23 years on “father” of landcare’s fundamental message is worth re-reading

By Patrick Francis

In 1990 I wrote an article for FARM Magazine after interviewing the farmer behind Australia’s first landcare group. Terry Simpson raised some important issues about the future for landcare farming some of which have gone missing in the movement’s policy and implementation levels.

At the policy level the basis on which landcare was engaged and implemented by farmers in 1990 was in stark contrast to how it is today. Simpson changed management and practices to improve soil health and pasture climate resilience – not that he used those terms, and subsequently lifted productivity on degraded paddocks. In carbon terms, he boosted carbon flows above and below the soil by growing more productive pasture species which responded to fertilisers. More soil cover and higher soil organic matter meant rainfall was absorbed rather than ran off which in turn boosted pasture growth and provided more carbon for the soil food web. This in-turn meant he was able to increase stocking rate and had more income to spend on improving soil health and pasture resilience on other paddocks across the farm.

With today’s level of knowledge about connections between native pastures, plant nutrition, nutrient balances, spring-summer pasture spelling, rotational grazing, the soil food web, biodiversity and animal welfare, then I am sure Simpson’s strategy would be far more holistic, despite this the fundamentals for improvement were still there.

There are a few aspects associated with Simpson’s 1990 approach to landcare which have gone missing over the subsequent two decades.

Firstly, Simpson undertook a program which was monitored and assessed for outcomes – both environmental and financial. Learning from those outcomes Simpson knew he could afford to repeat the strategies in other paddocks and did so using his own capital. Today the knowledge needed for farmers to implement landcare farming strategies eg boost soil health, boost ground cover, increase rainfall infiltration, boost soil carbon percentage, increase biodiversity etc is known for virtually every region. But many farmers won’t act unless funded to do so. Hundreds of millions of dollars are spent annually in landcare programs to ensure adoption.

The rational for this policy approach is that for many farmers enterprise profitability is so low or non-existent that without funding, the necessary management changes and possibly capital investment would not be implemented. Yet there are farmers who have sort out new knowledge and adapted management strategies and if necessary (often in grazing businesses it is not) invested their own capital in machinery and/or infrastructure which is improving soil health, biodiversity and climate resilience, and subsequently their enterprise profitability. These farm businesses are not acknowledged or financially rewarded for the environmental outcomes achieved. The question here that needs more debate is should farmers landcare outcomes or stewardship be rewarded as an alternative to financing bureaucrat determined programs in the hope of achieving political outcomes.

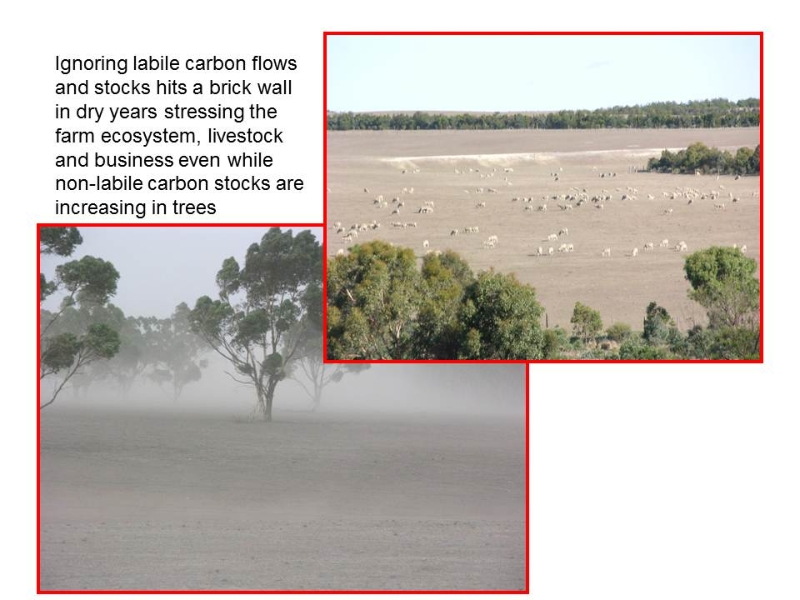

The second issue which stands out from Simpson’s remarks which has failed to be addressed through landcare over the last two decades is the importance of programs taking a holistic approach to environmental management. Despite the plethora of research projects associated with climate change and importance of resilience, many farm environments are devastated every time there is a dry spell/drought and at the breaking of the drought.

