Bulky pastures best defence against new born lamb exposure deaths

By Patrick Francis

A feature of grazing management on Moffitts Farm is allowing summer active perennial grass species in lambing paddocks to flower in spring. As a consequence of this happening over a number of years, the plants have developed large “bushy” crowns up to 20cm across and grow numerous tillers with leaves up to 30cm high after 8 to 12 weeks rest from grazing.

In conventional short rotation and high pasture utilisation grazing management such a practice is frowned upon and considered to be “wasteful” of pasture as it is not being eaten. In contrast we see plenty of ecosystem services being generated by our high herbage mass pastures, there is also a significant lamb survival and plant resilience advantages associated with them.

This approach to grazing management in lambing paddocks in association with planting conservation corridors and forestry blocks around the farm results in two tiers of lamb protection on cold, windy and possibly wet days during winter/spring lambing:

- Macro level protection from shelter in conservation corridors around all paddocks, and

- Micro level protection within the paddocks irrespective of wind direction from the tall, thick high herbage mass perennial grasses.

We contend both levels are needed to produce the highest livestock welfare and lamb survival outcomes in our climate as well as improving ecosystem services across the farm. However, micro level shelter, that is, from high bulky pasture gives the greater contribution to lamb survival and weaning percentage.

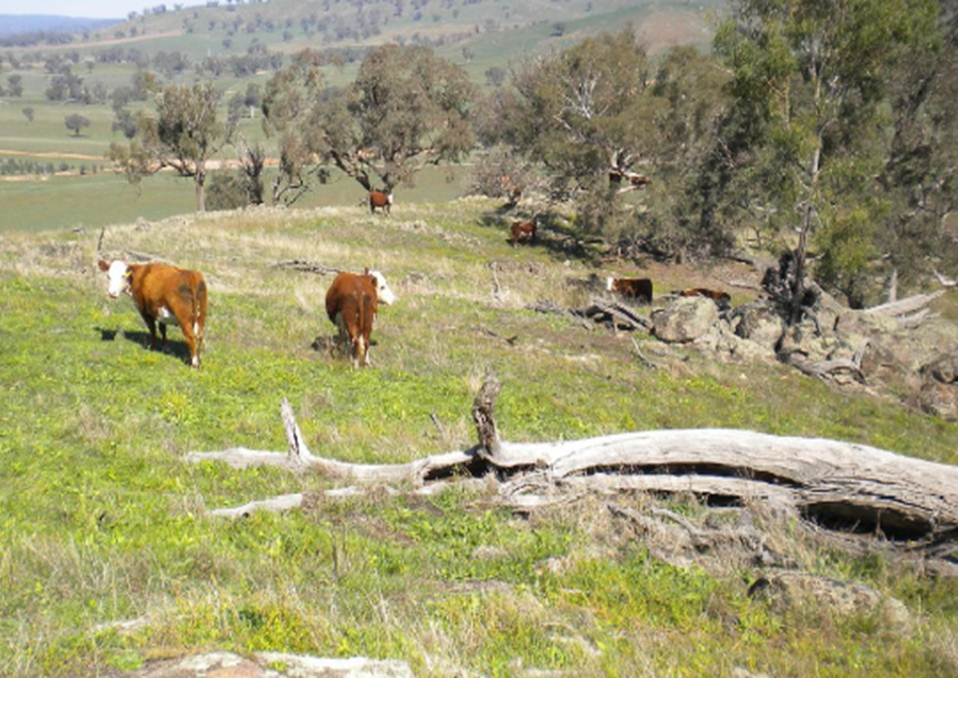

Figure 1: Moffitts Farm has 26% of its land devoted to conservation corridors and forest blocks which provide a macro level of shelter for new born lambs. While this is helpful it is the micro level shelter provided by bushy perennial grasses which gives the greatest impact on ewe nutrition and lamb survival.

