Textile Exchange Analysis injects division among farmers, brands and consumers

Contends regenerative agriculture farmers are more socially and environmentally responsible than the rest

By Patrick Francis

Regenerative Agriculture has become an identifier or brand for an increasing number of farmers who want consumer, retailer and government recognition for the way they farm. The assumption is their farming methods improve ecosystems functions across the farm and catchment, improve animal welfare, and improve soil health and quality. In contrast the remaining farmers are by default “industrial” farmers who ignore ecosystem functions, ignore animal welfare and degrade soil health and quality. The perception given to the general public is that farmers who identify as regenerative are somehow more environmentally responsible than those who don’t.

And there is another dimension to regenerative agriculture credentials which is adding more division between farmers, that is its so called social justice or social responsibility agenda. Some regenerative agriculture groups and participants are now contending they are more socially responsible than other farmers.

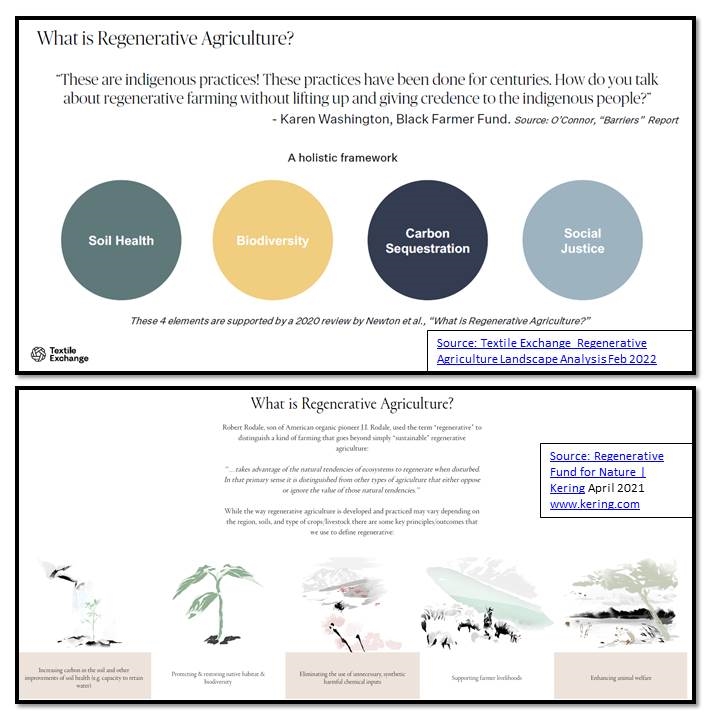

It is a distinction clearly demonstrated in the February 2022 release by the Textile Exchange of its “Regenerative Agriculture Landscape Analysis Report”. It’s objective is to provide natural textile processors, clothing manufacturers and retailers with a guide to plant and animal fibre farmers they should be purchasing raw materials from.

According to the Textile Exchange “regenerative agriculture is an opportunity for the fashion and textile industry to invest in a fundamentally different system. It drives numerous benefits for people and the planet, prioritizing justice, equity, and livelihoods.”

Figure 1: Textile Exchange interpretation of Regenerative Agriculture (top) puts a considerable emphasis on farmers “social justice” credentials amongst other features embraced by the original Rodale approach (bottom).

The Textile Exchange has developed “cradle to grave” standards for natural textiles including, wool, and cashmere. Its standards are being increasingly adopted by the world’s major textile brands and retailers. Given it is advocating for its own interpretation of regenerative agriculture as the way textile farmers should operate the question is will it require farmers to adopt it to obtain its certifications?

There are a range of issues associated with the Textile Exchange adopting its version of regenerative agriculture as the preferred farming method:

* Firstly, there are no definitions for what regenerative farming entails, unlike organic or biodynamic farming which have strict rules about methodologies and inputs. With such wide interpretations of the term advocacy for it has limited relevance for value chain participants wanting to support tangible environmental, social and economic outcomes.

* Secondly, the farming methodologies promoted as regenerative agriculture are used by most farmers and are constantly being refined to produce tangible outcomes as science and experience uncovers better methods.

* Thirdly, the Textile Exchange’s report specifically refers to regenerative farming as avoiding “extractive” farming methods, but no food or fibre can be produced without being extractive because they all contain major and trace elements. Without explanation it contends that natural textiles can be produced on regenerative agriculture farms without extracting elements from the soil.

