PCAS starts grass finished beef marketing games

By Patrick Francis

The discussion and one-upmanship surrounding the domestic marketing of beef produced from cattle grazing pasture for their entire lives is reaching absurd levels. Australian beef farmers most common form of beef cattle raising is being manipulated as if it’s some sort of extraordinary production system which foodie consumers are only just coming aware of. In truth, most beef from cattle raised on pastures has remained unidentified for years in supermarkets and butcher shops due to the post farm gate’s sector of the industry reluctance to identify its origin. For the last 15 years the industry’s ability to identify origin has been ignored.

A recent ABC Rural report on the subject contained claims by farmers and butchers that grass finished beef costs more to produce so its price for consumers must be higher; and that grass finished cattle have lower carcase yield than grain finished animals with no reference to comparing animals at similar age, weight, muscle score and fat score. It was also stated that grass finished beef is a healthier meat than grain finished, again without any reference to comparing similar weight and fat score animals and the number of days on feed in the feedlot.

The reality is most of these comparisons are misleading without reference to details which enable valid comparisons to be made between feeding systems.

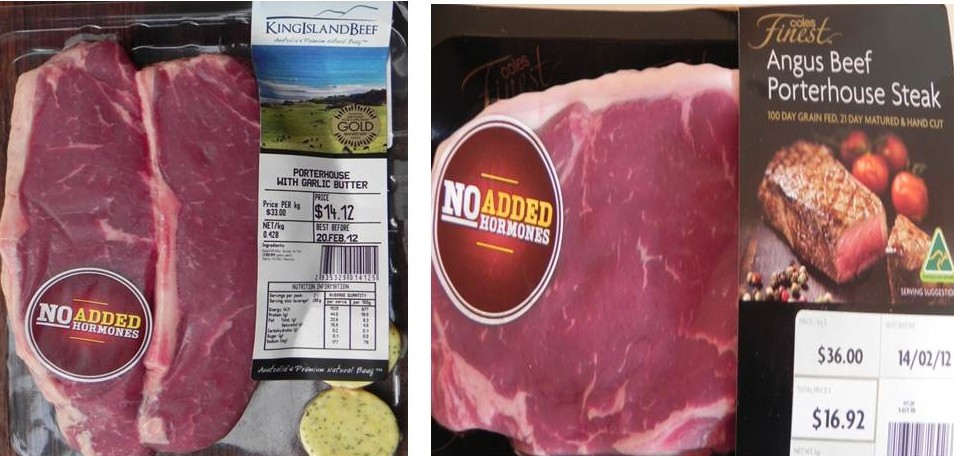

The whole debate about grass versus grain finished beef is being further complicated by failure of Meat & Livestock Australia and Cattle Council to clarify for consumers the logistics of beef production in Australia. Despite the fact that beef cattle prices are deplorably low with the Eastern Yearling Cattle Indicator at a level it was 10 years ago, these two organisations have been unwilling to encourage beef retailers to identify the production systems behind the house brand meats in their meat display cases. Apart from some well established pasture reared cattle beef brands such as King Island Beef, Angus Pure, Greenham Tasmanian Natural Beef, most beef is unidentified as to whether it was finished in a feedlot or spent its entire life on pasture, figure 1.

![]()

Figure 1: The majority of beef in supermarket and butcher shop display cases provides consumers with no indication about the production system involved yet it is all covered by Livestock Production Assurance which should identify if grains are fed.

If the demand by consumers for grass finished beef is so strong that they are willing to pay a premium for it and in turn producers receive a higher prices for their cattle, why is that the Livestock Production Assurance declaration does not contain the question “Have the animals in this consignment been feed a grain supplement or grain finishing diet in their lifetime?” Given farmers can provide life time traceability with LPA and the National Livestock Identification Scheme (NLIS) then such a question is vitally important for marketing and the opportunity to improving business profitability.

It is ironic in the extreme that LPA can be used to differentiate between animals fed or not fed hormone growth promotants and antibiotics, two important criteria for consumers selection of a beef meal, yet the same scheme is not being used for a 100% grass finished declaration. LPA’s Section 3C Livestock feeding record ensures farmers giving feedstuffs to cattle record the feedstuff description, identifies the mobs fed, and the duration of the feeing period.

Instead of using this opportunity with LPA, Cattle Council has adopted the Pasturefed Cattle Assurance System (PCAS), a third party audited certification program, to assure consumers that the beef involved has “never ever been fed grain”.

Cattle Council contends PCAS certification is important to give consumers the confidence to buy pasture finished beef without any reservation. Yet PCAS farmers must pay (a management fee to Cattle Council and annual audit fee) for the privilege of certifying their pasture management system despite the fact most are unlikely to have never used grain feeding. The reality is most Australian beef cattle farmers can finish cattle on pasture and many do so because it’s the most cost effective way of livestock farming.

When seasonal conditions are such that pasture finishing is not possible then many cattle are consigned into feedlots, most now into professional lots rather than been fed grain on-farm. As well, some cattle production systems, especially in low rainfall, rangeland districts are not suited to finishing on pasture so young cattle are consigned to feedlots. Thirdly there is a “satisfying beef meal” component to grain finishing which helps to ensure meat quality and tenderness meets a minimum consumer standard. Grain finishing has important role underpinning the beef cattle eating quality assurance and maintaining market outlets for young cattle particularly in years with poor seasonal conditions. Even certified organic beef production systems allow the use of grain feeding during seasons when finishing cattle on pasture is impossible. The “never ever grain feeding” requirement of PCAS is fine in theory but a negative for beef marketing from cattle reared under drought conditions.

