Environmental baselines and the myth of lost Eden

By Ted Lefroy

Writer, poet and farmer Wendell Berry said of the first European farmers in North America that they came with vision but not with sight. They came with the vision of former places but not the sight to see where they were. Instead of adapting themselves to suit the land they adapted the land to suit their memory of former places. They did not know what they were doing because they did know what they were undoing. The more we learn about the deep history of this continent, the more those sentiments ring true for Australia.

Three recent books on Australian environmental history have renewed debate about the sustainability and even the legitimacy of Australian agriculture. Bill Gammage’s The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia (2011), Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu Black Seeds: Agriculture or Accident (2014) and Charles Massy’s Call of the Reed Warbler: A New Agriculture, A New Earth (2017) all offer new ways of seeing Australia and the way it is and has been managed. In a recent essay in The Conversation, Tony Hughes-D’Aeth author of Like No Place On Earth: A Literary History of the Wheatbelt (2017), proposed that the common purpose of the authors of those three books was to locate a new environmental baseline as a standard or measure against which contemporary agriculture should be judged (Hughes-D’Aeth 2018). He suggests this search extends the theme of earlier national and regional environmental histories including Tim Flannery’s The Future Eaters (1994) and Eric Rolls’ A Million Wild Acres (1981).

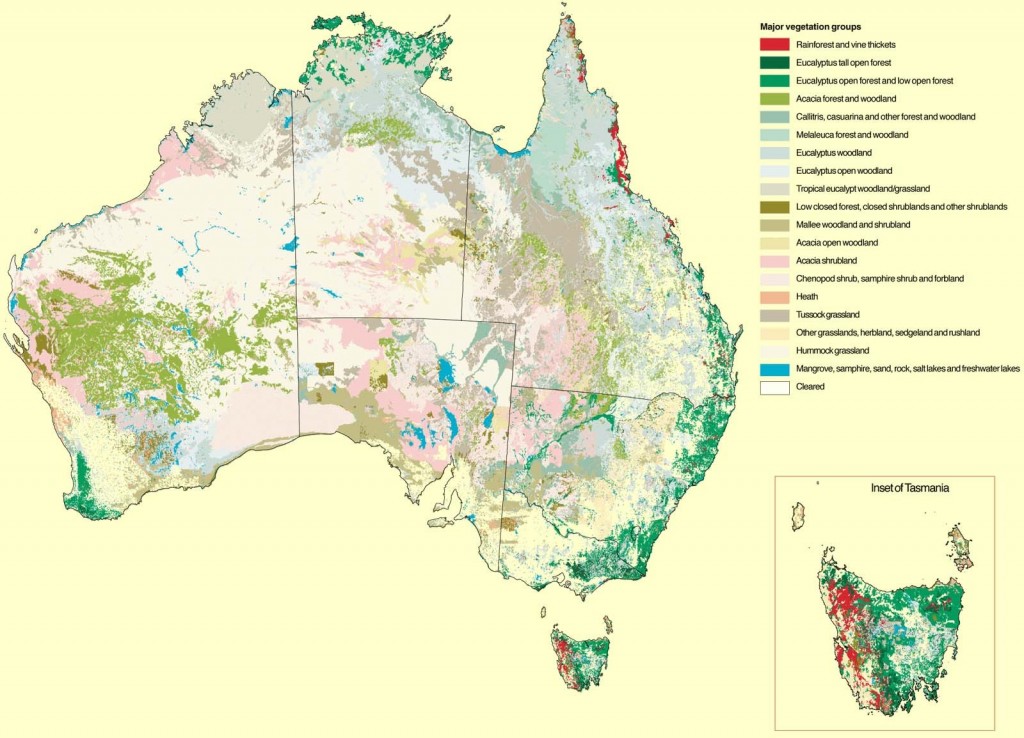

Figure 1: The story of Australian agriculture always has and always will be regional.

The historical sciences however, ecology and archaeology in particular, suggest there are two reasons why the search for such a baseline is illusive.

The first reason is time as baselines are constantly shifting. To hold agriculture to a standard frozen in time ignores its evolutionary history as the interaction between culture and nature. To do so can be a convenient way to blame another time or other people for the problems of agriculture, but the challenge is which time to choose?

Australia has at least six candidates for a lost Eden, take your pick: Australia before humans; during the time of the Pleistocene hunters (before and after the extinction of the megafauna); the first proto-farmers sometime around 6,000 years ago; 1788 before the invasion of the yeoman farmers; or before industrialisation when a litre of fossil fuel substituted for 100 hours of labour triggering dramatic landscape change and consolidation into fewer and larger farms.

