Livestock farming tips for beginners

By Patrick Francis

In April 2017 I was asked by the Upper Deep Creek Landcare Network to present a brief insight into important considerations when deciding on running livestock on a lifestyle or absentee owner farm in the Macedon Ranges Shire. Because of its proximity to Melbourne, many new landowners either commute daily to jobs in Melbourne or live in Melbourne and visit their small blocks on weekends and holidays. Added to this most of these landowners have little or no prior knowledge of animal husbandry, pasture management, and environmental management.

A final complication is much of the farm land in the Macedon Ranges Shire (and many other shires) has seen a significant demographic change since the 1970’s where family farms dominated, to the situation where many of these farms have been subdivided into smaller blocks for part-time and lifestyle livestock enterprises. Many of the smaller farms have been neglected for decades as far as soil health, pasture health and ecosystem function health is concerned.

The result is a shire with the majority of grazing land dominated by low soil fertility, high soil acidity, unproductive pasture species, and often poor ecosystem functions, particularly biodiversity. As climate change increases the incidence of “boom – bust” rainfall cycles, many small landholders are coming under increasing mental stress coping with livestock enterprises and ecological functions they have little knowledge about. While local landcare groups provide owners with an important source of knowledge for environmental improvement and where to find assistance, information about animal husbandry in the shire is less available. Here are the livestock alternatives key points I made at the Information Session.

The Macedon Ranges Shire has a reasonably reliable rainfall, coupled with moderate summer temperatures, but cold winters with high wind chill, to support a wide range of livestock enterprises. Coupled with its proximity to Melbourne, boutique livestock businesses can develop market outlets for products which a small but increasing percentage of consumers are looking for, that is livestock products with credence values. That means products with animal husbandry, animal welfare and environmental welfare attributes that exceed those provided with mainstream, professionally farmed meats, eggs, and wool.

Animal welfare standards

All livestock owners have a legal responsibility to look after the welfare of the livestock under their ownership. In the past, such requirements were detailed in sheep and cattle “Codes of Practice”, but they have been recently changed to the adoption of “Standards & Guidelines”. The difference being there are now some “must do” practices as opposed to “should do” practices. If the must do practices are not adhered to then the livestock owner may be prosecuted.

An example is lamb tail docking and castration which should be done between 24 hours of age and 12 weeks of age and must not be performed after 6 months of age without pain relief.

All potential livestock owners should read the sheep and cattle Standards & Guidelines before making a decision on what enterprise to adopt.

Empathy welfare

While the “Standards & Guidelines” detail legal requirements, livestock farmers can go much further in looking after the welfare of their animals, I call this empathy welfare. It has particular value for small livestock enterprises because once an empathy bond is developed, livestock husbandry is simpler and less time consuming and it contributes to the story more discerning food consumers are looking for.