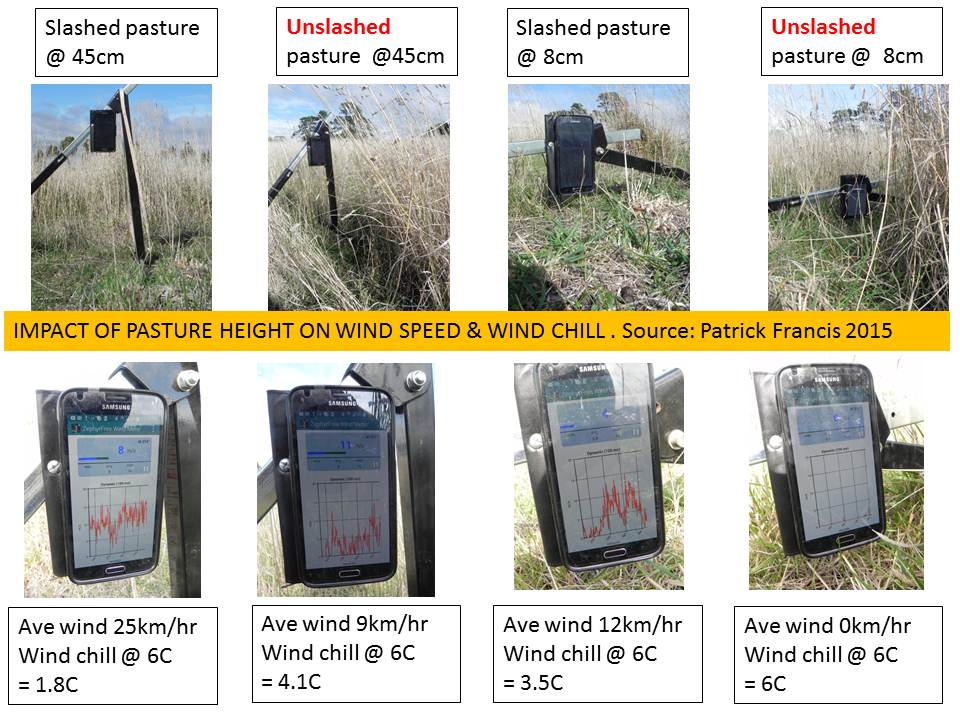

I recently found a wind speed app on my mobile phone, plus a related wind chill conversion app which are being used to test wind chill across our bulky herbage paddocks compared with a section in the paddocks where the pasture has been slashed. The results are extraordinary and highlight how simple it is to make a difference on lamb survival. While a high rate of lamb survival is economically important for a profitable sheep breeding business it also is important for a credible sheep welfare program.

Our results show that wind speed at 8cm above the soil surface can be reduced to close to zero in pastures containing 2000 to 4000 kg herbage when perennial plants have large crowns with leaves and old stems 20 -30cm high. This means no wind chill impact on extremely cold windy day, figure 2. Even at 45 cm above the soil surface these bulky pastures reduced wind speed and subsequently chill by about 50% compared to slashed pasture. An added advantage of in-pasture protection is that it happens irrespective of wind direction and applies across the entire paddock.

In contrast, in pasture that has been slashed (on other farmers grazed to achieve high utilisation rates) to leave approximately 1200 kg/ha of herbage to a height of 4 cm, wind speed was 12.5 km/hr at 8 cm giving a wind chill of 3.5C on a 6C temperature day. At 45cm above the surface the wind speed was 25km/hr giving a wind chill of 1.8C on a 6C temperature day. Daytime maximum temperatures below 10C with strong winds (above 20km/hr) are common in our district through June, July and August; they can also occur in May and September.

Figure 2: Wind chill is reduced to zero at 8cm above the surface in bulky perennial grass pastures on Moffitts Farm.

Wind chill combined with wetness (rain or mist) challenges new born lamb’s ability to maintain core body temperature and increases death rates. In our bulky pastures the “wet factor” is far less important as wind chill has been removed.

What happens to lambs exposed to cold wind was described by J C Pollard in a literature review of shelter for lambing sheep in the New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research, March 2010. What is interesting about Pollard’s review is that most of research surrounding shelter, ewe and lamb behaviour, and associated contributors to lamb mortality, was conducted 30 to 50 years ago. His description of why lambs die from exposure is important to understand:

“Being well-equipped for a rapid heat production response, the newborn lamb is able to maintain body heat fairly easily, unless it is exposed to wet or windy conditions (Alexander 1958). The effects of wind and evaporation (of rain or amniotic fluid) appear to be additive and both cause lambs to die at temperatures that they can tolerate when dry or in still air (Alexander 1958, 1985).

Deaths from hypothermia occur when heat loss exceeds heat production. Cold exposure can cause lambs to die before they manage to reach their potential heat production, or after they reach this but conditions are so cold that their heat loss exceeds their heat production, or after they successfully maintain homeothermy for some time then run out of energy reserves (Andrews & Mercer 1985). Holmes & Sykes (1984) estimated that an effective temperature of about 0°C may create safe conditions for newborn lamb survival. This would require

shelter to maintain wind speeds below 3 km/h at 5°C and below 10 km/h at 10°C(Ames 1981 in Holmes & Sykes 1984). Obst & Ellis (1977) observed that in Merino and Corriedale flocks, over 70% of newborn twin and single lambs died during wet, windy weather, whereas 5-10% died in calmer, dry weather.”

