Wildlife rescue services provide clues to native animals threats

By Elodie Camprasse and Adam Cardilini; The Conversation May 22, 2023

Introduction: In this May 2023 “The Conversation” article two academics touch lightly on the issue of the major threat to wildlife in eastern Australia, vehicle collisions. Despite the apex predator of large marsupials being vehicle drivers the article highlights how governments embrace their responsibility for wildlife welfare by financially supporting wildlife rescue organisations to assist them to take care of animals who survive collisions. It’s a case of “closing the door after the horse has bolted”. These state government departments are so politically afraid of motorist backlash at the ballot box they refuse to introduce lower maximum speed limits on roads through known wildlife concentration areas. The result based on the data available from wildlife welfare organisations, vehicle insurance claims data and hospital road trauma research is increasing wildlife road kills and injuries as states increase their populations in peri-urban districts. Patrick Francis.

Imagine coming across an injured kangaroo on the side of the road. Or a bat entangled in fruit tree netting. Would you know who to call to get help?

After a quick search, you find the number of your local wildlife rescue service and give them a call. A trained operator gathers the information they need to assess your case and coordinate rescue and rehabilitation if needed.

Figure: Left: A rescued wombat joey photo; Elodie Camprasse. Right: Too often death is outcome of vehicle collisions; photo Patrick Francis.

Across Australia, wildlife emergency response hotlines, such as Wildlife Victoria in Victoria, WIRES in New South Wales and smaller groups throughout the country, offer valuable help to wildlife and members of the public who encounter wildlife emergencies. Data from these services can also help us understand how human activities harm wildlife at a local level. And that in turn highlights what can be done to better protect wildlife.

Figure: Governments currently prefer to financially support wildlife rescue services rather than reducie the probability of wildlife being injured in the first place by lowering maximum legal speed limits in the vicinity of high wildlife populations. Photo: Patrick Francis

In newly published research, our team analysed a ten-year dataset from Wildlife Victoria, the main wildlife emergency response service in that state. The service responded to more than 30,000 cases a year, on average, between 2010 and 2019. Around 400 cases a year involved threatened species.

Human activities the greatest threat

Many such services operate on a daily basis. They collect enormous amounts of information on human and non-human threats to wildlife, particularly in urban areas.

When you call a service about an animal, a rescuer might need to attend or, if safe to do so, you might be asked to take the animal to a vet clinic free of charge for assessment. Or it might be that the animal, such as a fledgling bird on the ground, just needs to be left alone.

Confirming what studies in Australia and elsewhere have shown, our results demonstrate that human activities do the most harm to wildlife, as opposed to more natural causes such as severe weather or being preyed on by other animals. A majority of cases were reported in the Greater Melbourne area rather than the rest of the state.

As might be expected, common species accounted for most cases. Eastern grey kangaroos, ringtail and brushtail possums and magpies were the most commonly reported species.

Of 443 identified species reported to the service, 81 were listed as threatened. The majority of cases involving threatened species (on the Fauna and Flora Guarantee Act 1988 Threatened List) concerned grey-headed flying foxes.

Generally, the main causes for concern were collisions with vehicles, animals found in an abnormal location (an unnatural habitat where they did not belong) or in buildings, and attacks by cats or dogs.

