Lambs, pastures, wildlife a 2023 spring bonanza

By Patrick Francis

A combination of pasture and grazing management strategies combined with good seasonal conditions over the 2022/23 summer and autumn have resulted in our best ever lambs born percentage of 173%

Summer pasture growth benefited from the exceptionally wet 2022 spring because our multi-species perennial pastures include summer active varieties of cocksfoot and tall fescue. These provided high quality nutrition for ewes prior to and during joining starting 20 March, ensuring all condition scores were above 3.5.

Post the five week joining period, our entire breeding flock rotationally grazed paddocks at around 80 to 100 dry sheep equivalents per hectare. This period from mid-April to early August is the time dry ewes can be run at a higher stocking rate for optimum autumn/winter pasture utilisation.

Weather conditions during lambing from 20 August to 20 September were normal with maximum temperatures in the 8 to 10 degree range. Some days with strong northerly or south westerly winds resulted in wind chill temperatures below 0 degrees. We had no lamb deaths due to weather exposure, but lost two lambs to foxes.

Ewes lambed in smaller groups this year in paddocks starting with a minimum 3000kg per hectare green dry matter, figure 1.

Figure 1 : Pregnant ewes in their lambing paddock with 3000 kg green dry matter per hectare three days before the due lambing commencement date. Photo: Patrick Francis 18 August 2023.

Pasture height was above 20cm so lambs always had protection from wind chill, figure 2. Our objective was to keep ewes and lambs in their paddocks with sufficient high quality pasture to last six weeks. This allows more accurate observation as we know exactly when each ewe lambs and how many lambs she has. It enabled us to quickly identify that two lambs were missing and conclude fox predation. This set stocking system also helps identify mastitis cases because an affected ewe’s lambs usually stand out as not being fed. 95% of lambs were born in the first 18 days of lambing giving us the idea that joining can be reduced to four weeks rather than five weeks.

Figure 2: Pasture quantity above 2000 kg green dry matter per hectare in lambing paddocks not only provides ewes with optimum nutrition, it also helps avoid worm larvae intake and provides lambs with protection against wind chill. Photo: 13 September 2023 Patrick Francis.

Lamb marking was done at five to six weeks of age. We continue to use analgesic for castration with an injection into the testes. Its impact on lamb comfort is obvious straight away, they show very little discomfort behaviour but do lie down more than ewe lambs. We do not remove tails as our sheep are selected for shedding ability and fly strike isn’t an issue for them. We let lambs rest for around an hour before re-joining them with their mothers. There is no issue with matching up lambs to ewes in approximately 10 minutes after mixing – another sign that the castration analgesic has done its job. Using temporary neck tags on lambs we have a system to match each ewe with each lamb and it National Livestock Identification System (NLIS) ear tag number.

Average lamb weight at marking was 16 kg and average growth rate 309 grams per day (range 270 – 340 for different flocks on different pastures). Lamb age at marking was 5 to 7 weeks.

Lamb weaning was on 25 November which meant 90% of lambs were between 11 and 14 weeks old . Average growth rate from birth to weaning was 264 grams per day. Lambs are vaccinated with 6 in 1 and drenched. They are moved onto high quality finishing pasture, which has been rested from grazing since June, so would have very low worm larvae contamination, if any.

Methane reduction with quality pastures

Lambs were weaned directly into saved chicory, clovers and ryegrass pasture with around 5000kg green dry matter per hectare. These special purpose weaned lamb pastures are part of our strategy to minimise methane production per kg of carcase weight. Our average lamb birth to weaning growth rate per day per ewe increased by 20 grams to 448 grams per day compared to 2022 (see 2022 Spring update).

With all the flock recorded on Sheep Genetics Lambplan, selection of breeding ewes is based on the Maternal Carcase Production index which takes account of each individual’s growth rate and fertility while we also assess for 100% wool shedding and structural soundness. The combination of high digestibility, high quality pasture with Lambplan MCP index selection gives us the best opportunity to minimise flock methane emissions on a continual basis while increasing productivity per hectare.

Moffitts Farm has the only Wiltipoll flock in Australia currently using Lambplan.

