Proposed mulesing guidelines ignore breeding alternative and markets which support it

By Patrick Francis

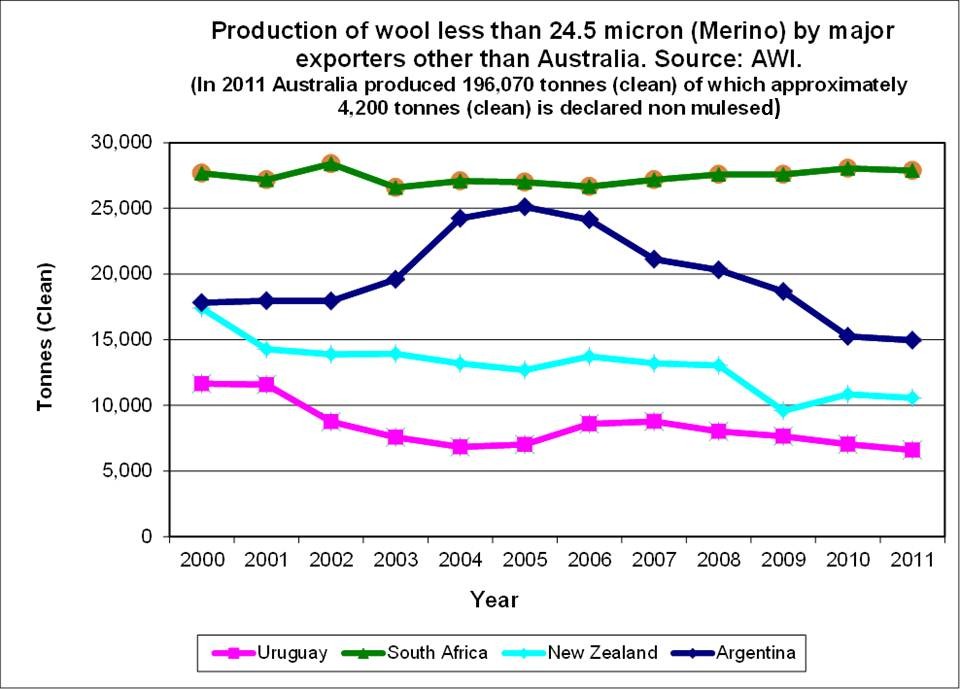

The Australian wool textile supply chain is in a dilemma over the presence of declared non mulesed Merino bales being presented for sale. A small percentage of farmers are successfully producing high quality Merino wool from non mulesed sheep which are naturally resistant to fly strike.

According to the Australian Wool Exchange (AWEX) data over the past three selling seasons, the percentage of non mulesed declared adult Merino wool bales offered for sale has risen from 3.5% to 4.8% of total adult Merino wool bales, figure 1. In contrast the percentage of ceased mulesing Merino bales has declined, while the pecentage of pain relief declared Merino wool bales has increased significantly from 9.1% in 2010/11 selling season to 17.0% in the 2012/13 selling season to March 2013.

Those farmers consigning declared non mulesed Merino wool into the wool auction system are demonstrating that genetic selection for the right skin, wool and disease resistance characteristics as well as adoption of management practices can simultaneously reduce flystrike incidence in their flocks to the point where mulesing is not required. What’s more these Merino sheep farmers have achieved this outcome between five and10 years ago.

The dilemma is twofold. It demonstrates to the Merino wool textile supply chain that product from non mulesed animals in Australia is a reasonable expectation if the industry agreed to pursue a target such as a minimum of 50% of the Merino wool clip being declared non mulesed; and secondly undermines the basis on which new sheep welfare guidelines are being prepared by Animal Health Australia.

In January the Sheep Standards and Guidelines Writing Group prepared a discussion paper “Sheep Standards and Guidelines – Mulesing” as part of discussion around revising national sheep welfare guidelines. The Writing Group sees the ‘main issues’ with mulesing are:

* Age limits before pain relief is required

* Knowledge, experience and skills to perform the task

* Availability of pain relief drugs.