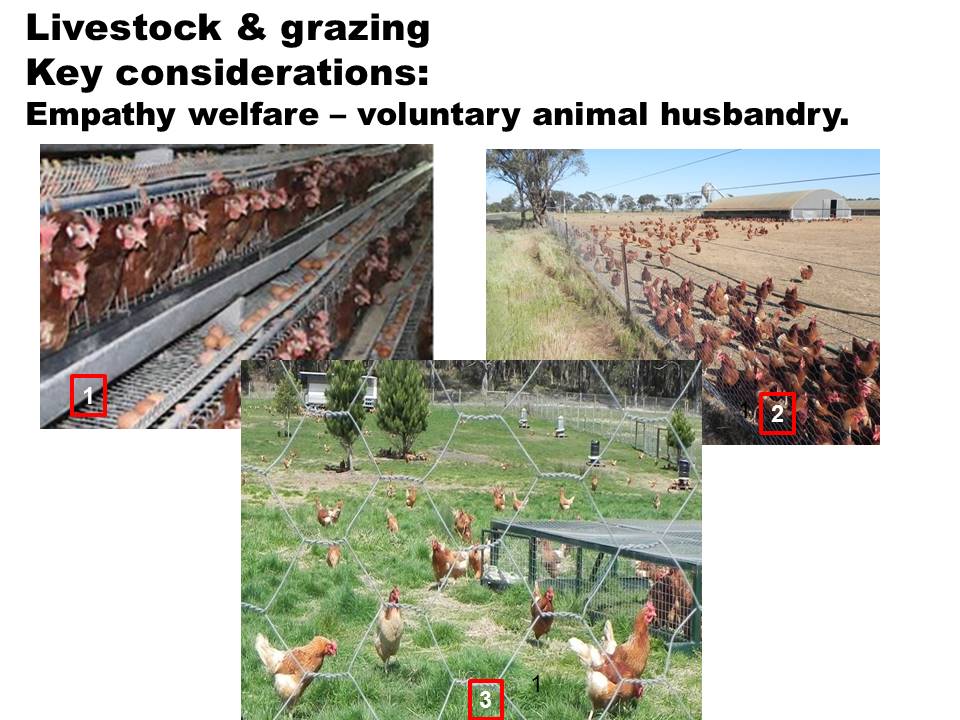

The most obvious example of livestock empathy welfare is shown with layer poultry in Figure 1. All three images are of legal layer poultry husbandry, but empathy with the birds increases as they are removed from cages, move into free range with bare pens, then into free range with pasture quantity maintained year round using rotational grazing. While the law considers all three systems are acceptable on animal welfare terms, it is system three which an increasing percentage of consumers prefer to source their eggs from and pay extra for additional costs incurred developing empathy for the livestock.

Figure 1: While all three systems of poultry farming are legal, empathy welfare is far higher is system three than the other two systems.

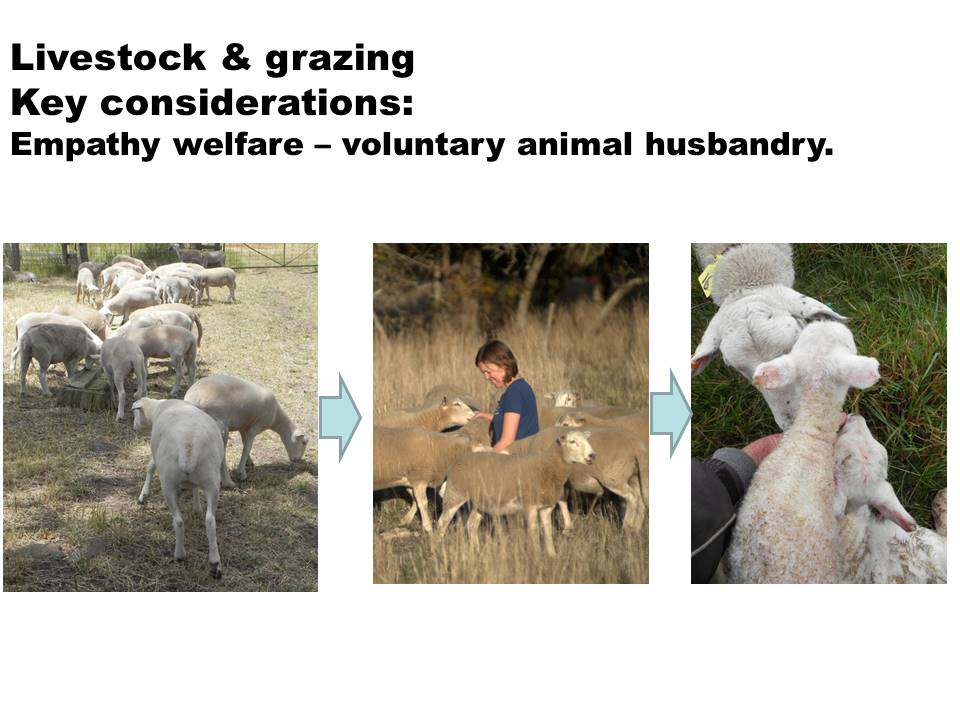

A more subtle example of empathy welfare is shown in Figure 2. On Moffitts Farm we often “yard wean” lambs. This involves confining them in a large yard with clean water and ad lib access to high quality pasture silage for up to five days. Each day I take high quality lucerne chaff in buckets into the yard and put it out in open troughs. This is done three to four times a day. The most inquisitive lambs come up to the troughs to see what’s in them, the lucerne chaff is highly attractive feed. With constant repetition of taking feed into the yard, the lambs soon realise two things, firstly, there is no need to run away from a human, and secondly the human is associated with feed they want to eat.