The second reason is space. The story of Australian agriculture always has and always will be regional. There are as many forms of agriculture as there are ecosystems from cool temperate Tasmania to the true tropics. When Bruce Pascoe describes in Dark Emu Aboriginal farmers harvesting grain, living in villages and constructing the first stone structures in human history he is not telling one universal continental story.

In Billy Griffiths’ history of Australian archaeology Deep Time Dreaming: Uncovering Ancient Australia (2018), he describes a series of attempts to arrive at continental generalisations about Aboriginal technology, art and culture that all failed because the story of adaptation is intensely regional.

In her review of Bill Gammage’s book The Biggest Estate on Earth, archaeologist Sylvia Hallam (2011) acknowledged that book’s great contribution to our understanding of Australia’s deep history but warns against a continental view of fire as that story is also local and highly variable as she showed in her study of fire in south western Australia (Hallam 1989).

Compared to Aboriginal land management, the project to transplant agricultural technology from the northern hemisphere to Australian soils and climates has been a short, sharp and varied story of success, failure, adaptation and invention. And it continues. The attempt to adapt to the only continent where plants and animals have been shaped more by variation between years than within as Flannery points out in The Future Eaters, the land ‘of droughts and flooding rains’, is a work in progress.

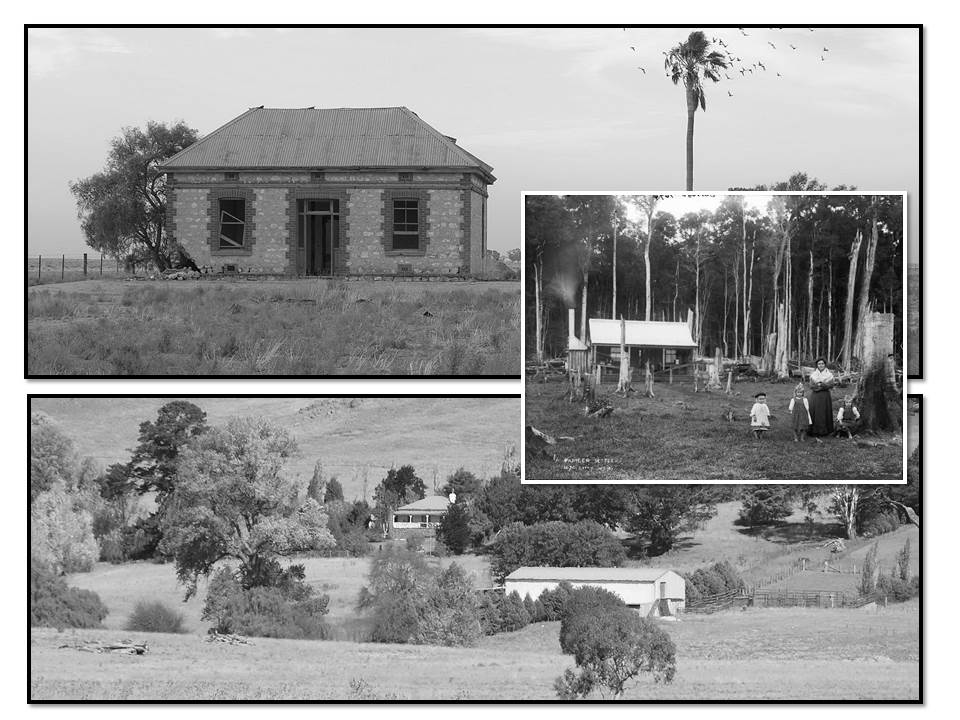

Figure 2: The project to transplant agricultural technology from the northern hemisphere to Australian soils and climates has been a short, sharp and varied story of success, failure, adaptation and invention. Photos: Patrick Francis(top Mid North SA and bottom New England NSW), Inset: Power House Museum.