* Fourthly, it is judgemental about individual farmers social justice credentials. It can be interpreted that farmers who are not participants in regenerative agriculture are likely to be less socially responsible.

In the same week as the Landscape Analysis Report was released, the Grains Research & Development Corporation hosted a grains research update in which CSIRO scientist Dr Mark Farrell presented a paper “Building carbon with regenerative farming – is it possible?” While the Textile Exchange contends that regenerative agriculture is far more than adopting management that builds soil carbon it is an important outcome of the methodology. The Landscape Analysis makes no mention of the fact that conventional or so called industrial farmers have the same objective but usually with greater emphasis on building soil organic matter (SOM) of which approximately 50% is soil organic carbon (SOC).

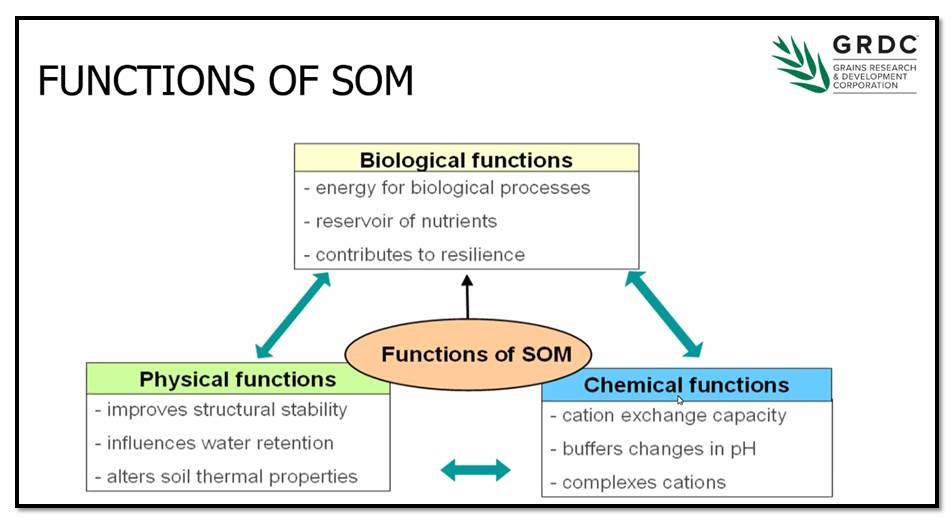

Farrell points out “Soil organic matter is responsible for provision of nutrients (particularly N), maintaining a diverse and healthy microbial community, infiltration and water retention, amongst others. It can be separated into three measurable fractions, with distinct properties for nutrient supply and stability. In addition to SOC, two smaller important pools of C exist: microbial biomass C (MBC), which typically contains approximately 1% of the total organic C in a soil and represents the C stored in live microorganisms, and dissolved organic C (DOC) which is the soluble fraction. This latter pool contains most of the C”.

So in terms of building SOM and subsequently SOC conventional farmers have been practicing methodologies, often for decades, which have virtually the same objectives as so called regenerative farmers, figure 2.

Despite this, reference to building soil organic matter is often highlighted as something new to farming. A 2021 AgriWebb survey of farmers across Australia, US, and UK is a good example . In the survey results report released in February 2022 it stated under the heading The Future of Regenerative Farming that “No doubt some landowners are skeptical of this “new” way of agriculture because it’s what they’ve always been doing. …Regenerative agriculture practices used by our respondents include rotational grazing, no-till farming, multi-species cover cropping, retention of native plants and reduced fertilizer use. A central tenet of regenerative agriculture is improving soil quality, which goes hand in hand with its ability to store carbon”.

Figure 2: Regenerative and conventional farmers understand why the functions of soil organic matter (SOM) are so important for positive soil health and production outcomes. Source: Peter Grace GRDC research update webinar February 2022.

