Dry summer and chain of ponds

Seasonal update Moffitts Farm February 2019

By Patrick Francis

While we started the 2018/19 summer with excellent prospects for finishing most of our August/September born lambs by the end of autumn, the lack of rainfall since mid-December has changed the outlook.

Early December rain was just what we were looking for to stimulate growth of brassica in two paddocks, and chicory/plantain/lucerne in another four paddocks. Lambs were weaned at an average age of 12 weeks onto mixed perennial grass species pasture paddocks. These contain summer active varieties of cocksfoot, tall fescue and brome grass so had enormous feed banks by Christmas. The summer active forage pastures were also growing exceptionally well and we set up a growth rate comparison trial with lambs on Mainstar brassica versus lambs on chicory/plantain.

When weighed after three weeks grazing the Mainstar brassica lambs were growing at an average 260grams per day while the chicory/plantain lambs grew at an average 240g/d. By early February there had been no effective rainfall since mid-December and the brassica’s palatability seems to have declined. After the second three weeks on the two pastures, the Mainstar brassica lambs had dropped to an average 210g/d while the chicory/plantain lambs had improved their average growth rate to 270g/d.

Figure 1: The dry two months in summer to mid-February has lowered brassica palatability and slowed lamb growth. Photos: Patrick Francis.

The decline in brassica palatability was confirmed when a second group of lambs were put onto a fresh ungrazed paddock. After 15 days they were weighed and there was no increase in their average live weight. These lambs were not eating the brassica and were maintaining weight eating the perennial grasses (which were being replaced in the pasture renovation) in and around the brassica sown area. I leave approximately 15% of renovation paddocks unsown, so livestock have grasses and clovers they are used to as they adjust to eating brassica which can in normal rainfall summers take 6 to 10 days.

Mainstar brassica is claimed by its breeder to be more palatable than Winfred which we had sown in other years. On this year’s experience we would disagree, but then Winfred may have had palatability issues during such a dry growing period. It is likely that low summer rainfall is the problem.

Rainfall in January was 10mm versus the average of 45mm. So far there has been 13mm up to 17 February versus an average of 48mm.

The low summer rainfall means that the brassica and chicory/plantain paddocks are not regrowing as normally expected. They won’t regrow until there is a 20 plus mm rainfall event and even then will require four to six weeks further rest. The implications are that finishing more lambs for delivery to Meatsmith will be delayed until mid to late autumn.

Figure 2: Chicory and to a lesser extent plantain plants have maintained their palatability but regrowth after lambs are removed has been minimal due to the lack of rainfall. Chicory has responded to grazing rest with a small amount of new growth possibly because it has a tap root. Photos: Patrick Francis.

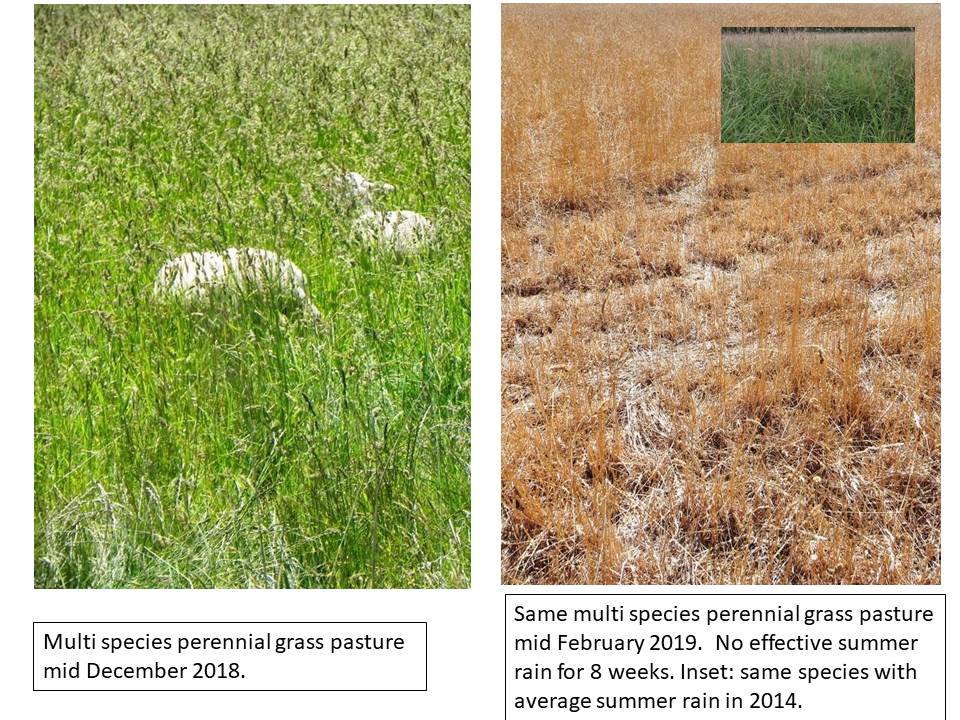

Most ewes are holding their condition on the dry pastures which are composed of a mix of summer active and summer dormant perennial grasses. Just as for the chicory/plantain the summer active perennial grass species stopped growing in early January. There will be no plant re-growth until a 20mm plus rainfall happens, Figure 3.