By the fifth day of this procedure, most lambs run to me at the yard gate and have no fear of human presence. They follow me closely and it is difficult to put the lucerne in the feeders. A bond has been developed between the human and the sheep.

This bond is continued once the lambs are moved from the weaning yard into fresh high quality pasture paddock. From then on the “leader” lambs will still come to the human holding a bucket of lucerne chaff and eat out of the bucket, they bring all the other lambs in the paddock with them.. Combine this training with weekly paddock rotation and the lambs become keener to follow the human to the next fresh paddock of pasture. After a few weeks a bucket is no longer needed, the lambs come when called.

The benefits to part-time and absentee farmers are enormous. Livestock movement from one paddock to the next is quick and stress free. No dog, motor bike or ATV is needed to muster the flock into the next paddock or even into laneways and into yards. In times of emergency, particularly an approaching fire, stock are easily moved into a safe paddock.

But there are many more spin-offs for the empathy developed with this training and grazing management. As the lambs transition to breeding ewes, lambing supervision becomes a stress free and rewarding procedure. In trained flocks it is possible to walk quietly among lambing ewes without the fear of them taking fright and leaving lambs. We can walk up to new born lamb check they are healthy, weigh them, identify sex, while the ewe stands beside them. We actually allocate a Maternal Behaviour Score based on how close the ewe stands while her lambs are being examined. A one score means the ewe stands next to the human, a five score, the ewe runs away as far as possible. All our ewes are now one and two scores. We use this score as part of our ewe selection criteria.

Figure 2: Developing empathy with livestock has all sorts of practical benefits for the owners, the livestock and the farm environment; it is a story an increasing percentage of consumers are looking for.

Associated with this empathy is the ability to actually take a ewe with lamb(s) with a possible health issue out of the paddock by herself day or night. The typical example here is an extreme wind chill and rain night in August and below average birth weight lambs. Despite the wind protection offered by high pasture, the wet can threaten a below average birth weight lamb’s life. If considered necessary a ewe with her lambs can easily be moved into an adjacent shed for overnight protection (usually let back into the paddock the next day).

A further advantage of empathy built up between lambs and humans relates to the impact of stress on meat quality. Low stress livestock handling has a positive impact on lamb eating quality. We contend our lamb’s carcase characteristics such as meat colour, fat colour may be little different to conventionally farmed lambs, but our lamb’s eating quality is exceptionally high based on taste tests. There are a host of biochemical impacts taking place in meat pre and post-mortem. The less stress felt by lambs, given the same carcase weight and fat thickness, the higher meat eating quality.

The same empathy impacts we achieve with sheep were also achieved in our breeding cattle herd. But a word of caution with cattle, the animals are larger, stronger and have potential to cause injury even when empathy has been built up. Empathy must be combined with animal behaviour knowledge and anticipation to ensure safety at all times. Docility can never be taken for granted as animal instincts can sometimes override empathy – the classic example is handling a new born calf. The mother’s instinct to protect the calf can outweigh any empathy previously developed and the human can be charged. The same instinct versus empathy breakdown can happen with bulls and rams. We never encourage patting/scratching replacement ram lambs because as they become bigger and sexually mature a “game” involving bunting can lead to serious injury and it can happen out of the blue.

Other livestock ownership considerations

Outside of welfare there are a host of other factors potential livestock owners should consider when deciding on what sort of animals to buy.

Time required – breeding stock v dry stock.

For small farm owners who are time short or who do not live on the property, dry stock as opposed to breeding stock are preferable. It is feasible to purchase female animals but not join them for breeding until circumstances change and more time and supervision is available.

Time to supervise breeding animals at calving and lambing is not negotiable. During this period daily inspection is required. If the owners are not available then they must engage a neighbour, friend or local worker to do so.

Figure 3: With breeding stock daily inspection is required during lambing and calving. Photo: Patrick Francis.

After the lambing and calving period the herd or flock needs regular inspection (every second or third day) for at least three months as young animals are prone to: mishaps such as getting through a fence and being unable to get back to their mothers; diseases such as scours, and attacks from predators such as foxes or domestic dogs.

Lambs and calves also need vaccination against clostridial diseases at around three to six weeks of age. Males are castrated at the same time. Electronic identification ear tags are also usually applied at this time. Electronic identification of cattle has been mandatory for cattle for many years and has been introduced by the Victorian government for all sheep born from 2017 on.