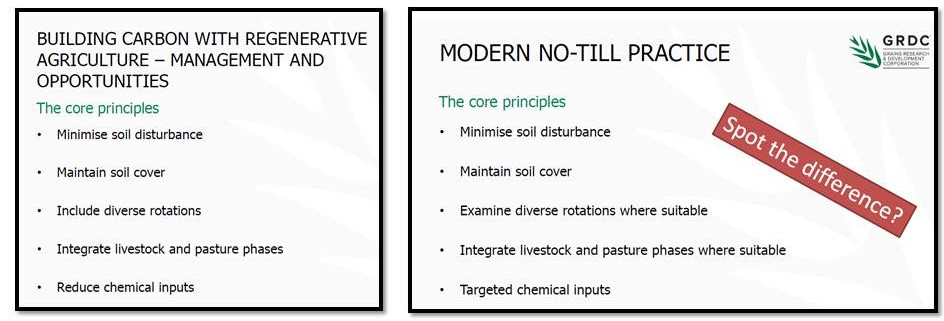

Examining other aspects of regenerative agriculture practices Farrell said that while they are not prescriptive like the rules of certified organic and biodynamic systems they have five key cropping practices:

• minimum soil disturbance

• stubble retention

• diverse rotations (including cover crops)

* inclusion of livestock in the system

• a reduction in synthetic inputs (including pesticides and fertilisers).

“In Australian broadacre agriculture, minimum soil disturbance, through the adoption of no-till (NT) and stubble retention, have been almost universally adopted over the past 20-30 years, whilst diverse rotations are increasingly seen as a best practice way to manage disease and the risk of seasonal variations. Thus, the first three RA practices, far from being something new, are widely adopted conventional farming practices , with the general presumption that amongst other agronomic benefits, SOC stocks also increase,” he said.

The Textile Exchange agrees “there is no standardised definition of regenerative agriculture” but believes programs (on-farm) should include :

• Minimize and ideally eliminate external inputs; maximize on-farm inputs

• Integrate livestock whenever possible given the cropping system

• Reduce tillage to preserve the life in the soil (by utilizing no-, minimal-, or conservation-tillage)

• Aim for and monitor a broad and holistic set of outcomes including soil health, biodiversity, animal welfare, social justice, and the economic well-being of farmers and communities.

There is a standout difference between what the Textile Exchange believes regenerative agriculture embraces and conventional agriculture does not, that is, to farm by eliminating external input like fertilisers and pesticides and avoid being an “extractive agriculture system”. The extractive description of conventional agriculture is mentioned 21 times throughout the Textile Exchanges Landscape Analysis.

At one point it states “Regenerative agriculture is an opportunity for investment in a fundamentally different system that moves beyond the current extractive model”. Further on it makes its number one recommendation: “Companies should approach regenerative agriculture as an investment in a fundamentally different system that has multiple co-benefits, not a variation on the predominant extractive model.”

But there is no definition of what the extractive model is. Does it mean conventional agriculture removes elements, carbon, organic matter, biodiversity from the soil, or in other words degrading it? If so that doesn’t fit at all well with Figure 2.

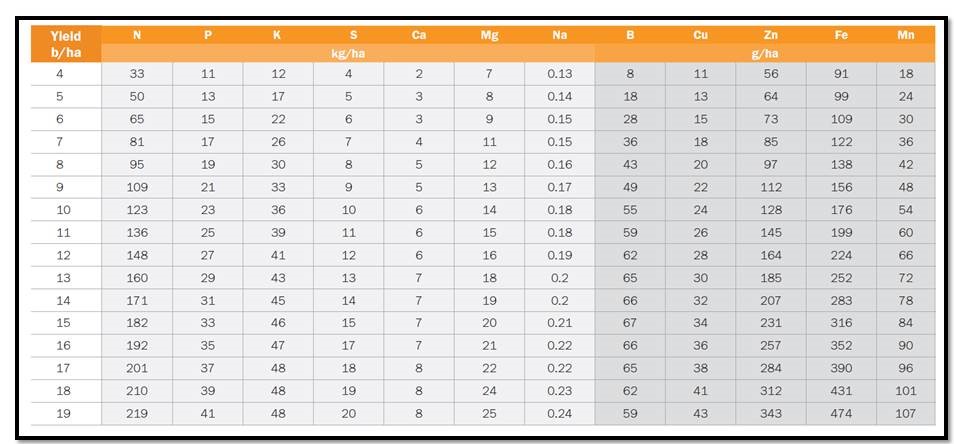

The problem with attempting to distinguish regenerative agriculture from conventional agriculture on the basis that it is not extractive is that the science doesn’t stack up to do so. All farming is extractive once any fibre or food leaves the farm because all products contain major and trace elements in their chemistry. Table 1 shows how much nutrient is removed in raw cotton.

As for wool, a 5kg fleece removes approximately 2 grams of phosphorus, 10grams potassium and 20 grams of sulphur.

