Livestock farming review may help put brakes on “maverick” grazing businesses

By Patrick Francis

Pasture farmers who try to disguise intensive farming methods as extensive are more likely to be thwarted by changes to Victoria’s planning scheme application regulations. That will be a possible outcome if the state government adopts the recommendations of the Animal Industries Advisory Committee which it established in October 2015 to provide solutions for an out of date livestock farming planning scheme. In its response to the committee’s final report the state government has agreed to endorsing 36 of its 37 recommendations.

The issue the committee set out to address is often referred to as the “right to farm”. In short some farmers were using deficiencies in the existing state planning regulations to disguise intensive animal husbandry businesses by running them in pasture paddocks. At the same time genuine extensive livestock farming businesses like pasture based free range pig and poultry farmers are required to apply for intensive animal farming permits.

The planning permit mess was exacerbated by local government planners having little or no knowledge of livestock farming methods and pasture ecosystem functions and the lack of definitions for intensive livestock farming outside of beef cattle feedlots and piggeries.

In its executive summary the committee was accurate in stating:

“that the planning controls over intensive animal industries have let down rural communities. They have let down producers and investors – those operators who wish to innovate or expand – and they have let down their neighbours. Well‐run intensive animal operations can fit comfortably in many rural areas, but poorly‐run, or poorly‐sited operations have caused significant environmental or amenity impacts.

The current Farming Zone and other rural zone provisions do not adequately manage competing land uses in Victoria’s rural communities – in some instances farming operations are prioritised, and on other occasions dwellings.

Out‐of‐date planning controls are hindering investment and innovation and do not always deliver appropriate outcomes for those affected. Whether a planning permit is required is often difficult to determine, especially where farms are transitioning from extensive to intensive operations. This has created uncertainty for industry, planners and the wider community.

The Codes of Practice that are incorporated into the planning system are largely out of date and there are animal industries where there are no incorporated Codes of Practice.

The Committee notes that the regulation of animal industries is complex, uncertain and does not adequately respond to, or support, changing animal industry practices or community expectations.”

The committee noted that intensive animal farming activities can be broadly categorized as:

- animal welfare and biosecurity

- environmental

- residential amenity

- rural economic development

- infrastructure,

and these issues it says are not just a concern amongst “tree changers”.

“It became clear to the committee …that many of the concerns about intensive animal farming actually came from other farmers”.

The most important outcome of the committee’s deliberations was to provide guidance around specific definitions for all intensive animal production systems. It’s recommendations went a long way to achieving this objective but they didn’t go far enough.

The stand out omissions in the recommendations for pasture based livestock production were:

- Recognising and understanding the difference between paddock livestock stocking rate and paddock livestock carrying capacity. This failure is clearly seen in its recommendation to “Provide online guidance on what intensive animal husbandry definition means in terms of stocking rate for different conditions…”. The issue here is does paddock stocking rate match paddock carrying capacity throughout the year or is it exceeding it to the detriment of soil, water, pasture, biodiversity and livestock health. The committee doesn’t seem to understand the relationship between paddock carrying capacity and stocking rate.

- Recognising that pasture ecosystem functions must be protected at all times irrespective of climatic conditions. The committee’s understanding of improving paddock ecosystems functions seems limited as it is not prepared to endorse particular indicators such as minimum kilograms of pasture dry matter per hectare (eg 1200 kg dry matter per hectare which is best practice); minimum percentage soil surface plant and herbage cover (eg 70% which is best practice); and annual nutrient budgets for paddock nutrient inputs and exports per hectare.