Weaning calves and lambs is another time consuming component of owning breeders. The method I advocate is yard weaning where the lambs/calves are confined to a well fenced stock yard for 4 to 7 days. Two to three times a day the animals are fed an attractive ration such as lucerne chaff in troughs to develop empathy between stock and humans. They also have ad lib access to pasture silage or high quality pasture/clover hay in a roll feeder.

An alternative weaning method is paddock weaning, its major drawback is calves and lambs will wander excessively for two to three days trying to find their mothers and can escape through fences onto roads, or into neighbours paddocks or back with their mothers. There is little opportunity for developing empathy with the weaners. When we utilise lamb paddock weaning we always include two leader wethers with the lambs. These weather come when called and the lambs follow them. The lambs soon learn from the leader wethers to follow humans and not be afraid.

A third weaning method is natural weaning where calves and lambs stay with their mothers until the cow or ewes stops lactating. Major issues of this method are welfare of the ewe and cow if she loses too much weight while continuing to feed her progeny for an extended period – greater than 14 weeks for ewes and greater than eight months for cows. There is also an issue with keeping female young which have started oestrus cycles from joining with bulls/rams.

Economy of scale – breeding, transport, marketing

Economy of scale of livestock enterprises is an issue particularly associated with breeding cattle, livestock health, and marketing animals. For instance, a small farm with 15 to 20 cows will need to buy or lease a bull which is normally capable of breeding with 50 to 60 cows. So bull cost per calf is immediately two to three times the cost of that in larger herds. Similarly, safe facilities are needed irrespective of having one cow or 100 cows. So small herds need a safe cattle crush and sturdy yards just the same as large herds.

When it comes to marketing weaner calves or older progeny, a small herd may have 5 to 10 animals at a target market weight at one point in time, but transport to markets is costly as trucks usually carry two to four times that number. Even private sales for small lots are less attractive to buyers because of transport costs.

Farming with dry cattle helps overcome economy of scale issues as larger numbers can be purchased and sold together. For instance, 15 breeding cows with 15 calves eat the equivalent pasture over 12 months as about 40, 250 – 500kg liveweight steers or heifers.

Breeding sheep have fewer issues with economy of scale as more ewes can be run per hectare which makes ram purchase more cost effective. The 15 breeding cows (with 15 calves) eat about the same amount of pasture over 12 months as 45 breeding ewes (with 60 lambs – small flocks should average about 130% lambs weaned with careful management). Access to markets is better as the owner can transport lambs in a trailer. Also equipment to handle sheep is far less expensive than that required for cattle so is more effective to buy even for small flocks.

However, sheep which need shearing have economy of scale issues associated with facilities for undertaking shearing, crutching and marketing the wool. These are eliminated if shedding breeds of sheep are purchased rather than wool sheep.

Another economy of scale factor relates to buying animal health products which have use by dates. Pack sizes can be too large for small herd use within the use by date.

Facilities – sheep v cattle, safety and technology

Cattle are strong animals and where sorting and restraint are needed sturdy yards and crush are mandatory irrespective of herd size. Work place health and safety gives a requirement for stock owners to have facilities which minimise the opportunity for accidents happening. Legal liability associated with accidents in sub-standard facilities needs to be kept in mind. The liabilities extend to family members, friends and neighbours as well as professionals like veterinarians or livestock truck operators.

Figure 4: Irrespective of the size of a cattle farm, facilities must be sufficiently robust for safe handling when management such as pregnancy testing, ear tagging etc is required. Photo: Patrick Francis.

Facilities to hold, sort and handle sheep must also be safe but their scale is much smaller and less expensive than those for cattle.

There is a technological component of facilities required for sheep and cattle and that relates to electronic identification. Across Australia all cattle movements off farm must be recorded via the National Livestock Identification Scheme. In Victoria from 31 March 2018 onwards this also applies to all sheep movements off farm. Often small landowners find it simpler to buy livestock from neighbours or friends, but it is the purchaser’s responsibility to notify NLIS of the transaction. This means the purchaser must read each electronic tag and send the data to the Scheme. The most practical way to read these tag is with an electronic reader which costs in the order of $1500. The alternative is to buy through livestock agents who will do the reading for a fee. Agents also require the vendor to pay a commission on the sale. While a reader might be too expensive for one landholder, it is possible for a group or club of landholders to share the purchase of a reader. (For more details about sheep and cattle owners responsibilities for reporting livestock movement off the farm see Appendix 1).