Figure 3: After drenching and 6 in 1 vaccination weaned lambs are moved onto high digestibility chicory, perennial clovers (white and red) and ryegrass pasture to optimise growth rate and minimise methane emissions per kg carcase weight. Photo: Patrick Francis 25 November 2023.

Pasture renovation

Our pasture renovation program continued through 2023 but this time with a different emphasis on ratios of species used. In the past we have placed most emphasis on perennial grass establishment with multiple species of the perennials cocksfoots (summer active and summer dormant varieties), tall fescues (summer active and summer dormant varieties), phalaris, brome grass and ryegrass. Sub clovers and white clovers are added but at around 15 – 20% of the mix. These mixes have been successful but our experience is that over time the grasses become more dominant and the legume component declines. While these pastures are highly resilient to climate change and maintain 100% ground cover during drought (helped by our grazing management program), the demise of legumes reduces soil nitrogen fixation which must have an impact on grass species growth, palatability and digestibility.

So our new emphasis is on sowing pastures with multi-species but a higher percentage of them are perennial clovers – whites, reds and sub clovers to achieve around 50% legume in the mix. Advantages of increased perennial clover percentage in our environment with around 30% of annual rainfall happening through summer are :

* Nitrogen fixation to provide nitrogen for perennial grasses without the need for nitrogen fertiliser in winter or early spring when soil microorganisms are relatively inactive due to low soil temperature.

* Highly palatable and digestible food which minimise rumen methane production per kg of carcase weight.

* Summer green pasture as perennial clovers continue to grow providing soil moisture is adequate and grazing management provides sufficient rest. (They also contribute to fire protection if strategically planted)

When the herb chicory is included in the mix summer green pasture is boosted even further. However, unlike perennial clovers and sub clovers, chicory is not winter active and has little feed value during that season. It makes up for this deficiency by being more dry season resilient with its tap root accessing moisture deep in the soil profile.

The summer growth advantages of perennial clovers in our environment are not applicable for agricultural areas further inland which have a Mediterranean rainfall pattern, where summer rain is absent and summer active grasses and legumes (exception lucerne) quickly die out. Those areas are suited to sub clovers as the principle legume as they are annuals, dying out in late spring and regrowing the following autumn break.

The other refinement to the mix is being more selective of the perennial grasses used in different paddocks. Our experience with both summer and winter active cocksfoots is that they don’t like soils that experience longer periods of water logging and the three most unwanted “weed” grasses that are endemic on wetter soils in southern Victoria, bent grass, sweet vernal grass and Yorkshire fog grass can take its place and become dominant. So we are being more particular about where cocksfoot is sown, giving it slopes and better drained soil types. Tall fescues and phalaris are more suited to the wetter soils.

The three “weed” grasses prevalent in the district (and much of southern Victoria) have two other characteristics which make their control even under holistic grazing difficult.

Firstly, they are unpalatable especially to sheep so are difficult to suppress with high stocking rate grazing management unless you have dry wethers for the purpose. Using this technique with lactating ewes or lambs would be highly stressful for these stock due to the grasses low palatability and would lead to significant reduction in milk production, ewe condition and lamb growth rates.

Secondly, they have significantly different flowering times, sweet vernal starts flowering early September, Yorkshire fog from late September onwards and Bent grass from late November to end of December. The flowering stems are completely unpalatable to sheep and a paddock becomes a patchwork of grazed (possibly overgrazed desirable species if not managed carefully) and ungrazed areas.

A temporary solution which helps the unpalatable grasses patchwork from developing is pasture topping with a slasher, but because of the different flowering times, this is usually needed at least twice up until Christmas. Persistent slashing does help prevent more seed set of these unwanted species and when desirable grasses and legumes are present favours them under rotational grazing management.

Figure 4 : The trio of unpalatable low productivity perennial grass weeds can overrun and out-compete desirable pastures in spring due their early flowering and reluctance of lactating ewes and lambs to eat their leaves. Photo: Yorkshire Fog grass flowering and without intervention will squeeze out the white clovers nearby, November 2023.