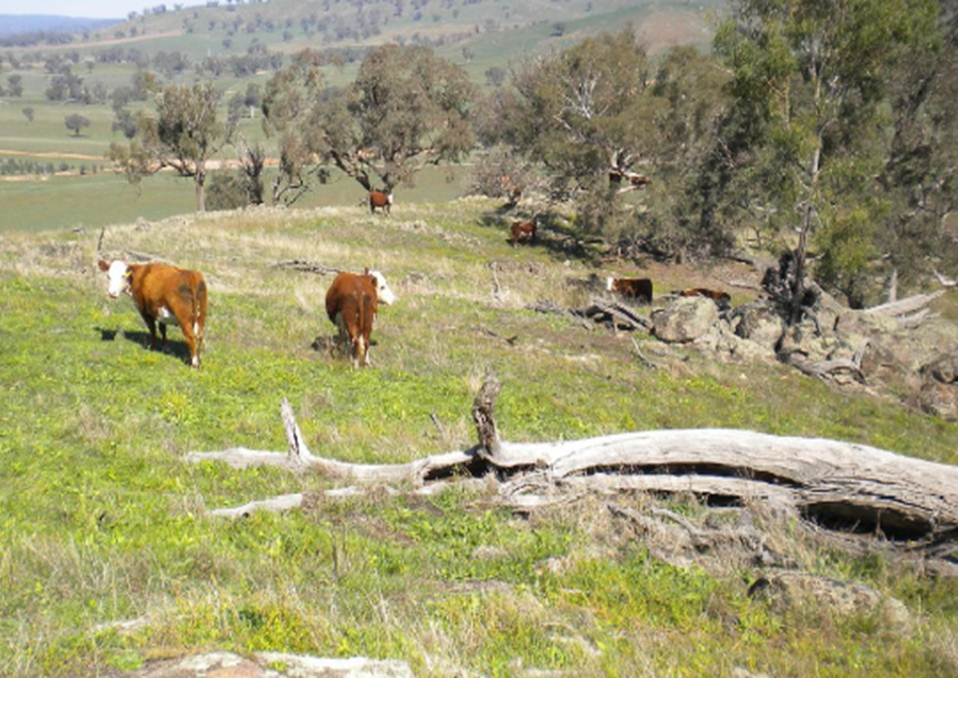

Figure 1: Protecting paddock ecosystem with plants and plant residue is critical for climate resilience, water quality, biodiversity and soil carbon.

- Failure to recognise that best practice grazing guidelines and/or codes of practice already exist for all livestock farming on pastures except for free range poultry.

- Failure to recognise in the recommended intensive animal husbandry definition that free range pigs and poultry raised in accordance with pasture management best practice or codes of practice should not be called “intensive animal husbandry” just because more than 50% of the animals’ daily energy requirement is supplied from outside the enclosure. The fact that these livestock require more than 50% of their daily energy needs provided from outside the paddock (or farm) is not relevant if pasture carrying capacity and ecosystem functions are maintained and paddock nutrient budgets are met on an annual basis.

Figure 2: Pasture raised poultry which are managed with best practice grazing management and paddocks nutrient budgets should not be classified as intensive farming.

- Failure to include points one and two above in the recommended definition for extensive animal husbandry. The outcome of this failure will be maverick and uninformed livestock producers who operate at the margin of 50% of daily energy needs coming from pasture and 50% coming from supplements causing land and water degradation during “environmentally challenged” months during the year eg in summer/autumn dry and abnormally wet winter/spring.

- Failure to recognise that there is more interest in shifting from intensive livestock farming methods into extensive methods because an increasing number of meat and animal product consumers prefer to purchase products from livestock reared on farms where ecosystem functions and animal welfare are given the same consideration as eating quality and productivity.

Figure 3: Any pasture grazing system is either best practice extensive (left) or planning permit approved intensive (right), there is no room for an inbetween method (centre). Photos: Patrick Francis

- Failure to require farmers who intensify livestock production on pasture to undertake annual nutrient budgets and manage paddock nutrient levels accordingly.

- Recommending the development of “a Code of Practice for the supplementary feeding of cattle, sheep and goats that falls short of being a feedlot”. If a pasture based livestock business is not a feedlot then supplementary feeding best practice is already well documented in industry grazing management programs. One of the reasons the National (beef cattle) Feedlot Accreditation Scheme was introduced by the Australian Lot Feeders Association in the mid 1980’s was to separate professional feeders who did the right things around pen management, waste management, environment protection and animal welfare from the “maverick” opportunity feeders who often fed animals under appalling conditions in paddocks and small yards.

- Failure to include intensively yarded horses as an intensive livestock enterprise requiring the same planning permit considerations as other intensive livestock systems. Such intensively yarded horses present the same environmental threats to water courses and soil as well as pest, weed and smell threats as any other intensive livestock enterprise.

Taken together these omissions mean the committee has failed to distinguish the difference between intensive and extensive livestock farming methods. It contends that if a livestock business is mid-scale or small-scale then it impacts on the environment and animal welfare will be insignificant and so no planning permit to operate is needed nor is there a requirement to operate under standard codes of practice. It refers to taking a “graduated approach to planning controls based on risk”. That is simply wrong as a small poorly managed livestock enterprise can be a significant source of surface and ground water pollution, soil and environmental degradation, pest animals and plants, and smell.

Livestock business is either intensive or extensive

A livestock business is either intensive or extensive irrespective of size. Even hobby or lifestyle farms need to be covered by these definitions and have the appropriate planning permits once the owners venture outside of best practice grazing management and ecosystem functions protection.

The inability of the committee to clearly define the differences between intensive and extensive animal husbandry is a constant source of confusion in the report. It is likely that in many cases the confusion arises because the committee has confused itself over what is increased production per hectare on pasture versus average production. The committee and the Victorian government has the misapprehension that livestock farmers who lift paddock carrying capacity by growing more pasture per hectare and grazing it appropriately are becoming intensive livestock farmers. The report says:

“…more intensive grazing and production systems are being adopted in the sheep, beef and dairy industries. The trend towards more intensive production systems is likely to continue, some say it needs to continue, if Victorian agriculture is to meet growing overseas demand for its produce.”

There is a significant difference between increasing livestock productivity per ha or per 100mm on pasture and intensive livestock farming.

Intensive ruminant livestock farming is not about using pasture as the principle feed source but simply holding animals in a paddock and feeding them introduced grains, hays, silages etc for their maintenance and growth.

The committee doesn’t seem to realise that under best practice grazing management conditions using rotations, stocking rates can be exceedingly high (greater than 100 dry sheep equivalents per hectare) for short periods of time without exceeding paddock carrying capacity.

