ESCAS fails stunning for sheep

Review is misleading on animal welfare

By Patrick Francis

It is baffling to me how Australia’s most credible animal welfare organisation, RSPCA, can be constantly ignored by governments, farmers representative organisations and many farmers about revealing shortcomings in the Export Supply Chain Assurance System (ESCAS), especially live sheep exports.

The fact that according to the RSPCA 88% of sheep exported from Australia are slaughtered without stunning should be enough evidence to call a halt to this trade, as without stunning animals die a cruel death. Slaughter without stunning is not permitted in most Australian states (it may still happen in limited number of small abattoirs practicing religious slaughter but details are unknown) and farmers should demand it not be allowed to happen to the animals they sell. ESCAS accepts slaughter without stunning so despite all the improvements it has put in place with respect to transport, lairage, abattoir staff training, and animal handling, it fails animal welfare.

The fact that the Australian Live Exporter’s Council (ALEC) only refers to achievement with introducing stunning in cattle abattoirs reflects ESCAS’s lack of influence in the live sheep trade.

In a 28 January 2015 Beef Central article ALEC chief executive officer Alison Penfold admittted that data on pre-slaughter stunning in foreign markets supplied with Australian livestock was not available. But for cattle the majority were stunned prior to slaughter. She said there was obviously less use of stunning when it came to sheep and goats but pre-slaughter stunning was used in Jordan.

Penfold wasn’t asked why it was “obvious” that there is less use of stunning when it came to sheep. What is obvious is that ALEC or DAFF are not taking the issue seriously, and ESCAS must have major shortcoming when it comes to sheep live exports. If ALEC was doing its job it should know exactly what the numbers of animals stunned are (its knows how many are exported), what percentage this is of the total number exported, and what is the trend for stunning adoption. Penfold said the live export industry continues to encourage the use of stunning, but if it doesn’t have any data, how would she know if the encouragement is working.

Penfold also claimed in the article that Australia cannot justify demanding its animals are stunned because non-stunned slaughter is happening in this country. That is a weak argument, more of an excuse for doing nothing about the issue. If ALEX was serious that stunning should be adopted in overseas abattoirs processing Australian livestock then it could also lobby any state governmenst here which allows non-stunned slaughter to introduce legislation to stop it.

It is also important to understand that as a quality assurance program ESCAS does not protect animals from cruelty. That’s because it treat animals just like factory QA programs treat widgets. If there is a non-conformity for widgets, they might not work or look as intended, but they don’t suffer. Live animals unlike widgets will suffer if there is a non-conformity in the way they are transported, handled and accomodated. ESCAS helps minimise the opportunity for animal cruelty in the supply chain but it will never overcome it happening especially with sheep where a commodity culture exists.

Added to its inability to protect livestock from cruelty, ESCAS also suffers from a lack of commitment from the federal agriculture department to apply penalties when non-conformities occur. If live exporters were vigorously pursued when non-conformities occur then it may have a level of legitimousy for animal welfare provided stunning is mandatory. Even one major live export company, Wellards, commented recently that if some of the maverick operators, especially in the developing markets, were fined for ESCAS non-conformities, standards in the trade would be improved.

Scot Braithwaite general manager Asia with Wellard Rural Exports told the WA Country Hour on January 6:

“I would like to see the rules enforced a little more strongly from the point of view of people who are outside or are found to be doing the wrong thing. We need to have someone slapped on the wrist just to make sure that we are still all doing the same thing. Something that at least shows that if we do go outside the rules there is a penalty for it happening.

“I know it’s very difficult to get a prosecution and it’s a very serious thing to take someone’s licence from them, but a suspension or something probably would just assist us to keep the next line of clients aware this is a serious process,” he said.

Apart from regular reports of cruelty in the live sheep trade there is no economic case for Australian sheep farmers to be involved in it. All the sheep currently exported could be processed in Australia (particularly in Western Australia where abattoirs are operating below full capacity due to the decline in the state’s sheep population) and their meat exported with equal or possibly higher returns for the farmers involved. This would make more jobs available in Australia (particularly WA) and would provide farmers with carcase feedback which could be used to increase livestock value through genetic selection for carcase and meat quality traits.

Figure 1: The WA farmers can add more value to their sheep and improve flock genetics by finishing animals on-farm for local processing rather than exporting them for unknown entities to take advantage of the value adding. By doing so they remove most of the animal cruelty that live sheep are enduring. Photo: Patrick Francis

Live feeder cattle a different industry

For live feeder cattle exports the logistics are very different as in most cases joint ventures between suppliers, overseas feedlots (especially in Indonesia) and processors are in place. Joint ventures rely for their profitability on whole of chain accountability, transparency and best practice. The numbers of farm businesses involved as suppliers is small (many are large corporate farms such as Consolidated Pastoral Company and AACo) compared to thousands of sheep suppliers, and importantly the value of each animal involved in much higher (a feeder steer at around $600 each versus a slaughter wether at around $80 each). The greater the value of an animal the more likely its welfare will be looked after more carefully.