This is exactly what the 20 – 30 cm high pasture at Moffitts Farm did. It eliminated wind altogether behind the grass tufts across the paddock, irrespective of presence of shelter belts.

Shelter belts help but have problems for survival

In most reports about protecting new born lambs from exposure like “The Economic Benefits of Native Shelter Belts Report 01/14” from the Basalt to Bay Landcare Network,, shelter belts planted around and in paddocks are advocated to be the answer to reducing death rates. Pollards review is no exception. While they are important for a host of ecological functions they are in my view overstated for lamb survival compared to in-paddock herbage mass. Without doubt in conventional grazing management where pastures are maintained at 700 to 1500 kg of herbage mass, shelter belts make a difference for lamb survival. But in themselves are not enough to make a large difference.

From my observations of lambing ewes, shelter belts in low herbage pasture paddocks encourages congregation of sheep behind the belts on sheep weather alert days. But if a ewe gives birth behind a shelter belt where dozens of other ewes are congregating two things are likely to happen:

- The lamb or lambs could be confused and attracted to other animals resting nearby. The ewe giving birth has trouble keeping track of her young and in case of twins one lamb may miss-mother and die.

- The ewe giving birth needs access to plenty of pasture within 10m of the birthing area for approximately 8 hours. Pastures in vicinities of shelter belts are usually quickly overgrazed and soiled by manure, so when a ewe lambs behind the shelter she is impelled to move away from her lamb to find acceptable pasture. If her lambs don’t follow immediately they are likely to wander into other ewes and follow them into the paddock when they go to graze – it’s another opportunity for miss-mothering.

Pollards lamb mortality review confirms these points:

“Shearing ewes (this is a strategy used by some farmers in the belief it encourages ewes to seek shelter when lambing so theoretically reducing lamb exposure deaths) close to lambing time could reduce lamb survival, especially if shelter is limited. This is because firstly, shorn ewes congregate in sheltered areas, increasing the chances of mismothering. Young lambs will approach any nearby ewe (McBride et al. 1967; Bareham 1976) and parturient ewes readily bond onto any newborn lamb (Poindron & Le Neindre 1980). Secondly, ewes experiencing cold conditions sometimes desert their offspring (Obst & Ellis 1977). Thirdly, a shorn ewe is likely to provide less shelter to a lamb from her own body, compared with an unshorn ewe. Young lambs acquire a good deal of shelter by huddling into the ewe (Charles 1991). A shorn ewe would provide less bulk to protect the lamb from the wind when resting and probably spend less time lying down than a woolly ewe (Lynch & Alexander 1976).”

In contrast, in bulky pasture paddocks with or without surrounding shelter belts, these three events are less likely to occur. In bulky pasture the lambing ewe has plenty of opportunity to find a protected and relatively private birthing area anywhere across the paddock. It also provides her with plenty of high quality food around the birthing area so lambs can safely sleep in the area with the ewe only 5 to 8m away for at least the first 8 hours. In this situation miss-mothering opportunities are significantly reduced compared with ewes lambing behind shelter belts.

So high herbage content pastures with vertical structural components from leaf tillers and previous spring’s flower stalks (these characteristic are specific to species like cocksfoot, tall fescue and phalaris) play a multiple roll in preventing new born lamb deaths:

- They reduce wind chill impact to close to zero

- They provide ewes with private birthing areas, and

- They provide ewes with good nutrition within the birthing area.

The importance of a private birthing area was noted in Pollard’s review:

“The suitability of birth sites in providing isolation, shelter and grazing for the ewe may be a major factor affecting the outcome of lambing, especially in multiple litters. Undisturbed sheep can spend several days on the birth site, and in twin litters, time spent on the birth site was negatively related to the incidence of separation of a lamb from the litter (Alexander et al. 1983, 1984; Putu et al. 1988).”

Figure 3: When lambing paddocks have bulky perennial grasses in abundance lamb survival is far higher as a result of better animal nutrition, protection from the elements and birthing privacy which lowers the opportunity for miss-mothering. Note the vertical and firm structural characteristic (previous spring’s stems) which support growing tillers of the cocksfoot and tall fescue plants which are an important feature for wind protection. The other critical feature of this pasture is that protection is provided irrespective of wind direction and position of the birthing area within the paddock. Photo: Patrick Francis.