Figure 5: In Victoria all cattle and all sheep (born from 2017) must be fitted with and electronic National Livestock Identification Scheme tag. A small livestock farmer might not justify the purchase cost of a tag reader but a group of owners could. Photo: Patrick Francis

Another technology small farmers benefit from but are disadvantaged due to herd/flock size is the use of electronic weighing. Small farmers need to weigh livestock throughout the year for a range of management reasons. Given they usually have a poor ability to estimate live weight, scales are important to know live weights for administering the correct dose of animal health products such as drenches; to find out if animals are maintaining, losing or gaining weight; and for marketing livestock at processors desired weights or in the case of store stock when selling or buying on a price per kilogram live weight basis.

A basic weigh bar set and reader will cost around $2200 and weigh crates add around another $1500 for sheep and $2500 for cattle. This is another opportunity for club members to join together to buy and share weighing equipment.

Fencing – sheep v cattle, conventional v electric

Fencing is a major and critical infrastructure cost for all landowners. There are four main aspects:

- Stock security on the farm – that is livestock cannot escape from the paddock they are put in.

- Farm security or biosecurity so stock from other properties don’t access your farm and possibly bring diseases in with them.

- Farm security against unwanted feral and pest animal intrusions. This relates in our area particularly to foxes, rabbits, kangaroos and in farming areas close to towns, wandering domestic dogs.

- Subdivision fencing for the maintenance of pasture health, soil health and ecosystem functions such as clean water, riparian zone health and biodiversity improvement.

The factors to consider when fencing are:

- Double perimeter fencing for on-farm stock security, prevent unwanted incursions, and biosecurity. Where kangaroo numbers are causing pasture and soil degradation, the perimeter fence can be a 1.8m high exclusion fence, figure 6. Most of the wire companies have particular fence types for this job. While very expensive the initial outlay can be justified to prevent an enormous number of management problems and possibly even neighbour conflicts for years after construction. The second perimeter fence should be approximately 30m inside the exclusion fence. The area in-between is used for remnant vegetation protection or establishment of conservation plantings with or without farm forestry plantings. Keep a 5m gap between rows and fences so slashing for weed control can be undertaken. After plantings are about five years of age the exclusion area can be occasionally grazed instead of slashing. It can be a useful area, particularly for ewes and lambs and recently shorn sheep, if protection against cold weather is needed for a few days.

Figure 6: An exclusion fence with an apron on the bottom is well worth considering for smaller farms. It has been erected inside the old boundary fence. This 1.8m high Clipex fence will prevent incursions from predators such as foxes and kangaroos. Photo: Patrick Francis.

- Conventional internal sheep fences can be simply constructed using prefabricated wire with non-slip knots.

- If weaner sheep are trained to recognise electric fences, a two wire electric fence can work for sub-division fencing. Success of these fences requires a good understanding of sheep and cattle pasture requirements and building pasture banks which ensure animals are nutritionally content behind the electric wire. Development of empathy with livestock is also important for successful electric wire subdivision on small farms. Easily frightened animals will crash through one or two wire electric fences. Newly purchased livestock which have not experienced electric fences before need to be trained to living in paddocks with them. This can be done in a secure yard fitted with an electric wire on an outrigger.

- Conventional cattle fences usually involve six or seven wires and one or two embedded electric wires or an outrigger wire. When electric wires are included, it is not necessary to use barb wire in the fence.

- If cattle are trained to recognise electric fences, a single electric wire can work for sub-division fencing.

- Conservation corridors between paddocks, remnant vegetation restoration and riparian zones need conventional fences and with cattle at least an electric wire outrigger. One single incursion into a new planting up to about five years of age can cause such significant damage to seedlings and small trees that the corridor must be replanted. Absentee landowners have even greater risk of serious damage happening if secure fencing is not in place.

Predator control – foxes, dogs

If considering owning small ruminant livestock, pigs and poultry, then owners need to be comfortable with controlling foxes and in some areas close to towns incursions from wandering domestic dogs.

Fox control is significantly helped with the exclusion fence described above, but even with this these animals have uncanny ability to find a security breech. Without such fencing, fox control is critical component of annual management of small livestock species.

