Lambs to Survive and Thrive

By Jason Trompf, J.T. Agri-Source

Introduction by Patrick Francis

Jason Trompf has collated what in my opinion is one of the best guides to successful sheep breeding and lambing. In essence he has put together a scientific description of what is simply the age old art of “shepherding”. Over recent decades the push for economies of scale by running larger flocks have not included two key ingredients shepherding and healthy pasture ecosystems. Even Trompf seems to have limited appreciation of the connectivity between ewe lifetime reproductive rate, lamb survival, sheep health and farm ecosystem services. This is demonstrated by the discussion around improving twin lamb survival by increasing pasture on offer from 500 kg green dry matter per hectare to 1500 kg DM/ha and dismissing even higher levels of feed on offer as “little value”.

Firstly, 500 kg/ha is an abominable figure for any pasture ecosystem let alone one on which sheep are lambing. Secondly 1500kg DM/ha should be an end point for grazing pasture not a starting point. Maintenance of pasture ecosystem health including soil health in a variable climate demands a minimum 1500 kg DM/ha year round. Lamb welfare and ecosystem health will benefit from pasture feed on offer starting at 3000 – 4000 kg DM per ha. Implications are not just protection from wind chill, ensuring ewes remain in the birthing area for more than six hours, and excellent nutrition, such a pasture means each mouthful of pasture is worm larvae free, the carbon stored in pasture dry matter helps the farm become a net carbon sink, and the biodiversity protected in the pasture ensure a diverse above and below ground food web.

In this edited article written by Trompf for Lambex 2014 in Adelaide, the author’s perspectives around shepherding are based on quantitative analysis, but there are aspects of this skill that are highly qualitative based around ability to read animal behaviour and develop a low stress relationship between the sheep. A New Zealand researcher has introduced the concept of ewe Maternal Behaviour Scores which is in effect a score to show the relationship between the ewe and the shepherd. A high score is associated with high lamb survival, which is what you expect when shepherding skills are optimum. The success of lamb as a high value meat in demand from consumers will be increasingly connected to farmers demonstrated skills at shepherding to ensure welfare in conjunction with producing ecosystems services across the entire farm land they are responsible for.

I disagree with Trompf’s “next steps” conclusion that the sheep industry needs to actively convince recalcitrant farmers that shepherding is important and engage with them to come on-board. All of the strategies around pregnancy testing, ewe nutrition and providing shelter have been known for decades and have been largely ignored as evidenced by lack of change in lamb survival rates. . Spending more on recalcitrant is unikely to change adoption of better management. What is likely to be more effective is promoting ethically produced sheep meat brands to consumers, creating greater demand and higher prices for those farmers delivering it.

Introduction

The on-farm value of sheep meat and wool produced in Australia exceeds $5B pa nationally with strong prospects, particularly for lamb, in both domestic and export markets. However, the continuity of lamb supply is under threat from declining flock numbers, and to improve lamb supply requires a breeding ewe-replacement strategy and continued improvements in reproduction rates at the farm level.

Projected market demand for lamb can only be met by radical increases in the carcase weight of lambs and a 10% lift in reproduction rate by 2015 (Palmer 2010). However according to Barnett (2007) there had been little evidence of improved reproduction efficiency over most of the past 20 years, with the number of lambs weaned per ewe remaining relatively stable at around 80%.

The main limitation to Australian sheep flocks improving reproduction rates is the degree of reproductive wastage from mid-pregnancy to weaning. More specifically the majority of this wastage (typically >80%) is occurring within 3 days of birth (Brien et al. 2009), known as neonatal lamb survival. It is estimated that over 10 million lambs perish in this period from birth in Australia each year (Trompf et al. 2012), however with implementation of best practice for ewe nutrition and management during pregnancy and lambing this wastage can be at least halved (www.lifetimewool.com.au).

However lamb survival is a unique challenge that not only poses a significant constraint to production that impacts directly on the ability to sustain turn-off rates while simultaneously trying to rebuild flock numbers but also is a looming welfare issue for the industry. The difference between lamb survival and many other challenges confronting sheep producers is there are actionable solutions to apply on-farm that are well researched and currently available (www. lifetimewool.com.au), and in addition recent economic analysis has shown that improving lamb survival can contribute to improvements in whole-farm profitability (Young et al. 2014).

