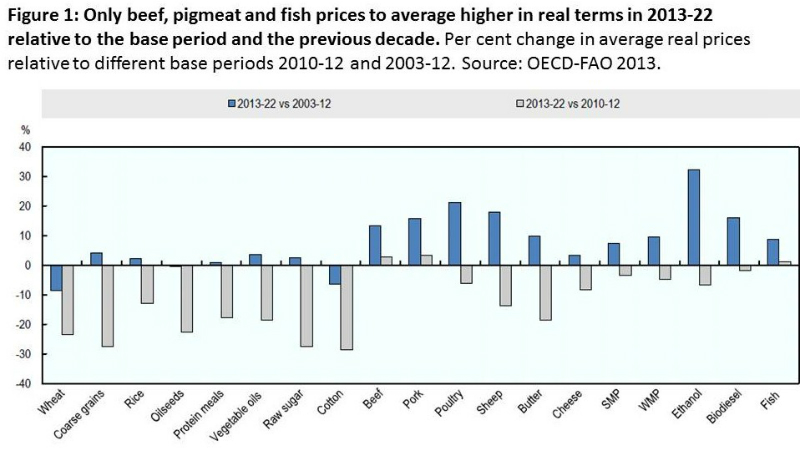

Figures 2 and 3 show projected consumption increases of crop and livestock products in OECD versus developing countries. Higher consumption in the OECD is expected to be about half the increase experienced in developing countries.

Who will grow the food?

The question rarely discussed in Australia about the future consumption pattern is who will grow the extra food required. The OECD-FAO is confident that world prices are going to be sufficiently high to encourage farmers to lift production and invest in technology, despite saying earlier that livestock farmers may have to ‘control’ production output to ensure sufficiently high prices are reaslised.

It contends food output will increase at an average of 1.5% per annum from 2013 to 2022, slightly down on the 2.1% pa growth from 2001 to 2012. This food output is faster than population growth.

The report makes the point that while land available for agriculture is becoming more limited in some countries, this is not universal and in emerging countries like Brazil and Russia more land will be farmed over the next decade. As well, the type of farming in most countries will change and intensify. For instance some pasture land will convert to cropping, while some lower value crops like cereal grains will be replaced with higher value crops like oilseeds. Both these scenarios are happening in Australia with higher rainfall cropping replacing pastures, and canola replacing some cereals.

Another factor involved is intensification of cropping, particularly double cropping in a single year. This means farmers using improved cropping methods can plant two crops a year on the same area. Statically the land area is only accounted for once, but crop production per hectare happens twice. A typical example is a winter cereal after harvesting rice. Dr Ramesh Chand, National Centre for Agricultural Economics and Policy Research, New Delhi, India told this year’s ABARES Outlook conference that by 2025 crop intensification would reach 136% in India and is a major influence on increased domestic food production. The OECD-FAO Report cites current crop intensification in China at 135%. As well as these factors the report says higher yields from improved plant genetics and agronomy will contribute to increasing output.

What is exciting and optimistic for future world food production is the countries that growth will occur in. The OECD-FAO report says that across both livestock and crops it will happen mostly in developing countries.