Shooting, baiting with Foxoff (1080) and den destruction are needed in combination to prevent animal losses. To use Foxoff the land owner must have an Agricultural Chemical Users Permit (ACUP) with a 1080 use endorsement. Co-operation of neighbours in controlling foxes on their properties is particularly useful but in our shire is unlikely to happen, mainly because with cattle and horse farms foxes are not an issue.

Figure 7: Fox control must be part of annual management when owning breeding sheep, poultry and pigs. Here a fox seeks out buried 1080 bait. Photo: Patrick Francis.

Guard animals, Maremma dogs or alpaca wethers, are often used as a method of protecting livestock from fox attacks. Maremma’s are not an option for absentee owners as the dogs must be fed. If Maremma’s or even alpacas are used as guard animals their success involves the owner having an empathy with the guard animals as well as the livestock. Without it the guard animals become another animal input to be manage for nine months of the year when guarding is not necessary as we don’t have wild dogs to contend with. With free range poultry and pigs guards dogs are likely to be needed year round.

Intruding domestic dogs are a rare but ever present concern for small ruminant livestock, and free range pigs and poultry. Domestic dog owners are generally becoming more diligent about containing dogs on properties and have legal responsibility to do so. Domestic dog intrusions are best dealt with by the Council ranger. Land owners should take photos and videos of intruding dogs and if possible detain them until the ranger arrives. Implementing an annual 1080 fox baiting program provides neighbours and locals who walk dogs on adjacent roads with a strong deterrent against allowing dogs to wander into paddocks. Neighbours must be notified of an impending 1080 bait program and signs erected on entrances to the property.

Kangaroo control

While most landowners view eastern grey kangaroos as part of the farm biodiversity, for some owners in the Shire their numbers have become so great that they prevent or threaten having pastured livestock on the farm.

Eastern grey kangaroo numbers have increased due to increased areas of suitable habitat created by subdivision of larger farms and owners interest in conservation planting. Between 1960 and 1999 I didn’t see a kangaroo on Moffitts Farm and the adjacent farm land owned by my father. With our planting of conservation corridors and forestry blocks through the 1990s, kangaroos began to appear in the 2000’s. The mid 2000’s coincided with a series of below average rainfall years with failed springs in 2002 and 2006. The drier years meant our holistic managed pastures which retained bulk and green feed during summer months became even more attractive to kangaroos. By 2006 60 to 80 kangaroos were common and pasture viability particularly during summer and autumn was being threatened. In other words, the kangaroos became uncontrolled factors which threatened farm ecosystem functions such as soil health, soil carbon, rainfall retention and the soil food web.

Figure 8: The kangaroo exclusion fence on the perimeter of Moffitts Farm consists of wire netting attached to the existing conventional seven wire fence to prevent small kangaroos pushing through plus three plain wires raising the height to 1.8m. While large males can just about clear this height it is a significant deterrent in itself and it prevents females jumping over. Photo: Patrick Francis.

The underlying cause of the kangaroo population increase is lack of predators to control their population, in fact they have no predators. It’s a scenario expressed decades ago by the famous US ecologist Aldo Leopold who described in his book “A Sand County Almanac” (published 1949) how hunting and elimination of wolves (in order to protect livestock) in some parts of the US allowed deer populations to explode which in turn caused overgrazing and subsequent degradation of natural habitats.

Leopold was not the first person to recognise the impact of eliminating predators on ecosystem functions. In the book “Old Melbourne Memories” published in 1896 western Victorian squatter Rolf Boldrewood describes how removal of dingoes to prevent attacks on calves , led to an explosion of kangaroo numbers which in turn increased grazing pressure on native pastures which meant feed available for sheep and cattle was seriously decreased.

“Though he killed an occasional calf, the wild hound did good service in keeping down the kangaroo, which, after his extinction, proved a far more expensive and formidable antagonist”, Boldrewood said.

This year a study by Associate Professor Mike Letnic, The University of New South Wales, has found dingo controls have resulted in a boom in kangaroo numbers, with more wide-reaching environmental effects than previously thought. He said the impact extended beyond the implications for other flora and fauna of the region.