We will not convert the entire farm’s pastures to the 50% legumes, chicory and ryegrass mix as there is an important role for multi-species perennial grass dominant pasture to provide climate resilient bulk dry matter for dry stock. In a prime lamb enterprise, ewes can be grazed like dry stock, such as wethers, for about 55% of the year:

* post weaning until two weeks pre-joining, about 12 weeks over summer

* post joining until four week pre-lambing, about 18 weeks over autumn and winter.

The majority of these weeks are in seasons when pasture availability can be an issue and is a time many farmers supplement ewes with grains or hay/silage. We do not want to supplement ewes preferring to grow as much pasture as they need year round for optimum condition score. So, high dry matter producing pastures, based on multi-species perennials, become the living hay stacks for the two periods above. These pastures can be managed to accommodate high stocking rates, 80 to 100 dry sheep equivalents per hectare for moderate lengths of time under rotation and even in winter will regrow depending on the length of grazing rest.

While the digestibility and quality of these multi-species perennial grass pastures may not be optimum for livestock, for their purpose of maintaining condition score of dry ewes as well as providing a climate resilient feed source without additional supplementation, they are an important contributor to the farm’s ecosystem services.

The one drawback with these prolific grass pastures is they usually need a slashing intervention in autumn as a way of returning flower stems to the soil and to stimulate more tillering for winter growth. While we don’t want more diesel emissions from slashing the bulk of feed grown means there are no diesel emissions from making or buying-in supplementary feed or from distributing supplementary feed to animals. The ecosystem services including CO2 abatement and climate resilience, provided by these bulky perennial pastures more than compensates for the slashing emissions.

Figure 5A : Our multi-species perennial grass pasture with summer active varieties can be difficult to keep vegetative during wet summers. While they look dry due to flower stems, they contain a considerable amount of green leaf. Topping with a slasher returns stem to the soil surface for quicker breakdown into soil organic matter and stimulates plant tillering providing a significant pasture availability boost leading into winter. Photo: Topping 5 April 2023, Patrick Francis.

Figure 5B: Pastures are topped at approximately 12 -14cm high exposing green leaves and giving sheep easier access to them. Photo: Same pasture as above on 5 April 2023, Patrick Francis.

Pasture sowing strategy

We took a different approach to pasture renovation logistics this year. Given our near record production of dry matter over summer due to excellent 2022 rainfall, two paddocks were set aside for renovation using knock down herbicide twice over winter to remove as much bent grass, sweet vernal and Yorkshire fog as possible. These three grasses can “escape” control in a traditional late spring to autumn knockdown spray. By spraying twice between the autumn break and late winter all unwanted plants were removed.

Evidence for this was seen in a small patch which I considered didn’t need a second spray in winter as so few plants had regrown after the first late autumn spray. I was wrong. After direct drill sowing the pasture in late September, the unsprayed patch is contaminated with the three unwanted grass species plus thistles, all competing successfully with the sown pasture varieties and decreasing their competitiveness.

Figure 6A. This small section missed the August knockdown spray with significant consequences. By November, bent grass and sweet vernal grass plus thistles are so competitive the chicory and clovers have not germinated and survived like in the rest of the paddock. Photo: 30 November 2023 Patrick Francis

Figure 6B: The rest of the paddock shown in Figure 6A. Here germination of chicory, clovers, phalaris is even and unimpeded by weed species despite a three week dry spell and hot days post sowing. Photo: 30 November 2023 Patrick Francis

Figure 7: A three year old pasture direct drill sown with perennial clovers, perennial ryegrass and chicory. This photo taken on 7 November 2023 3.5 weeks post grazing with ewes and lambs demonstrates how quickly these pasture respond to rest, growing from 1500kg DM/ha to 3000kg DM/ha. Note the chicory has disappeared from the pasture which in our experience is normal. Providing the pasture is fertilised the perennial clovers, sub clovers and perennial ryegrass should maintain productivity if unwanted perennials can be kept in check. Photo: Patrick Francis.

Figure 8: This pasture was direct drill sown with chicory, perennial clovers and sub clovers and a low rate (1kg per ha) of perennial ryegrass in 2021. The thinking behind the low perennial ryegrass rate was to prevent it becoming too dominant as in Figure 7 paddock and encouraging persistence of chicory. This strategy is working so far with the paddock retaining a considerable amount of chicory amongst the perennial clovers. Another potential advantage of this low ryegrass seed rate is the ability to easily direct drill oversow with more chicory and clovers in Autumn without requiring a knockdown herbicide. Photo taken 21 November 2023 after two weeks rest from grazing by ewes and lambs.