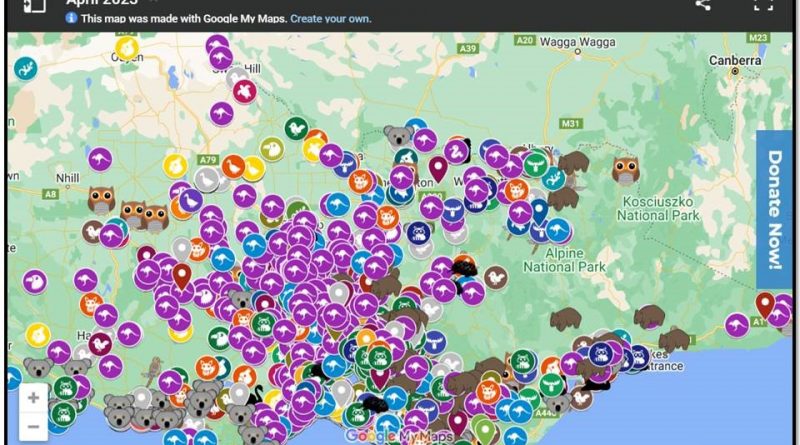

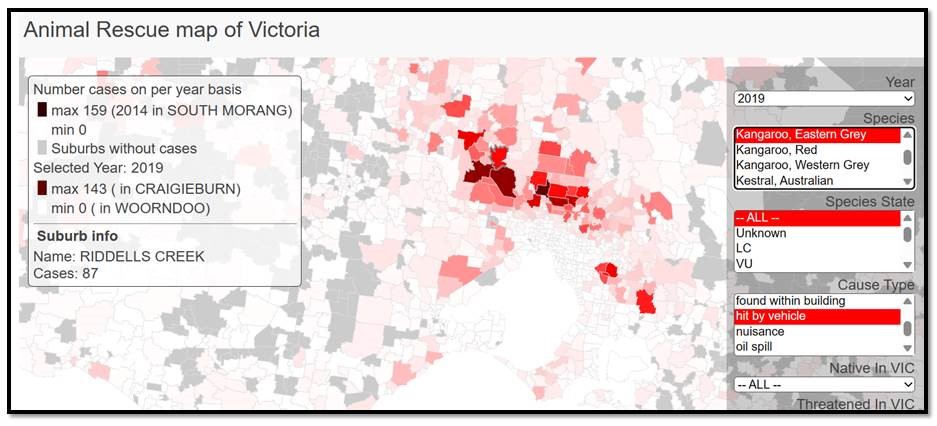

Figure: Analysis of the Wildlife Victoria Animal Rescue data shows that wildlife hit by vehicles is the major cause of injuries. The concentration of collision injuries is north of Melbourne in peri-urban shires where the default maximum speed limit on minor rural roads is 100km per hour. Source Wildlife Victoria Wildlife Victoria – Historical Data

Some species were disproportionately impacted by some threats rather than others and in some locations. For example, kangaroos and koalas were more likely to be victims of vehicle collisions outside Greater Melbourne. In contrast, ringtail possums were more likely to be attacked by cats within the metropolitan area.

Flying foxes were more frequently reported within Greater Melbourne. The main cause of concern was entanglements in nets such as fruit tree netting. The data thus confirmed the danger these nets present.