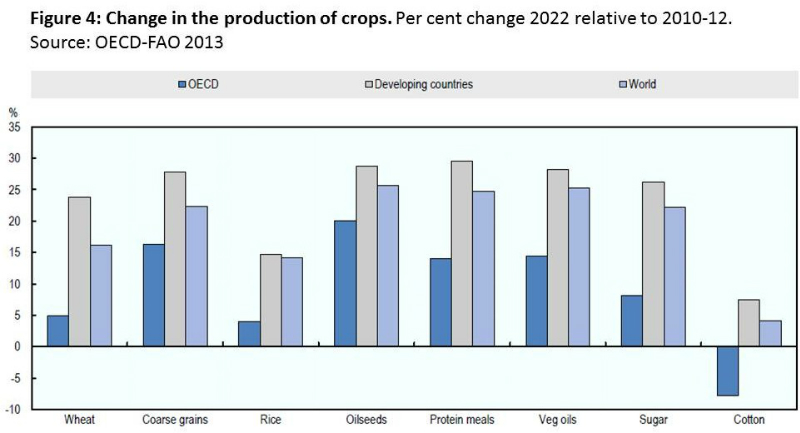

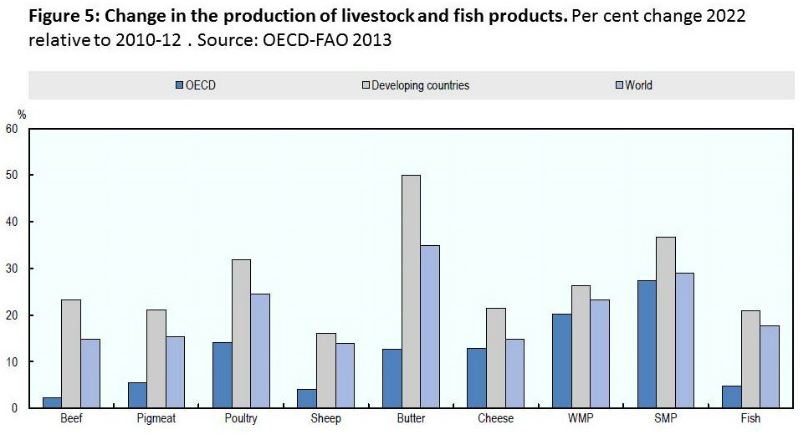

Figures 4 and 5 show changes in production of crops and livestock products in OECD and developing countries. The report says increased food production will be consumed domestically as well as exported.

These conclusions about developing countries producing more grains and meat has been recently reinforced from other sources. Dr Ramesh Chand, presented an “outlook for India’s production of different grains and meats up to 2025, table 1. Despite an increasing population and a growing middle income sector there are only two domestic production deficits indicated, for pulses and edible oils.

Table 1: India’s outlook to 2025 for domestically grown grain and meat commodities. Source: Ramesh Chand ABARES Outlook 2013.

Figures 4 and 5 and Table 1 indicate export prospects for some commodities out of OECD countries may not be as rosey as some commentators and politicians suggest. Alternatively the mix of crops or livestock may need to change to meet world demand. A classic example is demand for coarse grains. These are projected to be considerably higher than the increased demand for wheat and rice from developed countries. That’s associated with increased demand for intensive livestock production particularly pigs and poultry in developing countries, their inability to grow sufficient quantities of these grains, and with increased biofuel production in developed countries.

The Federal Coalitions recent North Australia policy release demonstrates that lack of market intelligence involved in its formation. There was no indication as to which crops could be profitably grown and marketed in Asian countries if irrigated farmland was developed.

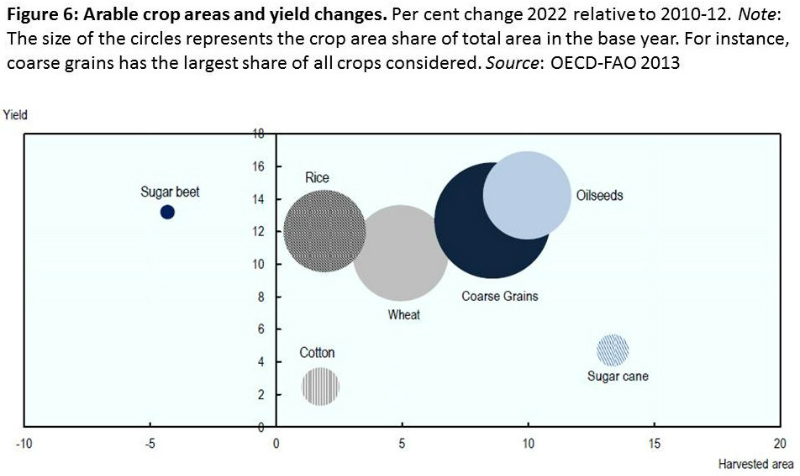

The OECD-FAO report predicts crop expansion area up to 2022 will be higher for coarse grains, 8%, than for wheat (5%) and rice (2%), figure 6.

“The additional demand for biofuel feedstocks over the projection period (mainly maize and rapeseed) is driving the large expansion of coarse grains and oilseeds in developed countries. In developing countries, the main driver is the feed demand for livestock.”

The OECD-FAO report says farming profitability in developed countries “can be expected to further slow the growth in production”. It says projected increases in energy and oil prices will add to farm input prices in these countries, but in developing countries with less intensive farming practices and pasture based dairy and meat farming these factors will not be as great a deterant to production growth. Livestock farmers in Australia and New Zealand are well placed to take greater advantage of lower cost pasture based production as well as growing middle income consumer preference for “natural” products, exemplified by the OBE Meats initiative.

The report heralds a warning about not implementing a fair level of profitability from the farm gate to the consumer

“This will be required to ensure the increasing food supplies needed by an expanding global population and to reduce upside price pressures over the long term.”

Dr Chand also emphasised the importance of achieving higher commodity prices and improving marketing methods for Indian farmers if they are to meet domestic demand over the next decade and beyond.