Another important difference between the live export trades for cattle compared with sheep, is the locality of the producers involved. Unlike sheep sourced mainly from the south west agricultural corner of WA, live cattle are sourced from farms across the Top End. The farms rely on cattle for their business survival and have no alternative outlet (AACo has just opened the Top Ends first export abattoir near Darwin mainly for its own cattle) as it is difficult to finish animals to specification for domestic and exports markets. The cattle breed, Brahman (Bos indicus) and its crosses are adapted to hot climates, and transport time to Indonesia is only a few days.

It is also important to realise that the exported cattle are mostly destined for finishing in feedlots in Indonesia which use local products as cattle feed. This is a key issue to understand as these sources of carbohydrate would be wasted (go into landfill) if not for the ruminant animal’s ability to convert herbage into meat protein. The feedlots therefore add value to the young cattle which cannot be finished on their Top End farms and provide local employment. (The fact that the WA and SA feedlot sectors are small indicates that the economics of transporting young Brahman cattle from the Top End and finishing them on grain based diets in the states’ agricultural zones, doesn’t stack up.)

But live cattle exports are developing a new trend (especially to Vietnam) where slaughter animals are shipped for processing overseas. This development is less likely to involve joint ventures and chain transparency which leads to the “commodity culture” characteristics of live sheep exports and opens the door wider to potential animal cruelty. The farmers involved loose contact with their animals, they don’t receive feedback for genetic selection, and Australian meat processors loose opportunities to employ more workers in abattoirs and boning rooms.

An interesting scenario for the trend of processing more finished Australian cattle in overseas countries like Vietnam will be to follow the beef value chain post the abattoir. It will not be surprising if beef marketed as “Product of Australia” that is processed in Vietnam being sold (via grey channels) in emerging markets like China or even into established markets such as Japan and competing with beef brands from cattle processed in Australia. Knowing that Australia’s meat processing costs are significantly higher than those of south east Asian countries live cattle export for slaughter (as opposed to finishing overseas then slaughter) may follow Merino wool and become another of Australia’s bulk export commodities, paid for accordingly, and processed and value-added by overseas companies.

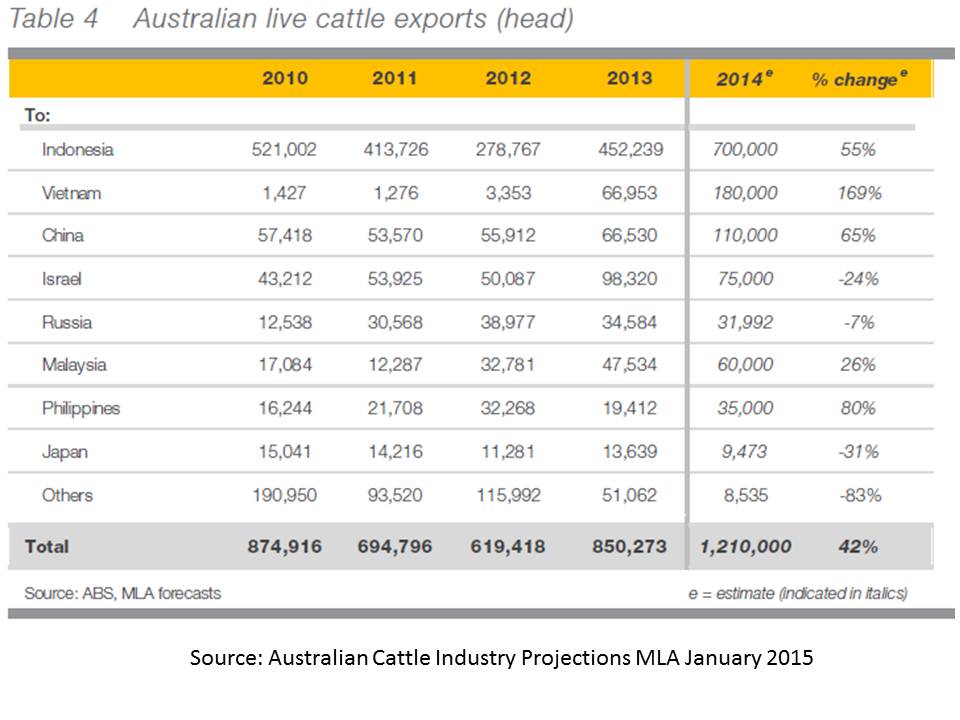

A sense of what is happening with Australian beef in Vietnam can be gleaned from MLA’s January 2015 Beef Industry Projections. In the review of “Other Asia” beef export opportunities Vietnam does not register (in its figure 48) as importing any significant amount versus increasing imports by the Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand. Yet in the “Live exports – summary” in 2014 Vietnam emerged as Australia’s second largest importer behind Indonesia, importing an estimated 180,000 cattle, Figure 2. Incredibly in 2012 Vietnam was our smallest live export market importing just 3353 cattle. Given Vietnamese are not large beef eaters (according to an MLA graph about 8 kg per capita per year) it is not unreasonable to speculate what dinner plates the beef from the imported Australian animals will end up on.