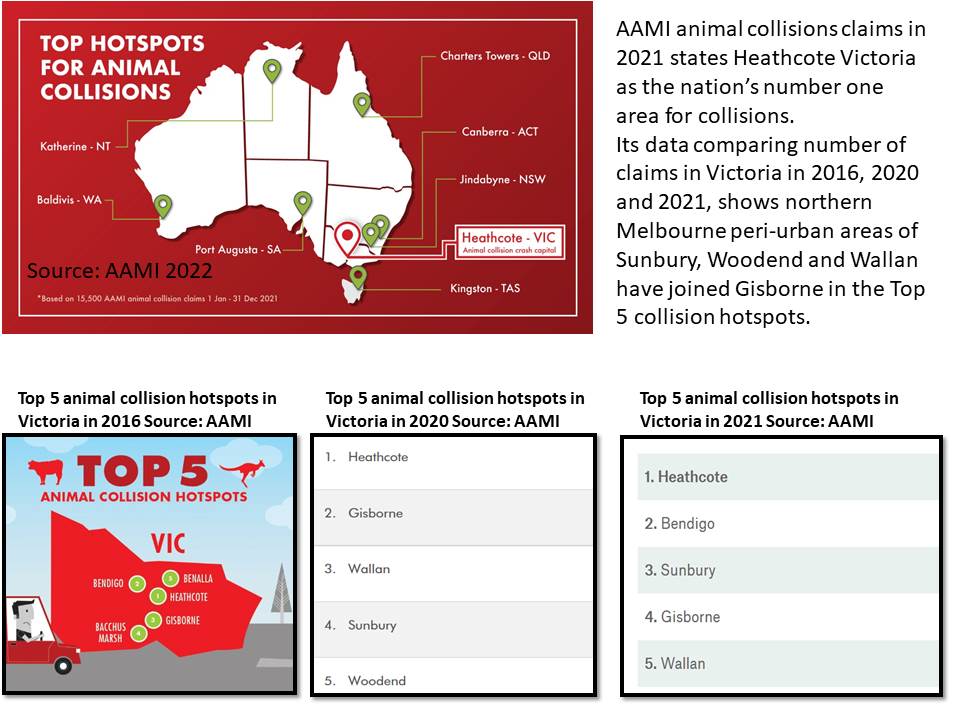

Figure: AAMI insurance company animal collision data aligns closely with wildlife vehicle collision data generated by Wildlife Victoria, with most collision hot spots in peri-urban north central Victoria. The data also shows collisions with kangaroos accounting for around 83% of total collisions in the 12 months to March 2019. Source: AAMI.

Services struggle with demand

Worryingly, Wildlife Victoria recorded a 2.5-fold increase in reported cases from 2010 to 2019.

However, such services are often under-resourced. While the number of cases increased, the number of volunteers able to respond to cases did not. This means a lower proportion of all cases can receive the support they need.

Using data from services such as Wildlife Victoria can help us understand service-demand gaps and where resources would be best allocated to fill these gaps.

We also showed such services provide invaluable education to the community. Around one in five calls resulted in education, rather than requiring an emergency response.

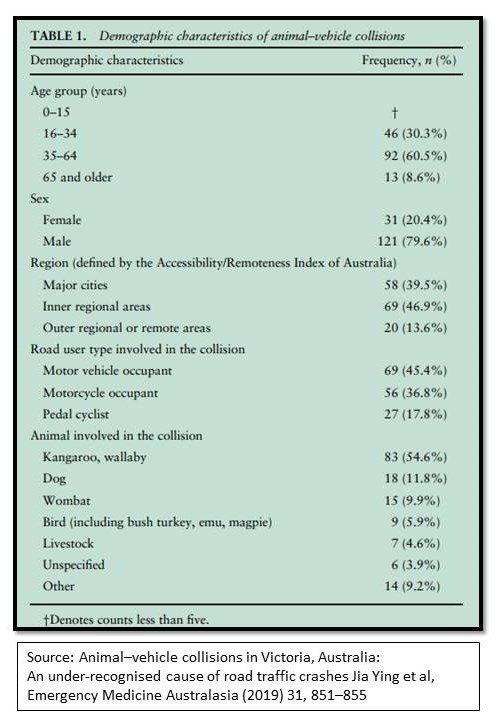

Table: Medical research into road accident injuries and fatalities is uncovering more data about the human impact of wildlife vehicle collisions. This Victorian research demonstrates that wildlife is the most frequent animal involved in collisions.

Databases are a largely untapped

Wildlife emergency response services have a wealth of data that describe the species-specific and location-specific threats wildlife face. Local wildlife managers and organisations interested in protecting wildlife from common threats before they occur could use this data to understand what they can do to achieve this.

For example, the data can help pinpoint where measures such as educating the community on responsible pet ownership, banning the sale of dangerous netting or wire and reducing speed limits would be effective depending on the wildlife affected in specific areas.

The data could also help monitor the success of new laws, campaigns and measures to protect wildlife. For example, researchers in Queensland have used data from their local wildlife rescue services to quantify the reduction in koala deaths from car strikes and dog attacks following a campaign to raise awareness of threats to koalas. This source of information is invaluable because such data can be hard and costly for ecologists and conservationists to collect.

Find out more:

Elodie Camprasse is Research fellow in spider crab ecology, Deakin University

Adam Cardilini is Lecturer, Environmental Science, School of Life and Environmental Science, Faculty of Science, Engineering and Built Environment, Deakin University

Environment Victoria: Wildlife Victoria – Historical Data

“Animal–vehicle collisions in Victoria, Australia: An under-recognised cause of road traffic crashes” by Jia Ying Ang et al, Emergency Medicine Australasia (2019) 31, 851–855