So far this effort has spawned Permaculture as a worldwide movement along with local heroes including PA Yeomans’ Keyline Farming, Peter Andrews’ Natural Sequence Agriculture, Alex Podolinsky’s adaptation of biodynamic farming, Charles Massy’s elegiac advocacy of Holistic Grazing Management and the largest area of organic farmland in the world, more than 22 million hectares according to market researcher IBIS World (2017)

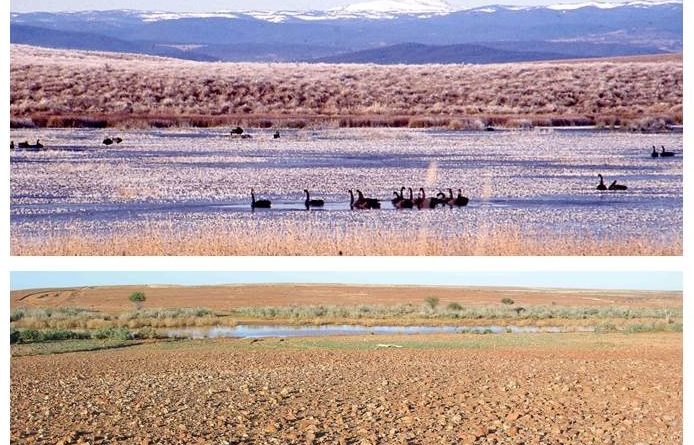

Figure 3: There are many Australians who remember the bush before the plough. Photos: Patrick Francis Left: Pilliga forest central west NSW; Moutain ash forest Otways Victoria.

In his essay Hughes-D’Aeth describes Australian agriculture as ‘sustained plunder’, ‘a form of psychosis’ and ‘a religion’. Maybe that view stems from the fact that unlike Europe where there is no one alive today who remembers the forest before the farm, there are many Australians who remember the bush before the plough. Perhaps no coincidence then that it was an Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht who coined the term solastalgia, literally comfort-pain, the home sickness you have without leaving home when the world around you changes, in his case a response to drought in his home state of NSW.

The most recent attempt to adapt agriculture to Australian environments is slow in human lifetimes. And for an overwhelmingly urban nation we do tend to overly romanticise our relationship with the bush. But does that make agriculture a religion? Only as long as we cling to the myth of a lost and perfect Eden.

Find out more:

Ted Lefroy is Adjunct Professor Tasmanian Institute of Agriculture, University of Tasmania. A shorter version of this opinion piece was published in 2018 in the Australasian Journal of Environmental Management.

References

Flannery, Tim (1994) The Future Eaters. Reed Books, Chatswood.

Gammage, Bill (2011) The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia. Crows’ Nest NSW, Allen and Unwin.

Griffiths, Billy (2018) Deep Time Dreaming: Uncovering Ancient Australia. Carlton VIC, Black Inc.

Hallam, Sylvia (2011) Review of The Biggest Estate On Earth: How Aborigines made Australia. Australian Aboriginal Studies 2: 123-6.

Hallam, Sylvia (1989) Fire and hearth: A study of Aboriginal usage and European usurpation in SW Australia. Crawley WA, UWAP.

Hughes-D’Aeth, Tony (2017) Like No Place On Earth: A Literary History of the Wheatbelt. Crawley WA, UWAP.

Hughes-D’Aeth, Tony (2018) Dark Emu: The Blindness of Australian Agriculture. The Conversation, June 15 2018, accessed 9 July 2018 https://theconversation.com/friday-essay-dark-emu-and-the-blindness-of-australian-agriculture-97444

IBIS World (2017) Organic Farming: Australia market research report, accessed 9 July 2018 https://www.ibisworld.com.au/industry-trends/market-research-reports/thematic-reports/organic-farming.html

Massy, Charles (2017) Call of the Reed Warbler: A New Agriculture, A New Earth. St Lucia. QLD, UQP.

Pascoe, Bruce (2014) Dark Emu Black Seeds: Agriculture or Accident. Broome, WA, Magabala Books.

Rolls, Eric (1981) A Million Wild Acres: 200 years of man and an Australia forest. Melbourne, VIC, Nelson.

Thanks for mentioning solastalgia. I have forwarded the idea of sumbioregions in my book ‘Earth Emotions’ (2019). In it I argue: “To give expression to this emergent idea I define a ‘sumbioregion’ as an identifiable biophysical and cultural geographical space where humans live together and engage in a common pursuit of the nurturing, re-establishment and creation of new symbiotic interrelationships between humans, non-human organisms and landscapes. More fine-tuned self-sufficiency within sumbioregions ipso facto means less global destruction. More emotional ‘grounding’ in the local, and people will be more secure. Terroirism just might also be a counter to terrorism and war. More democracy within regions will phase into sumbiocracy, as that which is inherent and endemic to a sumbioregion is perceived to be valuable and must be conserved. ” I hope that idea comes close to what you are saying about the uniqueness of ‘space’. I agree that generalisations that are continental-wide will miss the nuances of place (spaces that have been given cultural meaning).