“What we found was that where the grazing by kangaroos was very heavy, the amounts of phosphorous, nitrogen and carbon in the soil were depleted. However, in parts of the landscape where dingoes were still active, kangaroo numbers stayed low and the country was not under the same amount of grazing pressure ,” Letnic said.

Another relevant point Letnic made was that the degradation due to kangaroo population increase was not just happening on farms grazing livestock, it was also happening in national parks.

“This is happening even in country where there are no sheep,” he said.

For property owners in this shire wishing to control excessive kangaroo numbers on their land (mobs of more than 20 animals visiting pastures daily), there is only one, long-term, workable solution – exclusion fencing. Constant scarring or even shooting (after obtaining a permit) is of no use, especially when there is adjacent habitat or neighbours who are happy to have uncontrolled numbers on their farms.

On farms where large kangaroo herds graze from dusk to dawn there is little scope for pasture improvement using species like lucerne, chicory, and summer active tall fescues and cocksfoots. Pasture species diversity will decline as constant grazing gradually kills the more palitible plants leaving behind bare ground and the grazing tolerant, non-productive types such as bent grass, sweet vernal grass, onion grass, and annuals such as capeweed, silver grass and barley grass.

In the worst cases of kangaroo overgrazing, paddock ecosystem functions degrade mainly because there is insufficient pasture herbage to protect the soil food web, prevent soil and nutrient losses, and insufficient soil carbon to maintain structural integrity. Above ground animal biodiversity declines.

Income potential

Small commercial livestock enterprises are unlikely to ever be profitable. This is due to scale being insufficient to adequately cover the combined fixed costs and variable or operating costs.

Those owners who learn about and implement holistic grazing methods can significantly reduce costs of production and ensure enterprise resilience in face of climate change. In such a system income can be improved by astute marketing of “boutique” meats and eggs associated with credence values consumers are looking for.

The most common financial mistake made by new landowners is chasing high productivity per hectare per 100mm of rainfall before they determine the production capacity of their pastures and its high annual variability associated with changing rainfall patterns associated with climate change. Attempts to fill feed shortages with supplementary hay, silage or grain inevitably leads to higher debt, stress for the livestock and the owners, and degradation of the farm environment.

Livestock enterprise decision chart

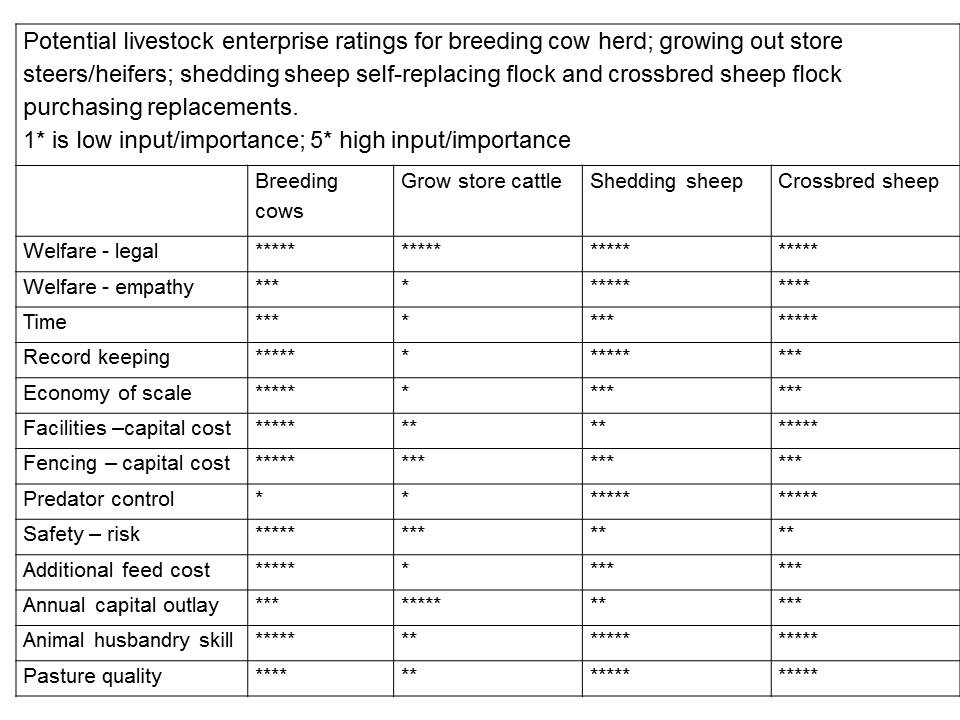

To help small landowners decide which livestock to run on their farms I have constructed a star ratings chart, table 1.