Cotton and wool are processed off farm and turned into textile, sold to consumers around the world and eventually disposed of with virtually none of their constituent nutrients returned to the farm of origin – that is extractive. Apart from nitrogen the only way farming can continue to produce fibres and food is to import the elements lost in the products by applying fertilisers. If this does not happen the soil is being mined, will loose soil organic matter and the functions SOM supports (figure 2).

When it was pointed out that all farming involves extracting nutrients out of the soil co-author of the Landscape Analysis and Textile Exchange’s climate and strategy director Beth Jensen said “We used the term “extractive agriculture” and the reference to this being the current dominant model to reference the large factory farming operations (i.e. Cargill, JBS, etc.) that currently comprise the majority of the global food supply. I can see how a more nuanced view might consider any farming operation as extractive in some way, but that was not our intent.”

Table 1: The total amount of each nutrient removed per hectare for a range of cotton crop yields in bales per hectare: Source: Cotton RDC Nutripak.

Farrell pointed out that regenerative agriculture has an issue with external inputs and does not address the implications of not replacing them, table 2.

Table 2: Mark Farrell’s comparison of regenerative agriculture’s core principles for cropping versus modern no-till conventional practice core principles. Source: Mark Farrell, GRDC Crops Research Update February 2022.

“Reducing the amount of synthetic inputs is a far more complex topic, separable into two distinct categories: agrichemicals for weed, pest and disease control; and synthetic fertilisers,” he said.

The most obvious issue for regenerative agriculture practice discouraging agrochemicals is weed control with no-till sowing crops and pastures. Conventional practice has substituted herbicides for tillage to maintain soil quality and health by not damaging soil structure and aerating it subsequently achieving all the co-benefits no tillage has in figure 2. Regenerative agriculture also advocates for no-till sowing but apart from cover crops and stubble retention does not address how weeds are to be controlled without negative impacts of ploughing on soil quality and health.

This Landscape Analysis is similar to many other advocates of regenerative agriculture when it comes to using chemical inputs with rhetoric confusing farmers who have to deal with the practical issues relating to successful farming embracing climate change. The Textile Exchange’s Jensen notes “on a global scale, we need to reduce the amount of synthetic fertilizers/pesticides being used, as this is a significant contributor to greenhouse gas emissions – with the recognition that full elimination will not be possible in certain farming systems and geographic regions.”

The problem with this response is that textile brands and consumers are oblivious of farming’s practical issues with for example weed control or livestock health, they only hear “eliminate chemical input” and failing to do so is degrading environment and food’s nutritional value. It is why such an Analysis in support of regenerative farming without sufficient context around preferred methods of farming has potential for serious unintended consequences for future food and textile production.

Jensen also contends the “…takeaway promoted throughout the (Regenerative Farming Landscape Analysis) report is that there is no single “checklist” of practices across systems and regions – each individual landscape and production system is unique and will require specific practices to ensure the system is balanced.”

This is an important proviso statement and could have been highlighted at the start of the Landscape Analysis.

Figure 3: One of the soil health anomalies associated with adopting regenerative agriculture’s no or limited herbicide use is how to control weeds without damaging soil quality. Using herbicides weed are controlled with minimal tractor greenhouse gas emissions and no soil disturbance. Weedseeker technology also minimises the amount of herbicide applied per hectare (top). Without herbicides weeds may need tillage with its negative impacts associated with high tractor greenhouse gas emissions, soil structural decline, and soil organic matter and soil carbon loss (bottom).

As for the Textile Exchange advocating for no fertiliser this usually refers to no chemical fertilisers but purist regenerative agriculture advocates also suggest no organic fertiliser as well. The latter stance may be explained by the fact the only commercially available significant sources of nutrient rich organic fertilisers are intensive animal production farms such as cattle feedlots, and housed piggeries and poultry where manure can be collected. Such farms are considered “industrial or factory” livestock enterprises and are not acceptable.

Figure 4: Beef cattle feedlots and other intensive animal industries are the most important and available sources of organic manures which replace nutrients exported off farm in fibres and foods. The manure is an important soil quality ameliorant and organic matter source for soil biology. An unintended consequence of advocating for removal of intensive animal agriculture is the loss of this important soil ameliorant.