An animal ethics issue

The failure of ewes to rear lambs also has implications for the Australian sheep industry from an ethical view point. The Victorian DEPI Sentinel Flock Project, running from 2009 to 2012, reported a loss of over 25% of neonatal lambs at birth. However, in addition to this abhorrent wastage the study found that two-thirds of the lambs died due to inadequate nutrition and miss-mothering and a further 17% of the lambs died due to dystocia, caused primarily by excess and imbalanced nutrition in late pregnancy and throughout lambing.

The challenge is to effectively and efficiently enable the everyday sheep producer to adopt strategies that mitigate these causes of loss and in the process demonstrate continuous improvement in the well-being of our national flock.

At an industry level the cost of lamb survival is profound, estimated to be in the order of $700m in potential revenue lost per year (Young et al. 2014). In addition, reproductive efficiency is also significantly influenced by breeding ewe and weaner mortalities. Industry estimates of annual ewe deaths rates are commonly 6% or more, and over 8% in weaners (DEPI Senitinel Flock 2012; Trompf et al. 2012). In fact weaner mortalities are estimated to cost the industry in excess of $75.8M annually (Campbell et al., 2009; Sheep CRC, 2010).

Despite the economic significance of reproduction, the related production and welfare issues, and well researched solutions, adoption of management strategies to address the loss of lambs, ewes and weaners remains limited (Curnow et al. 2011). For example only 17% of Australia’s breeding ewe flock are pregnancy scanned for multiples annually (Curnow et al. 2011), yet this practice is a critical part of best practice reproductive and nutritional management.

Interestingly Barnett (2007) reported that the New Zealand sheep flock, which has widespread adoption of pregnancy scanning for multiples (>85%), had improved reproduction rates by 30 percent over the same period Australia’s had remained unchanged.

This presentation will focus on the elements of ‘lambs alive- do the five’ that will deliver the outcomes required by;

(i) building a measure to manage philosophy in the custodians of our flock,

(ii) bred well- breeding a sheep that has the environmental fitness to be productive in our highly variable Australian environment,

(iii) fed well- feeding the breeding ewe appropriately for their reproductive status,

(iv) manage well- managing the ewe during lambing to enhance bonding, protection and survival and

(v) adapt well- having strategies in place that enable sheep systems to adapt to climatic variability.

In addition, the industry mission is to provide supportive pathways for change, listen to and engage with the broader public on the ethics of production, and drive product demand so that both our meat and wool industries can ‘survive and thrive’.

Economics of improving lamb survival

At an industry level the cost of lamb survival is profound. Recent economic analysis showed that the value of an extra lamb surviving birth in a pure Merino system to be worth $62 and $85 in a meat system (Young et al. 2014). Given that over 10m lambs perish at lambing this equates to over $700m in potential revenue lost per year.

Increasing conception is less valuable than increasing survival because improving conception leads to a higher proportion of twins and twin lambs have a lower survival rate. At current twin survival rates a 10% increase in scanning may only lead to as little as 2.5% increase in weaning rate. As a result the value of an extra lamb through improved conception in a Merino system, at twin survival rates of 50% is just $22 (Young et al. 2014). It is not until twin survival rates increase to 60% and beyond that increasing conception becomes viable and leads to notable increases in whole farm profit.

The value of increasing reproductive rate depends on the sheep system operating. The earlier the turn-off of wethers in a self-replacing Merino system the greater the increase in whole farm profit from improving reproductive rate.

The value of increasing reproductive rate is even higher for the meat systems ($74/extra lamb) than the pure Merino selling wethers at 17 months ($52/extra lamb). This is predominantly due to the higher sale value of the lambs and for maternal flocks the higher sale value of surplus young ewes (Young et al. 2014).

The findings of the economic analysis conducted by Young et al. (2014) is supported by a recent benchmarking analysis by Icon Ag and Agrarian Management (2014) highlighted the distinguishing features among the top 25% of businesses based on sheep gross margin among 80 mixed enterprises (Herbert and Ritchie 2014).