Figure 9: Spreading 4 tonne per hectare chicken litter on the same paddock as Figure 8 in early June 2023. Chicken litter is an outstanding low carbon emissions long acting fertiliser providing plants with a suite of nutrients as well as labile soil carbon for mineralisation (plant nutrient availability) over a two year period. Photo: Patrick Francis 7 June 2023.

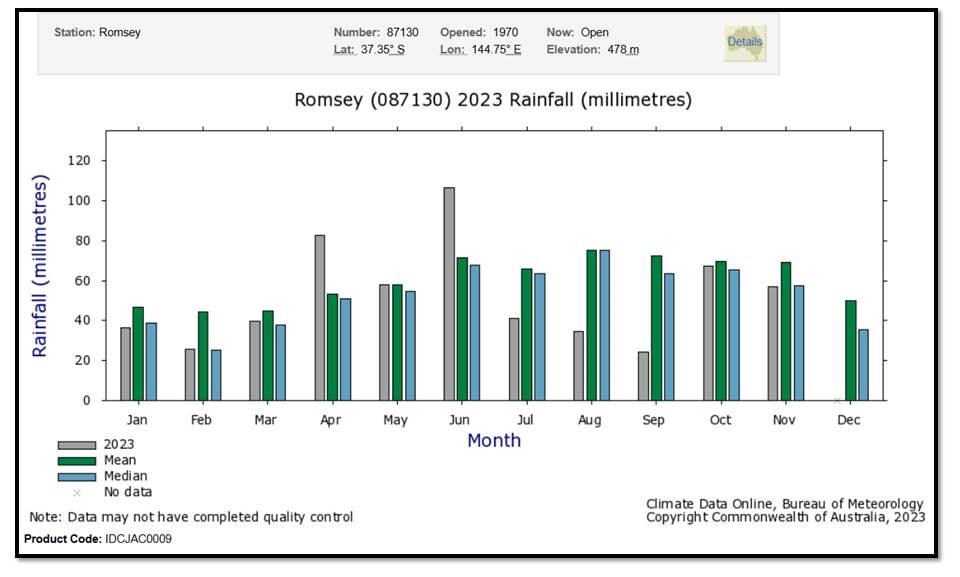

Figure : Rainfall averages can be deceptive. In 2023 we were heading for a failed spring but one local storm event on 4 – 6 October delivered 57mm which set up pastures especially the newly sown chicory/perennial clovers for outstanding growth into summer. Without that storm total October rain would have been around 10mm ensuring spring was one of the driest on record. Further storms in low pressure systems in late November and late December turned the season on its head from a BOM predicted below average rainfall spring (under influence of El Nino) into a bonanza for summer pasture growth given we sow summer active varieties of herbs, clovers and perennial grasses. Source: BOM

Pasture sowing steps

Under our grazing management system where multi-species perennial grass weeds can become dominant after 10 to 15 years there are specific steps needed for renovation. The situation is complicated by our instance on maintaining 1200 – 1500kg dry matter per hectare across 100% of the soil surface year round. The additional bulk of material adds a cool burning step compared to standard practice where multi-species perennials are not present or they are grazed over summer/autumn to less than 600kg dry matter per hectare.

Step 1: Knock down spray after two conditions are met: A: the autumn break has stimulated good unwanted species regrowth and germinated annuals like silver grass and cape weed. B: the total dry matter is less than 1500kg dry matter per ha achieved by grazing or slashing. Photo: 15 April 2023.

Step 2: Cool burn post autumn break. This is particular to our grazing management where we always retain 1200 – 1500kg dry matter per hectare across the paddock. After the knockdown spray has taken effect this level of dry matter prevents sowing with our Baker boot direct drill so burning is needed. Photo 24 May 2023 Patrick Francis.

Step 3: Second knockdown spray. The paddock is left fallow over winter. Second knockdown spray in August with the aim of a September sowing, crossing fingers that early spring rainfall provides a window to sow. Photo: Second knockdown spray using a Mad Rabbit line marker to guide spraying. Note the amount of post first spray plant germination and regrowth of some persistent perennial grasses. Without the second spray this regrowth would out-compete newly sown seeds in spring leading to a renovation failure, see Figure 6A.