When Simpson said: “These trees attract people’s attention, they look good, they look like landcare, but what many fail to appreciate is that the real landcare surrounds the trees,” he hit the nail on the head about the silo thinking associated with so many landcare programs.

At the other extreme high input, productivity based programs like Beefcheque, Prograze, Lifetime Ewe Management, concentrate farmers thinking around boosting pasture growth and livestock productivity, ensuring livestock consume up to 80% of what is grown, and neglect protecting the soil, enhancing the soil food web and above ground biodiversity, and maintaining carbon stores and flows above and below ground over the 12 month seasonal cycle.

Evidence of this failure is clearly seen across southern Australia in spring, summer and autumn especially when rainfall over this period is below average. Even on landcare program participating farms criss-crossed with excellent tree and shrub corridors, the bulk of the farm land is often degrading – losing pasture plants, top soil, nutrients and carbon to wind and water erosion, figure 1.

There is another interesting comment in this article, Simpson’s use of cover cropping the phalaris sub clover pasture with oats. This is a form of pasture cropping which has become a more common practice especially in summer active native pastures in eastern Australia and summer active sub-tropical perennials in the WA wheat belt.

Simpson didn’t have the technologically sophisticated no-till drills common today but he was still able to over-sow oats into a pasture to boost autumn and winter feed supply. Pasture cropping is often used for this livestock feed production purpose as well as winter grain cash crops. It’s great advantage on native pastures and sub-tropical perennials is that the cereal crop is actively growing when the pasture is dormant. The cereal can be fed or harvested without damaging the pasture below and the pasture is ready to grow on during summer and autumn.

Many Catchment Management Authority and landcare group projects have been funded to trial pasture cropping after it gained increased prominence during the early 2000’s. Instead of farmers taking the initiative themselves to try the concept most waited until landcare funds were made available to them before doing so.

Programs that rely on landcare funding before farmers take action can have some unintended consequences in some areas of farm environmental management. The most notable are associated with weed and pest control. Instead of acting at the most critical and effective time, some farmers wait until grants are provided to take action. This can often lead to the pest plant or animals becoming a greater problem or action been taken outside of the most effective time.

This is an edited version of the original article from FARM Magazine June 1990:

Landcare can be practised on a far larger scale than it is at present if productive programs are developed for farmers. Around the Winjallock district near St Arnaud Vic, 95 percent of farmers are involved in a landcare program.

This high participation rate is largely due to local grazier Terry Simpson,who has been able to demonstrate, with the help of Conservation Forests and Lands and the Department of Agriculture officers, to neighbors that the program boosts productivity as well as saving soil.

Simpson with his son Greg runs 10,500 Merino sheep on 2600 hectares of the Avon and Richardson rivers catchment area. Treeless, rocky ranges cross most of the properties and are the main challenge as far as landcare is concerned. Run-off from the ranges causes sheet erosion on the slopes and gully erosion on the plains below.

For 20 years Simpson has countered erosion on his property with phalaris, sub clover and superphosphate. His success has not gone unnoticed; and the first Victorian Landcare group was launched on his property four years ago. Through his involvement with the Victorian Farmers Federation Simpson is a major spokesperson for practical landcare.

Simpson’s own landcare program is based on productivity. By sowing down the highly erodible hills to the deep rooted phalaris and sub clover he is immediately able to boost carrying capacity on the country. This in turn leads to increased farm profitability which helps pay for the program and ensures its development.