The key points of difference in the higher performing farms include:

• Higher stocking rate (+7%),

• Higher lambing percentage (+8%),

• More lambs per hectare (+15%), and

• Higher price for sale sheep (+10%).

These differences resulted in a higher gross margin per DSE (+31%) and per hectare (+40%).

The main advantage the top performers have is a significantly higher livestock trading profit. This accounts for 78% of the difference in gross margin per DSE between the two groups. By comparison there is significantly less variation between producers in wool income. This higher level of variation indicates that the livestock trading profit is more sensitive to management and requires a greater level of attention to do well, particularly in varying seasonal conditions.

Clearly, these producers are consistently making better decisions and less mistakes within the reproduction and selling activities of their enterprise (Herbert and Ritchie 2014).

Measure to manage – quantifying lamb survival rates and the causes of lamb loss

Given the impact of lambs produced per hectare on profitability and the sensitivity of key components of this to management (namely lambing percentage) a core challenge for the industry is how to effectively instil a measure to manage culture among sheep producers. This culture is critical to best practice reproductive and welfare management that delivers more productive, profitable and ethical outcomes.

Central to this culture is the use of enabling technologies such as pregnancy scanning and feed budgeting. Given that currently less than 10% of sheep producers know the true extent of their lamb loss and even fewer can conduct an energy budget of their ewes (Trompf et al. 2011), a massive change in producer and influencer culture is required.

Due to the fact that the majority of sheep producers don’t pregnancy test for multiples (twins, singles and dries) it is difficult to get an accurate estimate of lamb survival on an industry wide basis. However, referring to common pregnancy scanning results versus common marking rates, highlights that lamb survival in both merino and crossbred flocks requires attention, with;

• merino flocks regularly pregnancy scan at 120-140% lambs to ewes joined, yet most flocks mark only 70-85% lambs to ewes joined,

• first cross ewes regularly pregnancy scan 130-160% to ewes joined, yet most flocks mark only 100-125% lambs to ewes joined,

• consistently more than one in four lambs (ranging from 10-45%) do not survive from mid pregnancy to lamb marking.

The loss of lambs around the time of lambing is expensive, due to;

• ewes having been managed for reproduction, yet don’t produce any return via lambs,

• a 20% reduction in ewe productivity (primarily reduced fleece weight) associated with lambing and lactation, about half of which is due to pregnancy and the other half is due to lactation, and

• the opportunity cost associated with wasting feed resources on these ewes that otherwise could have utilized by more productive ewes.

Target lamb survival rates that have been found to be achievable under best practice, are;

• 92% for merino single lambs (92 lambs marked/100 Merino ewes scanned ‘single’),

• 75% for merino twin lambs (150 lambs marked/100 Merino ewes scanned ‘twin’), and

• 95% for crossbred single lambs and 85% for crossbred twin lambs.