What stands out is the absence of genetic selection for wool, skin and disease resistance traits which minimises breech strike so that mulesing is not required. It’s a perspective made worse by the Writing Group’s reference to breeding Merinos that do not require mulesing to prevent breech fly strike as a strategy in which “Overall, genetic progress is slow but steady with a timeframe of many years to complete solutions….”.

Factually this statement is wrong as some Merino breeders in a range of different rainfall and pasture environments have adopted genetic selection approaches which have produced such effective changes in wool, skin and disease resistance traits that they no longer need to mules their sheep. Dr Jim Watts, The SRS Company Pty Ltd, Bowral, New South Wales, Australia, is a sheep geneticist who has spent his professional life selecting Merinos for skin and wool traits which improve wool productivity, quality, fecundity and disease resistance, including the ability to resist breech and body strike without mulesing.

All 40 Merino studs selling over 11,000 rams annually which Dr Watts works with have stopped mulesing their sheep and some of their commercial clients have followed suit. He is astounded the Welfare Standards Writing Group omits genetic selection as an alternative to mulesing in the “main issues” and the reference it makes to genetic progress in this direction as being slow.

“The transition from a sheep that is wrinkly and requires mulesing to a sheep that is plain bodied and does not need to be mulesed can be less than 5 years, and in some cases as rapid as 3 years. It is not true in my experience to say that progress towards mules free status for Merino sheep is a slow process that takes ‘many years’ to complete.

“These mules-free Merino sheep are already out there in large numbers and are naturally resistant to all forms of flystrike including the most severe and challenging body strike outbreaks during wet summers. There is no reduction in wool quality and quantity, in fact we have observed improvements, and definitely the environmental fitness, and fecundity of these animals have improved,” Dr Watts says.

Dr Watts is not the only Merino geneticists who contends that five years is an acceptable period of time for selection for wool and skin characteristics to produce Merinos which no longer need to be mulesed to reduce the incidence of flystrike. In a recent interview on ABC Rural, the Sheep Cooperative Research Centre’s Lu Hogan, head of training for wool producers, said five years was a realistic time frame for Merino breeders who incorporated appropriate traits in a selection index to achieve breech strike resistant animals while maintaining other wool quantity and quality characteristics.

The implications of omitting breeding flystrike resistant sheep as an alternative to mulesing in Australia’s sheep welfare standards will be far reaching for the Merino sector. Merino wool’s share of the world textile market is at an all-time low at 1.7%. The textile’s hope for profitability at all points along the supply chain is consumer recognition of Merino as a luxury fibre with exceptional credence characteristics that demand a premium price. Australian Wool Innovations (AWI) Group Manager Market Intelligence and Reporting Dr Paul Swan emphasised the importance of the luxury market to the future of Merino wool during his industry outlook presentation at the recent Outlook conference in Canberra.

According to Dr Swan 8% of the world’s population account for 50% of global expenditure per capita on clothing and footwear, spending above $900 per person per year in 2010/11.

“The luxury apparel market is the fastest growing segment of the apparel business,” he said.