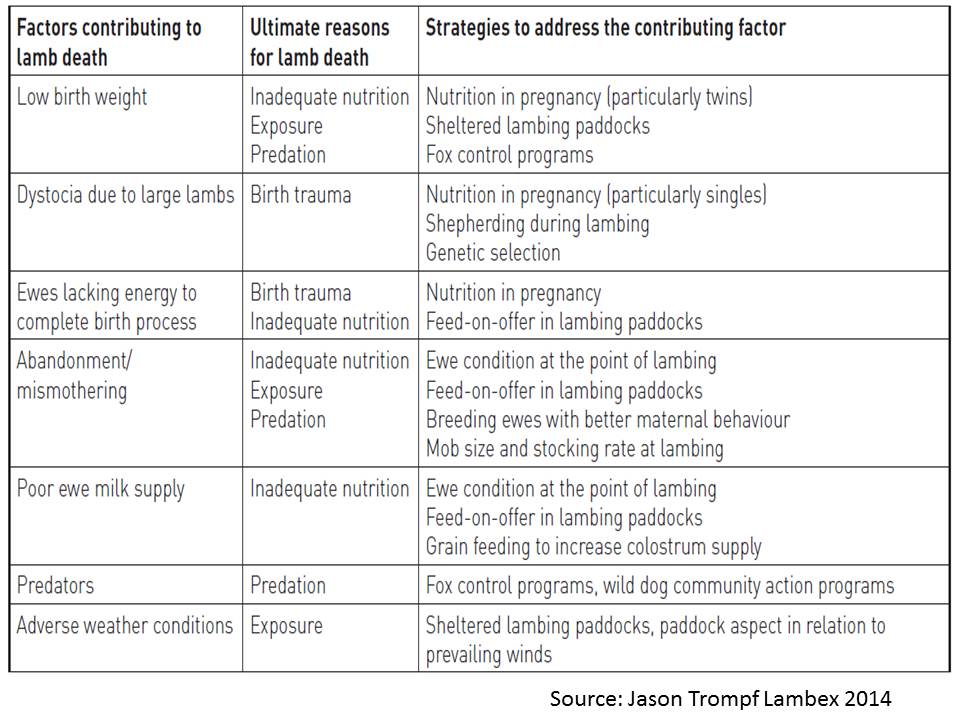

When Jason Trompf presented a paper at Lambex 2014 on increasing lamb survival he showed a table summarising the contributing factors to lamb death, table 1. For virtually every factor involved ewe nutrition and shelter are involved.

Maternal behaviour score

Another factor not considered by Pollard or Trompf in their review but is becoming increasingly apparent by some farmers is the impact of ewe temperament on lamb survival. Dr Julie Everett-Hinks, AgResearch, New Zealand has introduced the concept of ewe Maternal Behaviour Score which is a method of rating ewes based on their lamb protective behaviour in face of a threat, in particular the farmer walking or driving in their paddock (see article on www.moffittsfarm.com.au for details). The concept of breeding and selecting ewes based on their behaviour is not new in animal science as flight behaviour is also associated with ease of handling livestock and meat quality outcomes.

In terms of influencing lamb survival having ewes with high scores, that is are not particularly afraid of humans can be a valuable asset. It is also has wider animal welfare ramifications because in flocks where lambing ewes are comfortable with humans checking them, less ewes and lambs will die from dystocia related conditions as the owner/staff can shepherd flocks, that is intervene with minimal stress to the ewe concerned and other ewes in the flock. In contrast in flocks where ewes are frightened by humans (have low maternal behaviour scores), owners often prefer not to intervene during lambing as their presence causes animals to flee the birthing zone adding to lamb starvation and miss-mothering mortalities.

Table 1: Factors affecting lamb survival. Source Jason Trompf, Lambex 2014

One word of caution associated with high herbage mass pastures at lambing, they also offer some visual protection to foxes, in other words they may have an advantage stalking sleeping lambs. But that’s probably no more of a threat than stalking lambs suffering from hyperthermia. The solution in both cases is the same, fox control must be implemented before and during lambing.

Figure 4: An unrecognised feature of bulky high pasture mass pastures is that the ewe is comfortable to lie and ruminate anywhere in the paddock as the pasture provides protection from wind in any direction. She also spends less time grazing and more time ruminating as intake per bite of pasture is higher; the extra time ruminating contributes to keeping her lambs warm. Photo: Patrick Francis.

Box story

Expert fails to make vital high herbage mass connections

In a NSW Department of Primary Industries webinar on lamb survival in May 2015, sheep industry expert Gordon Refshauge highlighted the enormous losses experienced across Australian sheep farms at lambing.