First 48 hours critical

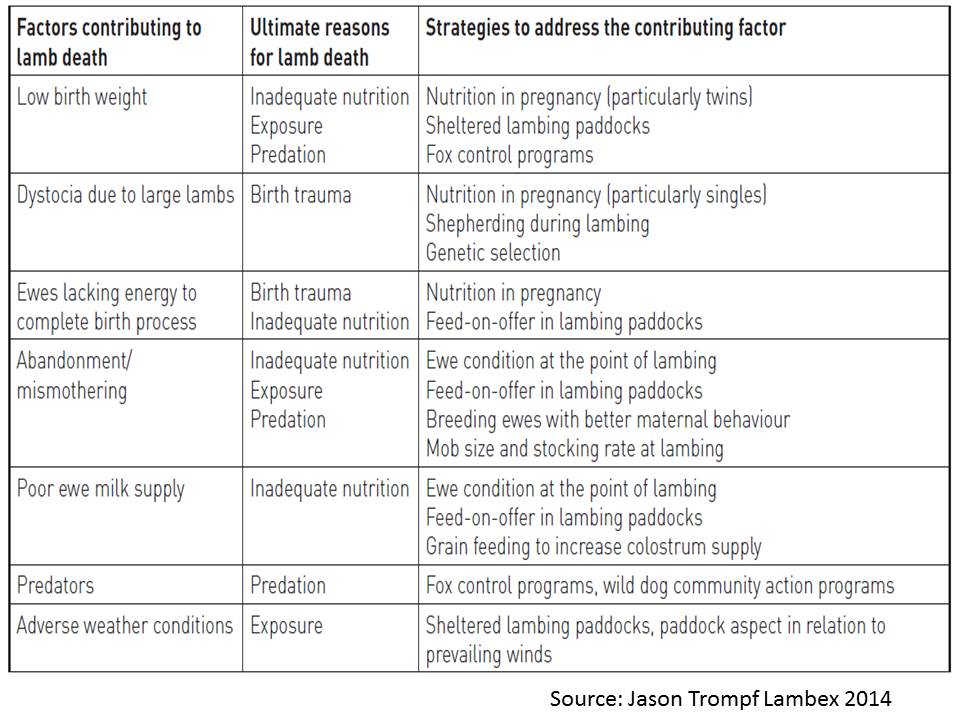

The first 48 hours of a lamb’s life are critical. Around 80% of lamb mortality that occurs between birth and weaning occurs within this period. The factors that contribute to lamb deaths and the ultimate reasons for death are summarized in Table 1, along with the suggested strategies to address these factors.

Table 1. Lamb deaths- contributing factors, ultimate reasons for death and potential strategies to improve survival

Ewe nutrition during pregnancy

Ewe nutrition during pregnancy and at the point of lambing is without doubt the most important issue affecting lamb survival. This is because the rate of survival for single and twin born lambs is mostly explained by difference in birthweight and ewe condition score (CS) at lambing. Ewe nutrition directly affects birth weight, milk supply, the process of ewe/lamb bonding, lamb growth after birth and ewe mortality.

Lamb birth-weight is determined by ewe nutrition both in early pregnancy (during placental development) and in the last 50 days of pregnancy, which is a period of rapid foetal growth. Ewe nutrition during late-pregnancy has a greater impact on lamb birth-weight (± 0.4 to 0.5 kg) than nutrition during early pregnancy (± 0.3 to 0.4 kg). The optimum birthweight for maximum lamb survival is between 4.5 and 5.5 kg for single and twin born merino lambs.

Survival decreases sharply when lamb birth-weight drops below 4.0 kg. Single born Merino lambs typically weigh about 5 kg and twin born lambs typically weigh about 4 kg. A 0.5 kg decrease in birth-weight from the average has little effect on the survival of single lambs, but can decrease the survival of twin born lambs by 15 to 20%. Lamb survival is also influenced by the amount of feed on offer and weather conditions (chill index) at lambing. The negative impacts of reducing feed on offer or increasing chill index at lambing on survival are about twice the size for twin than single born lambs. The effects of low feed on offer and high chill index on lamb survival are also additive.

Higher levels of feed on offer at the time of lambing remove the temptation of the ewe to move away from the birth site. Ideally the ewe and lamb should remain at the birth site for at least 6 hours because it can take this long before a ewe commits her lamb(s) to memory. Increasing feed on offer at lambing from 500 to 1500 kg DM/ha increases the survival and twin born lambs by 15 to 20% regardless of birth weight. Further gains in survival are small (<5%) when there is > 1500 kg DM/ha.

New-born lambs are susceptible to cold stress, which increases their risk of death. Lambs born during poor weather conditions maintain their body temperature by metabolizing brown fat (energy reserves), shivering and drinking milk. However, these energy reserves can be quickly depleted and the risk of heat loss and cold stress depends on temperature, wind and rain. These factors can be combined to estimate ‘Chill Index’, and once this index exceeds 1000 kJ/m2/h the risk of lamb mortality increases rapidly.

Reducing the average chill index at lambing from 1050 to 950 kg kJ/m2/hr increases the survival and twin born lambs by about 15 to 20% regardless of birth weight. Shelter to reduce wind speed can reduce chill index by 50 to 100 kJ/m2/ hr and therefore substantially increase the survival of twin-born lambs. It is often not possible to lamb all ewes down in sheltered paddocks so it is a matter of allocating the most vulnerable flocks to the most protected paddocks.