Table 1: Livestock enterprise ratings. Source: Patrick Francis.

The assumptions behind the four livestock enterprises being considered are based around a 40 ha farm with 30ha of pasture that can carry in an average rainfall year round:

- 15 breeding cows – self replacing herd, buy bull every 4th year (14 calves weaned each year)

- 35 store steers/heifers – buy & sell each calendar year (grow from 300kg to 500kg)

- 45 shedding ewes – self replacing flock, buy ram every 4th year (65 lambs weaned each year)

- 45 crossbred ewes – buy ewes every 3rd year, buy ram every 4th year (65 lambs weaned each year)

My conclusions are:

If time is short and livestock and pasture husbandry skills are low, dry cattle bought and sold each year is the simplest enterprise. The major advantage of the dry cattle enterprise is its simplicity for increasing or decreasing numbers as pasture availability increases and decreases with seasons and rainfall. The farm is easily destocked as feed levels decline and only restocked after sufficient rain has rebuilt the pasture bank. This means there is no stress on the paddock ecosystem, animal welfare is maintained and costly supplementary feed is not necessary to make or buy. Marketing is relatively simple as all stock can be easily sold at local livestock sales and possibly privately to processors or other farmers.

On the negative side there is little to animal empathy involved with store cattle. It may also be difficult to purchase sufficiently quiet stock that suit the small farm infrastructure.

For owners wanting a breeding enterprise, a shedding sheep flock is the standout. These animals are managed like small cattle as they don’t need shearing or crutching but are much safer to handle and build empathy with. Farm infrastructure requirements are low. But with sheep, ewes often conceive multiple young – twins are common and sometimes triplets, time and dedication is necessary during the lambing period to minimise lamb losses. All breeding enterprises, wether sheep or cattle, require good animal husbandry skills and good pasture management knowledge.

When comparing breeding meat sheep to breeding cattle, an important difference to note is that lamb progeny should be sold before about 12 months of age which is when their two permanent incisor teeth emerge. Two tooth sheep are not allowed to be traded as “lamb” and incur a significant market discount to “lamb”. Such a discount does not happen with young cattle. This means cattle owners do not have as critical time component to marketing young stock as meat sheep owners. It also means meat sheep owners need additional livestock nutritional management skills to ensure lambs reach market weights before they become “two tooth” animals.

Finally, small and absentee landholders would do well forming a loosely organized self-help group or club to support each other particularly if farming the same type of livestock. By working together and sharing some equipment like scales and electronic tag readers management is facilitated and costs reduced. Club members may also find greater livestock marketing opportunities if numbers ready for sale can be combined.

Appendix 1:

Advice for new sheep, goat and cattle owners from Meat & Livestock Australia’s subsidiary the Integrity Systems Company

From the moment they buy an animal, every livestock producer has a responsibility to ensure the food they produce is safe, traceable and meets customer expectations. As a producer of food, you must know all requirements. Even if you own just one cow, sheep or goat, it’s your responsibility to deliver safe product into the food chain.

Following all requirements of Australia’s red meat integrity system means you can stand by what you sell.

New producers need to:

- Obtain a property identification code (PIC)

- Learn how to ensure the red meat from your animals is safe to eat

- Become an accredited LPA producer

- Register for an NLIS account

- Buy NLIS devices

- Apply NLIS devices to your livestock

- When you are ready to move or sell your animals, order LPA NVDs

- Record movements of your livestock on the NLIS database

- Check residue history on purchased property – contact your state Department of Agriculture

- Only introduce livestock from LPA accredited PICs

- Ensure an LPA NVD is used for all livestock movements on and off your PIC(s)

for more information visit https://www.mla.com.au/meat-safety-and-traceability/red-meat-integrity-system/new-producers/

Thank you for this suitable article about livestock farming tips for beginners, it will help me and people like me looking for the same. I appreciate your effort for taking time to do your research and present these details before us. Really nice way to present this content, very appreciative!! I found this Dukeswiremesh.com Having loads of data, if possible do have a look.

Great Article

Thanks Tom