He said 10% of single lambs and 30% of twin lambs die at or soon after birth. From his analysis of lamb post-mortems the causes of deaths were:

- Dystocia 48%

- Starvation from miss-mothering and exposure 25%

- Abortion and prematurity 10%

- Predation by foxes and dogs 7%

Impact of weather exposure was not determined but is generally associated with starvation as the lamb quickly losses the body fat reserves it is born with to keep warm and is unable to suckle enough milk to stay alive.

Refshauge made no mention of bulky pastures as a possible solution to preventing exposure in cold districts and providing a high plane of nutrition to ewes prior to and at lambing which helps overcome some causes of dystocia as described in table 1. Instead he commented that pasture herbage (as dry matter) mass above1100 to 1400 kg made no improvement to lamb survival percentage. In typical south eastern Australia improved pastures this is a pasture height of 3 to 5 cm. As demonstrated in slashed pasture on Moffitts Farm, low height exposes lambs to potential massive wind chill impacts when temperatures are below 10C.

How great losses can be in a severe cold weather events were referenced in Pollard’s review:

“In another Australian study, rectal temperatures of 3-hour-old lambs of Australian and British breeds were found to be lower in rainy conditions than in dry weather. A high proportion (52% across all breeds) of lambs born on rainy days died, even though most of them had managed to suck (Arnold & Morgan 1975). Similarly Obst & Ellis (1977) observed that in Merino and Corriedale flocks, over 70% of newborn twin and single lambs died during wet, windy weather, whereas 5-10% died in calmer, dry weather.”

Pollard’s review of lamb survival in cold climates highlighted the value of “tussocks” in pastures. While in botanical terms tussocks are a particular grass species, on Moffitts Farm the perennial grasses managed to allow them to form large and tall herbage mass produce the same protective effect. Pollard found:

“Tussocks have been promoted as ideal lamb shelter by several authors. Bird et al. (1984) suggested that in Australia, scattered tall native Poa tussocks should be retained in paddocks as these would provide shelter for lambs regardless of their mothers’ sheltering behaviour, and prevent ewes from deserting their lambs in bad weather. In Scotland, Cresswell & Thomson (1964) found that within tussocks, wind speed at lamb height (9 inches) was 40% of that at 4 feet, while in an open area, wind speed at lamb height was 80% of that at 4 feet. These authors considered that tussocky pastures afforded good shelter from wind and probably rain and snow, as well as providing fodder in snow conditions. Holmes & Sykes (1984) also favoured tussocks as dispersed shelter for lambing in the hill country of New Zealand, noting that scattered shelter would accommodate the tendency of ewes to lamb in isolation from other sheep.”

Figure 5: Shelter belts without bulky pastures encourage ewes and lambs to mass together, increasing the opportunity for miss-mothering amongst new born lambs. Photo: Patrick Francis

Refshauge’s suggestion for ameliorating wind impact on sheep was ensuring lambing paddocks were protected by tree shelter belts and or were less exposed to prevailing cold winds.

Refshauge also missed some important co-benefits of high herbage mass C3 pastures (measuring 10 to 20 cm high with 2500 – 4000 kg of green herbage) for lambing ewes including their:

- Contribution to ewe nutrition in and around the private, birthing area which ensures the ewe does not need to move far from her new born lambs in the critical first eight hours after birth.

- These pastures mean ewes are eating plants with balanced mineral composition so there is less change of metabolic diseases associated with low food on offer pastures such as twin lamb disease (lack of energy in diet), hypocalcaemia (lack of calcium in diet) and hypomagnesaemia (lack of magnesium in diet) , figure 6.

- The pasture height ensures ewes and latter lambs are eating above the zone where infective internal parasite larvae live, so parasite control may not be necessary.

- The pasture height ensures ground cover is always close to 100% so all rainfall soaks in and opportunity for loss of nutrient and soil is minimised.

- The baulky perennial grasses have deeper roots and more extensive root systems than short grasses so they have more potential to explore a larger soil area in association with soil food web organisms and in particular soil fungi. Their requirement for artificial nutrients is generally lower than in short root pasture species which need nutrient support.

- Baulky perennial grasses are more resilient to water logging and dry periods and persist for longer

- Baulky perennial grasses protect and enhance the soil food web and subsequently above ground biodiversity.

Figure 6: Bulky pastures have more mature leaves which contain a balance of key elements. In contrast short pastures can have elements out of balance leading to metabolic diseases.