According to Geenty (1997) low birth weight lambs are more prone to die due to inadequate nutrition and exposure because they;

• are generally weaker and less vigorous at birth than larger lambs,

• have a larger surface area per unit of body weight, making them more susceptible to cold,

• have lower reserves of body fat, which reduces their energy levels and resistance to cold climatic conditions, and often have reduced suckling reflex.

To optimize lamb survival a range of factors need to be considered. The rate of survival of twin born lambs especially is related to their birth-weight, but survival of both singles and twins is also affected by feed on offer and weather conditions at lambing. Poor ewe nutrition during pregnancy and low condition score (CS) at lambing also has a detrimental effect on maternal behaviour and lamb behaviour that contribute to increased mortality.

Lambed well- reducing the incidence of miss-mothering

A recent study was undertaken by the Victorian DEPI to investigate the relationship between ewe mob size at lambing and marking percentage. From the 750 individual mob-paddock observations, the relationship between ewe mob size and marking percentage across all paddocks and breeds is linear. For every 100 extra ewes in the lambing paddock, marking rates drop by 9%.

The primary effect appear to be, the more ewes in a mob at lambing, means the more fresh lambs born in a day and therefore the greater the opportunity for confusion and miss-mothering in the lambing paddock. A common misconception is that if you have larger paddocks you can put in a larger mob of lambing ewes without adversely affecting lamb survival. However most often during lambing ewes don’t utilise the entire paddock, preferring to congregate for lambing in certain sections of the paddock. Hence it is the size of the nursery inside the paddock, not the size of the paddock itself, which governs the degree of miss-mothering.

Bred Well and Adapt Well

Achieving the match between production system and sheep genotype is complex. Breeding for extreme production results in a reduction in the ability of the animals to maintain reproductive function (Rauw et al. 1998) unless more resources are made available. However extreme genotypes are by definition exceptionally productive and can be a key component of an efficient lamb production system.

The most efficient use of these genetics is through providing nutrition that enables these genetics to perform to their potential. This is only economically achievable by developing pasture production systems that provide this high level of nutrition and the required pasture production systems are only suitable to the higher rainfall zones. In less favourable environments (which includes much of Australia) sheep genotypes that display robustness are likely to best match the production system.

These robust genotypes will be better able to maintain reproductive function through periods of sub-maintenance nutritional conditions which are expected in these environments. The aim should be to breed a balanced high performing sheep that suits the production environment present.

Ferguson (2012) highlighted the importance of genetic fat and muscle for improving the robustness of the breeding ewe, buffering conception rates and lamb survival in periods of sub-maintenance nutrition. Many discerning breeders, both seed-stock and commercial, have included these traits as part of their breeding objective and have started to witness the benefits. Particularly, those breeders residing in either marginal environments or with farming systems that result in the breeding ewe having regular sub-maintenance nutrition levels during the reproduction cycle.

The need to have adaptable sheep and flexible systems is an imperative when you consider the variability of the Australian climate. Recent pasture modelling undertaken as part of the More Lambs More Often workshop designed to bullet proof sheep businesses against varying seasons, highlighted that carrying capacity in a medium rainfall environment (500mm annual rainfall) varied from 3 to 15 DSE/ha from a bad year to a good year. This sort of volatility in pasture production, carrying capacity and ultimately profit means sheep businesses must have a range of strategies in place that allow flexibility, particularly in bad seasons.

Next Steps

The future challenge for the industry is to understand why some segments of sheep producers are yet to adopt industry best practice or be engaged in extension programs. With a view to establishing a wide reaching extension strategy that offers are range of pathways for producers and enhances producer involvement in initiatives such as BWFW and LTEM, so that the majority rather than the minority of the national ewe flock and its managers can be influenced by these programs.

Participation in these programs has already proven to increase the reproduction rates of the national flock and thus improve the competiveness, sustainability and ethics of production of the Australian sheep flock. A further challenge for the industry is to effectively engage with the broader public on the ethics of production, and drive product demand so that both our meat and w ool industries can ‘survive and thrive’ into the future.

.