On the other hand regenerative agriculture farmers prepared to use organic fertilisers to replace nutrients exported off-farm in cotton, wool, and meat products are in-effect endorsing the fact that intensive livestock raising is an important component of the food industry. It provides conventional, organic, and regenerative farmers with a supply of nutrients and organic matter to re-supply soil with those exported off-farm.

The Agriwebb 2022 farmer survey report highlights that less fertiliser use is somehow better for profitability and the environment. “In good news for the wallet and the environment, producers are managing to reduce their inputs of both feed and fertilizer. It’s one of the most widely adopted holistic practices noted in this report survey.”

Without giving context to achieving soil nutrient balance with fertilisers, such broad recommendations are likely to have significant negative consequences for both profitability and soil quality and health as demonstrated in figure 2.

Farrell addressed the regenerative farmers aspiration to reduce synthetic (chemical) fertiliser inputs particularly nitrogen (N).

“The ‘elephant in the room’ when it comes to N export or loss from farming systems is actually the amount that is removed in the produce itself. A comprehensive study found that the majority of properties studied in southern and eastern Australia were net exporters of N from the crop alone. If other losses (particularly N2 from denitrification, which is the least quantified) are also present in the system, this could contribute to substantial N mining in the medium to longer term, with concomitant impacts on SOC stocks.

“It is important to recognise the intrinsic links between SOC and N — the majority of N in soils is chemically bound to SOC in the form of SOM. If synthetic N inputs are reduced and the balance is not replaced via N fixation, N will be ‘mined’ by the crop from SOM, resulting in a loss of SOC.”

The critical point he makes about soil health management which builds SOM and subsequently SOC is that their stocks are a function of inputs and outputs. “it is primarily plant growth that results in C inputs to soil, and there are several means of manipulating this to improve the likelihood of increasing C stocks. Also, as C stocks increase over the longer term, it is likely that the ability of the soil to supply N through the mineralisation of SOM will also increase, provided that the N balance remains positive.”

Figure: Regenerative Agriculture is constantly being projected to farmers, politicians and consumers as new and alternative suite of methods for maintaining or improving soil health that are not available through agricultural science. Source: NASAA Organics, South Australia 2021,

Farrell said that to ensure SOM and nitrogen levels are maintained and increasing “the simple equation is that inputs need to be greater than exports and losses. There are several ‘levers that can be pulled’ on both sides of this equation, but it is important to understand that for the most part, the soil C and N cycles are intrinsically linked, as most N is bound in SOM, and the effectiveness of management efforts will be strongly influenced by climate and soil type. Approaches that increase N inputs will both reduce N-mining and increase C inputs through greater plant productivity.”

He said that is possible to achieve a neutral or positive nitrogen balance using regenerative agriculture principles that exclude synthetic fertilisers and thus build SOM, but this requires:

* 50% of rotation in pasture legumes or winter cover crops, or

* affordable access to organic inputs to balance nitrogen removed in grain. Unless the farm is close to livestock manure waste streams this would be cost prohibitive.

The science surrounding building SOM for a host of co-benefits as explained by Farrell puts the Textile Exhange’s Regenerative Farming Landscape Analysis in a difficult position to achieve on-farm outcomes around improving soil quality and health without external inputs while also being a profitable raw material producing business.

What will be interesting to find out how the aspiration to “Minimize and ideally eliminate external inputs” relates to its Responsible Wool Standard. The current standard, V2.2, make no mention of regenerative agriculture but with respect to fertiliser use on pastures and crops states “Desired outcome:Farmers use the minimum amount of inputs to meet the nutritional needs of their land to maintain their carrying capacity.”

This seems to be a clear recognition that farming is extractive and the nutrients removed need to be replaced from outside sources. It contradicts the Landscape Analysis’ assumption that farming should not be extractive.

Despite Jensen’s statement “…each individual landscape and production system is unique and will require specific practices to ensure the system is balanced” it seems a possibility the Textile Exchange will move its textile standards towards being organic. “Ultimately, organic and regenerative should not be considered as competing concepts—there is much that unites them, and both movements can build on and learn from one another along their shared path to achieving equitable and restorative agricultural systems,” the Regenerative Agriculture Landscape Analysis states.

It also suggest that companies buying natural fibres encourage farmers to transition to regenerative agriculture in much the same way as farmers transition into organic certification. This transition out of using herbicides and pesticides should be time limited so that it “lays out a clear pathway to transitioning away from the extractive agricultural system and towards a more holistic regenerative approach.”