This broad-brush approach, which is relatively low cost at $64 a ha ($35 a ha for dozer hire $17 a ha fertiliser $12 a ha seed) means a large area can be treated in one 1year with an almost immediate impact. Hillside trials (table 1) Show run off from phalaris/sub clover sown areas making up 1.1 percent of total rainfall while on untreated land, runoff comprises up to 36 pc of rainfall.

The reasons for the difference are:

- the phalaris sowing involves cultivation which leaves the soil surface rough;

- Pasture cover on the phalaris plots is much better; and

- the soils under the phalaris plots are generally drier despite the higher amounts of infiltration.

The major benefits from the reduced run-off are:

- greatly increased production as more moisture is available for plant growth.

- reduced soil erosion problems downstream; and

- reduced frequency of run-off events.

At the same time as sowing a section of range, Simpson cultivates arable land below it and sows a cover crop (over phalaris and sub clover) of Echidna oats at 15 kilograms a ha which is around one third of the normal rate. Echidna is chosen because of its low height. This combined with the low rate, mean competition for the pasture for light is minimised.

Paddock improvement

Once the cause of the soil erosion has been checked and a paddock’s stocking rate lifted from one sheep to two ha to three sheep a ha Simpson works on improving other paddocks by improving water supply, diversion banks, rabbit control, fencing, filling in gullies and tree planting

In a 146 ha paddock a new dam costs $3000. At the pre-improvement stocking rate that works out at $50 a head, but after improvement it costs only $6 a head Similarly with rabbit control, if a paddock is only returning $2000 year it is difficult to spend $1000 on rabbits. But if it’s returning $20,000 that S1000 on rabbits doesn’t look too bad, “Simpson says.

It is this practical but business like approach to landcare that set Simpson apart and sometimes at odds with some Department advisers In particular he thinks too much emphasis is put on trees to solve soil erosion problems.

“Trees give some farmers an inner glow, just like a sherry. They can see something for their work. Unfortunately in our area trees won’t solve our erosion problem and most farmers won’t become involved in programs associated with them. Because they are so expensive and labor intensive to plant and protect, most farmers can’t afford to implement broadacre programs with trees.

“On top of this there is no production benefit from increased carrying capacity with tree planting.”

Pointing to a 30 ha paddock near his front gate that is part of a block purchased a few years ago, Simpson says many landcare visitors comment on the patch of fenced trees around what was once an eroding gully.

These trees attract people’s attention, they look good, they look like landcare, but what many fail to appreciate is that the real landcare surrounds the trees. It’s the phalaris and sub clover pasture that reduces runoff off into the gully and enabled me to generate funds to dig a dam at the top of the gully and divert overflow from it, then fill in the gully.

“It’s the pasture that is the real feature of landcare in the paddock not the trees. They are only cosmetic,” says Simpson.

Table 1: How pasture affects runoff on Stricta Hill

|

1985 Rainfall 478mm |

|||||

| Plot No. | Phalaris Plots mm Runoff | % Total Rainfall | Native Plot No. | Pasture Plots mm Runoff | % Total Rainfall |

| 1 | 6.4 | 1.3 | 5 | 202.4 | 42.3 |

| 2 | 7.9 | 1.7 | 6 | 52.8 | 11.0 |

| 3 | 1.9 | 0.4 | 7 | 75.5 | 15.8 |

| 4 | 4.5 | 1.0 | 8 | 127.7 | 26.7 |

| Average | 1.1% | Average | 24.0% | ||

|

|

|||||

|

1986 Rainfall 447.8mm |

|||||

| 1 | 18.1 | 4.0 | 5 | 225.8 | 50.4 |

| 2 | 14.9 | 3.3 | 6 | 23.2 | 5.2 |

| 3 | 3.0 | 0.7 | 7 | 170.0 | 38 |

| 4 | 2.5 | 0.6 | 8 | 222.2 | 49.6 |

| Average | 2.1% | Average | 35.8% | ||