Dairy farming a good example

Contemporary dairy farmers are the classic example of high pasture productivity livestock production with annual pasture stocking rate not exceeding paddock carrying capacity. The livestock on pasture are not intensively raised despite involving stocking rates of 200 – 300 dry sheep equivalents per hectare for short periods of time. On dairy farms that level of stocking rate may only be for four to six hours and the pasture mass is reduced from 2500 kg dry matter per hectare down to 1200kg dry matter per hectare. This pasture component of the dairy business managed on best practice principles is extensive livestock production.

On the other hand many dairy farms now have an intensive livestock rearing component to their businesses. That takes place on feed pads where cows are fed high energy and protein feeds in troughs. The manure and effluent from these feed pads should be collected and managed appropriately so as not to cause environmental damage. The feed pad is an area of intensive livestock production and should be covered by an intensive animal production planning permit.

Interestingly the committee did not develop a recommendation for how dairy farms with feed pads (or without them but fed intensively in a small paddock) should be treated in the planning scheme.

With beef cattle or sheep a farmer can use best practice grazing, fertilising and species selection to significantly increase pasture carrying capacity over district averages without becoming an intensive livestock producer. But once the farmer begins to introduce livestock feed into a paddock on a continuing basis such that the pasture stocking rate continually exceeds pasture carrying capacity then the enterprise has shifted from extensive to intensive.

The fact that the livestock are in a paddock not a pen is irrelevant. The consequences of stocking rate exceeding carrying capacity on a continuing basis are paddock soil environmental degradation from compaction and pugging; above and below surface water degradation from manure and nutrients; biodiversity loss across plants and animals; plant and animal pest proliferation; local amenity (noise, smell, dust) issues; and possible livestock welfare issues.

The committee’s recommendations

The committee made 37 recommendations to the state government. Outlined below are the ones I consider useful for assisting the planning process and most relevant to the local government planners and livestock farmers.

Establish a high level working group with a mix of government, industry and community representatives to facilitate continued improvement in the sector, finalise changes to planning schemes, set a framework for developing Codes of Practice and develop model planning permit conditions.

Support a program of Council based farm liaison officers to assist animal industries.

Require a permit for new Dwellings in the Farming Zone:

- For land that currently meets minimum requirements for a Dwelling, make the sole decision criteria the need to provide separation distances from intensive animal husbandry operations

- Provide flexibility on the location of the Dwelling so it can be located on other land within a larger farm holding by way of a ‘transferable development right’.

Make more information available online to assist farmers, members of the public and responsible authorities and referral authorities.

Include Declared Potable Water Catchment areas and the catchments listed in Appendix 2 of the Victorian Code for Cattle Feedlots on property reports through the Victorian government Land Channel (land.vic.gov.au).

Develop an online planning portal to provide a whole‐of‐Victorian‐government ‘one‐stop‐shop’ for access to information on animal husbandry‐related planning provisions, that includes:

- relevant Codes of Practice, standards and requirements

- a tool for ‘pre‐application’ self‐assessment against codes and standards

- links to other relevant Victorian government agencies

- links to relevant industry quality assurance schemes that adopt Victorian codes or standards.

Develop and make available a short course through the PLANET program on strategic rural planning matters, applying the animal industries codes and case studies as a collaboration between the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources; the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning; the Environment Protection Authority and the Victorian Farmers Federation.

Release Environment Protection Authority complaint data to Councils to allow Councils to incorporate any relevant complaint data into monitoring or enforcement proceedings.

The Victorian government responded favourably to 36 or the 37 committee recommendations. They were either “supported’, “supported in principle”, or “further investigation required”. One was not supported.

Take home messages

Given the committee failed to understand what constitutes best practice grazing management which protects ecosystem functions, and the state government support virtually all its recommendations it is unlikely that the changes to be made to planning procedures for livestock enterprises will make a significant difference.

But one ray of hope is contained in the committee’s Recommendation 1 which the government has supported. It reads: “Government will establish and implementation reference group to facilitate continued improvement in planning for sustainable animal industries”.

If the group contains some individuals who understand the links between best practice livestock production on pasture and paddock ecosystem functions, there is hope that maverick farmers and uninformed landowners will not be given permits to operate.

Finally it is relevant to look back at the views of CSIRO Wildlife and Ecology scientist Robert Lambeck in the book “Farming Action Catchment Reaction – the effect of dryland farming on the natural environment”, published in 1998. He wrote:

“The management of productive lands in Australia, …has generally been undertaken with little regard for the sustainability of the productive enterprise or understanding of the ecological implications of the land uses that have been adopted. Consequently many of our primary industries have generated wealth at the expense of the health of the land systems upon which they are based.

“The problems have arisen primarily as a result of managing the various components of the farm system in relative isolation, with a focus on our productive requirements. We have failed to recognise the interrelated functioning of the different components of the landscape as a result of their bring linked through processes of material and energy transfer…. This failure has resulted in actions at one place having and unwanted or deleterious effect in others.

“Understanding the factors that generate and control the fluxes of energy, water, nutrients and biota between different landscape segments is critical to proper planning and management”.

If revision of the planning system is going to support animal industries in Victoria, the planners need to understand what Lambeck is saying.