Step 4: Direct drill sow. The second knockdown spray has worked well leaving a clean weed free soil surface suitable for direct drilling using Baker Boots (points). Spring rain is the biggest threat to this approach as in our district spring rains can delay sowing to late November which is less than desirable and if summer rain is below average a potential sowing failure. Sowing in autumn is safer than in spring due to longer sowing windows with drier soil, but weed removal is less certain as many annuals and perennials can germinate post sowing in winter. Potential for water logged soil and cold over winter months can put newly sown species at a competitive disadvantage. Photo: Sowing 16 September 2023.

Figure: Three months later. With late spring and summer storm rain the September sown chicory, perennial clovers pastures responded accordingly providing high quality. lower methane emissions feed for weaned lambs. Note the double MLA ruler is 28cm high. Compare this image to Figure 6B. Photo: Patrick Francis 14 December 2023.

Biodiversity update

2023 spring has been unusual for honey bee activity. We have had three swarms around the cottage garden, the first time ever. What triggered these is unknown but it may have been associated with prolific flowering in our planted southern blue gums (E. globulus). These trees which form the majority of our agroforestry planting since 1990 produce magnificent flowers and have also attracted thousands of Plague Solider beetles, Chauliognathus lugubris. They are a native beetle and do not damage the flowers they feed on.

Figure: Bee swarm around hollow in base of tree September 2023. Two more swarms were collected by an apiarist in October. Photo: Patrick Francis.

Figure: These Plague Solider beetles were attracted in their thousands to flowering southern blue gums. They congregate below the gums on surface high spots like rocks and blades of grass during the cool of early morning Photo: Patrick Francis November 2023

Figure : The flowering southern blue gums have created enormous interest amongst insects. Plague Solider beetles were feeding on the pollen and nectar. Photo: Patrick Francis November 2023.

Another exciting sighting in the blue gum forest was a family of sugar gliders. Given the plantation is less than 30 years old, the sugar gliders return to the farm shows how important revegetation in large forestry blocks can be for biodiversity and carbon abatement.

Reptiles have been active since mid-September with a number of sightings of copperhead snakes and blue tongue lizards. It is interesting that by summer sightings are less frequent.

Figure: Copperhead snakes and other reptiles like bluetongues and skinks are becoming more common in spring over the last 15 years as the food web expands across the farm. Photo: 14 October 2023 Patrick Francis.

As for birds the most unusual occurrence has been the large number of White Faced herons and some Pacific herons feeding in the clover, chicory, ryegrass pastures. Usually we only see these birds fedding close to dams but there could be an association between stimulus to the soil food web from the poultry litter applied to these pastures in June, figure 9.

Figure: An unusually large number of White faced herons and smaller number of White Necked (Pacific) herons have been feeding across our chicory, clovers, perennial ryegrass pastures throughout winter and spring. Photo: Julie Francis.

One completely new bird species has been identified this spring, a spotted pardalote. It is nesting in a machinery shed but we haven’t been able to find the need.

Figure: A pair of spotted pardalotes was identified on the farm for the first time this spring. Photo: Patrick Francis October 2023

Birds nesting in our sheds is common and highlights the associations that can be made between native animals and the built environment. Grey Shrike Thrush and scrub wrens are the most common “shed” nesters. One pair (maybe more) lay eggs in a nest built on a workshop shelf containing jars of screws, up to twice each spring. Despite humans going in an out multiple times, the Thrushs’ are not daunted, continually flying in an out with food for their nestlings.

Figure: Grey Shrike Thrush each spring use an existing nest on a shelf in our workshop to raise one or two clutches. These birds have one of the most beautiful calls on par with magpies so having them around buildings is especially rewarding. Photo: Patrick Francis 27 October 2023.

Figure: Pasture renovation is not a deterrent to wildlife on Moffitts Farm. Here a young echidna explores the September sown chicory clovers pasture. There are plenty of ants, spiders and other insects living in the soil under the pasture. Photo: Patrick Francis 16 December 2023.