Figure 2: Grainfed beef has an important role in providing consumers with a satisfying beef meal, especially from cattle bred in districts where pasture quality is insufficient to finish animals. Its cost of production will always be higher than equivalent weight cattle finished on pasture.

Satisfying beef meal

Most of the commentators who talk so highly of pasture finished beef, have forgotten the discussions during the 1980’s and 90’s associated with declining beef consumption in the wake of highly variable eating quality. Grain finishing and in the last 10 years Meat Standards Australia grading for grass finished cattle underpin eating quality and subsequently consumer satisfaction with beef. Despite this effort consumption per head of population continues to decline in Australia while other more price attractive meats are increasing market share.

Price is important to consumers and despite what some farm consultants contend is also important for producers. An Eastern Yearling Cattle Indicator price today similar to what it was in 2004 is unsustainable for commercial businesses even if they are in the Top 25% for productivity per 100 mm of rainfall.

Figure 3: Grass finished brands of beef demand a premium based on consumer trust about ethical values (eg HGP free, geography) combined with quality assurance (eg MSA grading) compared with unidentified beef with QA.

Some consumers will pay more for beef brands they trust, it’s why King Island HGP free, grass reared cattle porterhouse commands $34/kg; why Greenham Tasmania Natural Beef porterhouse commands $29.99/kg, and why Woolworths PCAS Sustainably Produced Grass fed porterhouse commands $32.99/kg, figure 3. But most consumers prefer to pay $20.99/kg for Woolworths MSA porterhouse without knowing if it is grass finished or grain finished.

Farmers who only use pasture to grow cattle should be able to access some of the $10/kg (Greenham) to $14/kg (King Island) premium by meeting similar embedded consumer requirements such as grass finished, HGP free without resorting to expensive third party auditing to certify the fact they do what they say. All the beef cattle industry needs to do is to add the grain feeing question on the LPA declaration then lobby supermarkets and butcher shops to follow through and indicate pasture or grain finished status on beef cuts. MLA spends millions of dollars annually on marketing beef domestically, yet it has so far failed to embrace this simple strategy with consumer appeal.

What Cattle Council has lost sight of with PCAS is that livestock farming QA is about trust not red tape. If Greenham and JBS Swift (King Island) and others like Certified Australian Angus Beef’s “Angus Pure” brand can engender trust in their pasture finished brands without third party auditing, then other companies can do the same without adding extra costs onto beef cattle producers whose profitability is declining.

David Warriner, president of the Northern Territory Cattleman’s Association recently said $3 per kg live weight was the price needed for producers to cover their operating costs, to provide adequate funding for marketing and productivity research and to maintain and improve the industry’s social license to operate. Interestingly the $3 per kg liveweight figure is closer to what certified organic producers receive for their beef. It subsequently enables them to pay for the auditing associated with organic certification and specific costs like transport to certified abattoirs and feeding certified organic feedstuffs when and if required. Even amongst organic beef producers, especially those in southern Australia with relatively small herds, organic certification which encompases paying for an annual audit is becoming uneconomic for some farmers. While maintaining organic farming principles those farmers opting out of certification are relying on consumers trusting what they say to do and subsequently paying a premium price for their beef.

The question of auditing for certification needs far more investigation than is provided with PCAS for grass finished beef. PCAS beef doesn’t sit in a sufficient premium price market segment that can command a price to farmers that justifies auditing. Similar certified organic beef cuts are available at the same price, figure 4. Certified organic beef for credence orientated consumers carries far more appeal that PCAS, yet auditing costs are likely to be about the same, while the price received per kg carcase weight for organic beef is significantly higher.

Figure 4: Certified organic beef carries a “grass fed” claim but is accompanied by a range of other credence values which are used to attract consumers to pay a premium. It is interesting that PCAS porterhouse steak attracts a similar price to its certified organic equivalent but carries far fewer credence values.

PCAS branding is a useful alternative marketing avenue for pasture based cattle farmers to be involved with, but it needs to drop the Cattle Council registration fee and the third party audit. It can gain its “lifetime on pasture” credibility via a question added to the existing National Vendor Declaration certificate which is a legally binding document.

Pasture based beef cattle farmers need to be honest with consumers about their cost of production. It is the most cost effective and environmentally efficient means of beef production when managed appropriately for holistic outcomes. Australian consumers should not be hood winked into thinking buying pasture finished beef is something special, rather it is buying a high eating quality product (when accompanied by MSA grading) , a high environmentally positive products (when accompanied by Environment Management System outcomes evidence) and an animal welfare friendly product (when accompanied by welfare organisation documentation). Depending on the number of attributes associated with the grass fed cattle, the consumer can recognise why the cut is priced and why it is worth paying a premium above unidentified beef.

To claim pasture finishing beef cattle is more expensive per kilogram of liveweight gain than grain finishing is simply wrong or is mischief making to gain a price premium. The industry should be lobbying harder for a fair price for livestock based on transparent real rather than perceived costs of production.

Figure 5: Beef farmers and retailers need to be honest with consumers about costs and only demand a premium above lower price meats based on real costs of production and added or alternative credence and eating quality values.