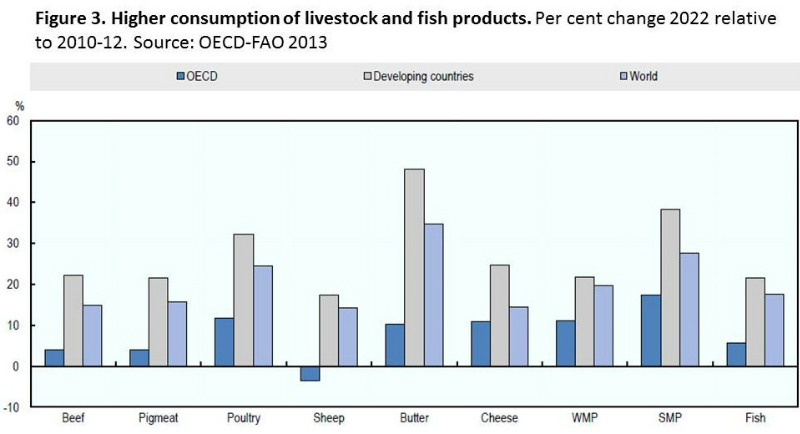

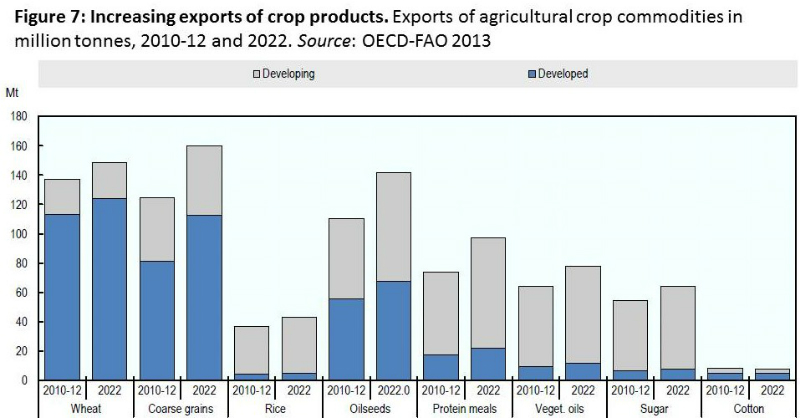

Food production growth in developing nations will be so great over the next decade, figure 7 and 8, that the report predicts these countries “…will account for the majority of exports of coarse grains, rice, oilseeds, vegetable oils, protein meals, sugar, beef, poultry meat, fish and fishmeal.”

It says South America and former Soviet Union countries are heading toward being “..major growth centres for agricultural production”. This is supported by a recent USDA Economic Research Service analysis of grain production in Russia, Kazakhstan and Ukraine. It predicts by 2021 these countries combined will export an additional 34 million tonnes of cereals per year over the annual average between 2006-1010. Around 15 million tonnes of the additional exports will be wheat, followed by corn then barley.

The OECD-FAO report says traditional developed countries exporters, Austalia, Canada, EU, New Zealand and US will remain important players in global trade for a wide range of food commodities. It suggests these countries need to have a large footprint in the faster growing trade of value added processed agricultural products. But as mentioned earlier Australia is loosing plant food value adding businesses and is struggling to remain competitive in value added meats, its orientation is heading more towards commodity marketing rather than value-added foods. Combine this with a receiving a declining proportion of the domestic consumers food spend dollar, and it is plain why farmers are being squeezed into unprofitability

However, there are some positive outlooks for specific Australian food commodities, figure 8, including:

- A general expansion of trade in dairy products is expected over the coming decade as many developing countries consume more processed milk products with westernisation of national diets. Of the main products, butter, cheese and SMP are likely to show average annual increases of about 1.7-2.1% p.a. The bulk of this growth will be satisfied by expanded exports from the United States, the European Union, New Zealand, Australia and Argentina.

- Australia and New Zealand are expected to remain the world’s largest sheep meat exporters, to supply growing import markets in the Middle East and Asia.

- World meat exports are expected to increase by around 19% by 2022, representing, an annual growth of 1.6% and considerably less than the 4.2% p.a. achieved in the previous decade. The main factor behind the decline is the expected growth of domestic meat production in the developing world, encouraging import replacement. Meat exports are expected to be led by poultry and beef shipments, Figure 8. The bulk of the exports are expected to originate from the United States, which will account for one-third of the increase of all meats exported when compared with the base period. As US beef is also projected to account for a larger share of the FMD-free Pacific market, this will affect the trade performance of its competitors in Oceania, namely Australia and New Zealand, where exports grow less rapidly. On the other hand, Oceania exports of manufacturing beef in North America are anticipated to grow.