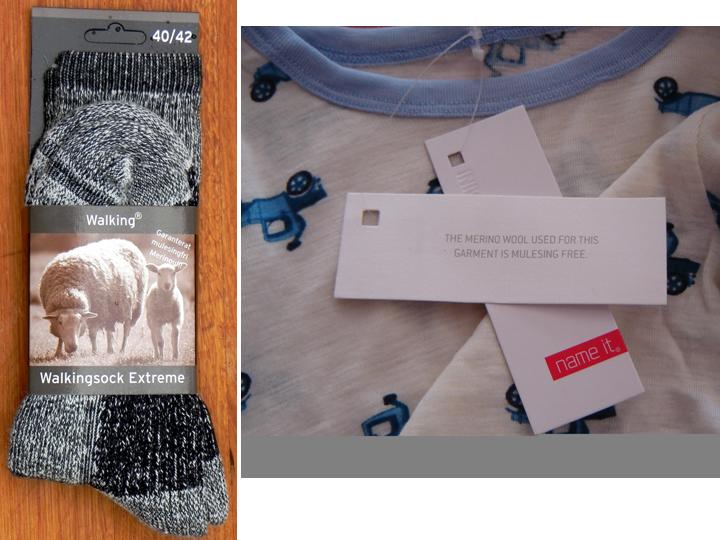

According to Dr Swan wool textile’s provenance and heritage are critical and this is based on the ability of the Merino wool sector to communicate the story of the product from farm to the existing and new emerging consumer demographics such as the ‘affluent ageing’ and ‘little emperors’. These are references to the over 50 year olds, and parents buying products for infants and children.

“Our challenge is to reinforce and communicate wools wellness and sustainability credentials to brands, retailers and consumers,” Dr Swan said.

Such an approach is soundly based but is under threat if sheep welfare is not accounted for in Merino wools credentials. The industry has been warned repeatedly for a decade that mulesing is increasingly unacceptable to consumers on animal welfare grounds but has chosen to retreat from giving high priority to a genetic selection alternative in favour of the status quo with pain relief.

The industry through its peak promotion and R& D organisation AWI no longer has any strategic plan or date for achieving a target such as 50% of adult Merino wool bales offered being sourced from non-mulesed flock.

The Writing Group’s perspective on the “main issues” confirms this industry position to the world’s textile companies and markets. In effect it is saying to Merino wool buyers and consumers that the Australian industry accepts mulesing with some pain relief options as standard practice because alternatives to it are currently non-viable. On the other hand it knows that a significant minority of Merino stud breeders have found a genetic solution which avoids the need for mulesing.

Ironically, Dr Watts says the opportunity of breeding flystrike resistant sheep is not new. He cites a 1931 trial which clearly demonstrated that plain bodied, wrinkle free sheep were resistant to fly strike. But the genetic paradigm at that time considered skin wrinkles increased fleece weight and the new technique (of the time) to overcome the issue of fly strike was simply to cut the wrinkles off the breech in the mulesing procedure.

Australian Merino wool’s dominant position in the luxury fibre market is not guaranteed. No other country has the issue of mulesing hanging over its clip, so buyers have alternative strategies to choose from – buying from New Zealand, South America and South Africa, replacing Merino with other luxury natural fibres, and purchasing from the limited supply of declared non mulesed and ceased mulesed clips. There is a definite market risk associated with not promoting the breeding alternative to mulesing and failing to seriously encourage its adoption. Buyers and retailers don’t want and can’t afford to be involved in the politics of mulesing and for some it is likely to put purchasing Australian Merino in the “too hard” basket.