Figure 3: Australian live cattle exports by destination 2010 to 2014. Source: MLA

An ABC Rural report by Matt Brann in December 2014 demonstrates what may be happening in Vietnam with finished live animals imported from Australia. One company Animex has imported around 75,000 head Brahman type cattle from northern Australia. It is delivering Australian beef into a handful of supermarkets around Hai Phong and Hanoi, and the sales have been excellent.

Customers are told the beef is not imported frozen, but has come from live Australian cattle which have been slaughtered at a nearby facility and sent straight to the supermarket fresh.

“Beef is clean fresh meat, which preserves the meat standards, so very sweet, sweet taste characteristics of Australian beef, easy to prepare healthy and safe. (It’s) unlike most Australian beef on the market [which] is frozen beef imported from Australia and thawing improperly will lose sweetness,.” says the online advertisement.

This chilled Australian steak is currently being sold for around $AUS16/kg and beef tenderloin is selling for over $AUS17/kg. These are up-market supermarket beef prices, not low value wet market prices (Incidentally MLA says that in 2014 the average retail beef price in Australia was $15.94). An in-shop advertisement hording promoting the Australian beef shows British breed cattle, not Brahmans, Figure 3.

Figure 3: Will Australian finished live export cattle compete for market share overseas with our own chilled and frozen beef. Photo: ABC Rural Matt Brann 21 December 2014.

What the RSPCA said about the ESCAS report

Source: RSPCA Australia media release , 21st January 2015

The Government’s review of the Export Supply Chain Assurance System provides false assurance to Australian cattle and sheep producers about the welfare of animals exported live from Australia.

The Export Supply Chain Assurance System (ESCAS) was put in place by the Australian Government following exposure by ABC’s Four Corners in May 2011 of the horrific treatment of Australian cattle in Indonesia.

Heather Neil CEO RSPCA Australia said ESCAS has set a low bar and fails to prevent major suffering for Australian exported animals.

“The report has glossed over the fact that ESCAS does not require animals to be stunned at the point of slaughter, nor requires animals to be held upright for slaughter, meaning they will be fully conscious of the pain and suffering associated with the cut of the throat,” said Ms Neil.

“Allowing unstunned slaughter is much more than just a ‘potentially adverse animal welfare outcome’ – it is horrific cruelty.

“No respectable animal industry in Australia would dare suggest that only 0.16% of animals experience adverse animal welfare outcomes in their production systems – it shows how desperate the Government is to spin the numbers and hide the real facts from Australian producers about the treatment of their animals overseas.”

“Eighty eight percent of sheep exported last year or 1,709,583 were slaughtered while fully conscious, it is only sheep that go to Jordan that are usually stunned – and this goes above and beyond ESCAS. To add to this, since 2012, 187,877 cattle were not only slaughtered while fully conscious but were also turned upside down before slaughter,” Neil said.

Lost in the middle of the report is a sentence that acknowledges the Government does not know how well the reported non-compliances reflect the true non-compliance rate.

“It is important to know that our Government does not inspect or even investigate complaints of ESCAS breaches on the ground in importing countries – that has been left largely to animal advocacy groups. Any claim that there is widespread or ongoing compliance with all of the requirements of ESCAS has no sound basis in fact,” said Ms Neil.

“Despite clear evidence of Australian cattle being tortured in Gaza, scenes of cruelty as bad as we saw in Indonesia in 2011, as well as sheep dragged and being killed in back streets in other countries, the report acknowledges that no exporter has been prosecuted due to failure to meet ESCAS requirements.

“The report makes no recommendations as to how the enforcement of the system can be strengthened.”

The RSPCA has significant concerns about the ability of the live export industry to deliver the animal welfare outcomes that are expected by the Australian community, with the report flagging the development of an industry quality assurance scheme.

“The live export industries are proven failures in self-regulation – it is why ESCAS was introduced in the first place.

“Rather than continuing to provide false assurance about the welfare of Australian animals overseas, the Government and cattle and sheep industries need to move away from high risk live exports and continue to expand the much more valuable red meat export market, worth almost $9 billion,” said Ms Neil.