Figure 3: The 2018/19 summer has had so little rain that even the summer active perennial grasses have remained dormant. Photos: Patrick Francis.

Biodiversity

The early December rainfall produced an explosion of the forest brown butterfly population. Without more rain their numbers have declined and were rare to see in February. Echidnas have been common across the farm. Lowland Copperhead snakes and red belly black snakes have been rare on Moffitts Farm but this summer they have been spotted on a number of occasions. Interestingly the snakes have been well away from water, either the creek or dams. Given paddocks have high amounts of pasture cover the snakes presence is not surprising as skinks also live in the pastures.

Figure 4: Lowland copperhead snakes have been more common this spring and summer. Photo: Patrick Francis.

Chains of ponds

Sandy creek which runs through the farm stopped flowing in mid October 2018. After the early December rain while there was no run-off from the paddocks springs in the creek rose significantly about seven days after the rainfall event. This phenomenon is related to what is often referred to as “chains of ponds” creeks.

Figure 5: The water in this creek crossing was not from runoff, it started to appear seven days after early December rain which produced no runoff or flow in Sandy creek. It was generated from a spring adjacent to the crossing (on right) whose level rose as a result of subsurface flows into the spring adjacent to the creek. Photo: Patrick Francis.

The early explorers would often refer in their diaries to water ways as chains of ponds, because the actual creek floor was covered by native species grasses, forbs and wetland species, but where the water was deeper ponds would be present. Without livestock grazing the slopes adjacent to the creeks rainfall was absorbed by the soil so there was little runoff most of the time. The vegetation covered creek beds, figure 6, were protected from erosion as there was no exposed soil, and when rainfall was high the vegetation slowed water speed. The ponds were kept topped up via sub-surface drainage from the soil “sponge” in adjacent vegetation covered grasslands.

The creek lines we see today have mostly been gouged out due to livestock removing vegetation from creek floors and pugging up the floors and ponds, figure 7. The ponds were the only source of drinking water prior to dams being dug. The water way floors and sides had exposed soil and there was no vegetation to slow water speed. Adjacent grasslands were usually overgrazed so rainfall would runoff quickly into the creeks. Erosion was rife along the creeks beds and floors, hence the deep gouged creeks we see today.

In the last 30 years through the introduction of landcare programs, fencing off riparian zones from livestock, and increasing use of rotational grazing to ensure adequate levels of ground cover (1200kg dry matter per hectare) are maintained year round on paddocks adjacent to creeks, chains of ponds are returning on many water ways.

This has happened on Moffitts Farm with most of Sandy creek’s floor between the ponds (springs) covered in grasses. As well, all mixed species perennial pasture paddocks on Moffitts Farm carry a high load of pasture dry matter which when combined with high soil organic carbon (4 – 5% soil organic carbon) means all rainfall (except in extreme rainfall events – over 50mm in 24 hours) is absorbed by the soil sponge. When enough rainfall is absorbed it takes days or weeks to move by sub-surface drainage to replenish the creek ponds (springs).

Figure 6: Much of the Sandy creek floor through Moffitts Farm is covered with perennial grasses and wetland vegetation which regrew once livestock access was closed in 1994. This vegetation not only protects the creek floor and banks, it slows water flow and provides habitat for wildlife. The difference in height between the top of the bank and creek floor is unnatural and would have been caused by erosion of the floor and banks due to livestock damage since settlement in the 1840’s. The riparian zone has been further enhanced with trees and shrubs planted as tube stock and by direct seeding since 1990. Photo: Patrick Francis.

This phenomenon of creek springs or ponds filling up days or weeks after rain is characteristic of holistic grazing management which is being increasingly adopted by farmers across Australia’s higher rainfall pasture districts and pastoral districts.

Figure 7: Restoration of chain of ponds is happening on Moffitts farm. These two photos were taken at the same spot. The pine trees are still present but cannot be seen behind the native trees and shrubs. Photos: Patrick Francis.