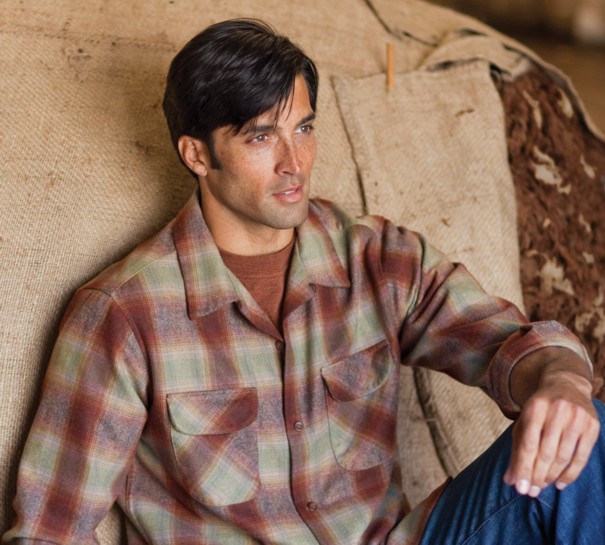

Even buying from accredited non mulesed clips has its draw backs if the volumes and types available are limited. Current figures show there are only about 30,000 non mulesed declared Merino fleece wool bales out of a total of about 800,000 Merino fleece wool bales offered in Australia each year. There must be a temptation to use another natural fibre or purchase Merino wool from another country where mulesing is not practiced. The latest (2011) world data for Merino wool production shows New Zealand, Argentina, Uruguay and South Africa produce a combined 60,000 tonnes (clean) of non mulesed Merino wool (less than 24.5 micron) per year, while Australia’s production of declared non mulesed Merino wool amounts to approximately 4,200 tonnes, figure 2. Even the Writing Group noted in its discussion paper, “The procedure is not known to be done in other countries that publish animal welfare policies and regulations”.

Pendleton Woolen Mills Portland Oregon USA demonstrates an attitude which can hurt the Australian Merino sector if breeding to avoid mulesing is not encouraged. This sixth generation family owned business specializes in fine woolen men’s and women’s clothing. Pendleton is not currently making efforts to buy or market wool from unmulesed sheep, and has no immediate plans to differentiate.

“We’re hoping the problem is solved by continued breeding efforts, and the industry can move away from mulesing before it becomes a bigger issue in the marketplace,” John Bishop, vice president of mill sales said.

A more worrying sentiment is expressed by the Nau clothing company in the US which uses Merino wool in around 20% of its clothing range. Director of Fabric and Product Development Jamie Bainbridge said wool, because it involves animals, is the most complex fabric the company deals with.

“The challenges lie in the fact that we are not wool farmers nor do we purport to know what’s best for sheep, but we as a company want to do best by the land, and the animal and the environment in terms of processing. This means attempting to address everything from traceability, biodiversity, veterinary and end-of-life practices to quality of life including mulesing and use of pesticides…Zque third-party-certified Merino wool from New Zealand, which Nau uses for all of its knits, satisfies all those factors,” she said.

These manufacturers comments are reflected across the US and Europe through the US National Retail Federation’s September 2012 position paper on mulesing which has 18 organisation signatories. It says in amongst other points:

- We agree that the genetics/breeding programs hold promise as the best alternative to surgical mulesing, particularly with respect to the highest risk factor – breech wrinkle.

- We also support the efforts by a growing number of merino stud breeders in Australia to produce plainer-bodied rams, with progeny that will be more resistant to fly-strike, yet have good fleece weight and lower wool micron size that growers need.

- In order to ensure their success, it is vital that the Australian wool industry actively support genetics and breeding research programs, and the Australian federal and state governments through Australian Wool Innovation (AWI) provide adequate funding and other support.

Despite the strong Merino wool processor and retailer push for the genetics/breeding alternative AWEX data shows momentum for it is slowing while pain relief adoption has increased, figure 1. It suggests many farmers are concerned enough about the welfare side of mulesing that they are prepared to use a relatively simple method to alleviate some pain associated with mulesing, but are not convinced that genetic selection can be used to avoid it. Furthermore this trend suggests most farmers are not concerned that world Merino wool textile market share will be in any way affected by continuing mulesing.

There is another commercial perspective associated with continuing mulesing that is yet to be addressed and that is its impact on sheep sale price. Dr Watts says some of his clients are feeling financial pressure when surplus non mulesed sheep are put up for sale. Despite having skin and wool characteristics that mean these sheep don’t require mulesing, they sell for up to $30 per head less than similar mulesed sheep. The culture within the industry to maintain mulesing as the principal method to minimise breech strike remains strong.

“The only reason I can see for the claim that the transition towards a sheep that does not require mulesing is ‘slow’ is that the adoption of appropriate selection procedures has been inexcusably slow,” Dr Watts says.

Find out more:

Dr Jim Watts The SRS Company Pty. Ltd, Bowral. NSW, Australia, Tel: IDD +61 (0) 2 48622050 Mob: 0409 364 864 Fax: IDD +61 (0) 2 48622290, E: srs@hinet.net.au , W: www.srsmerino.com . Copyright: Patrick Francis