Avoidable wildlife road kills continue unabated

By Patrick Francis

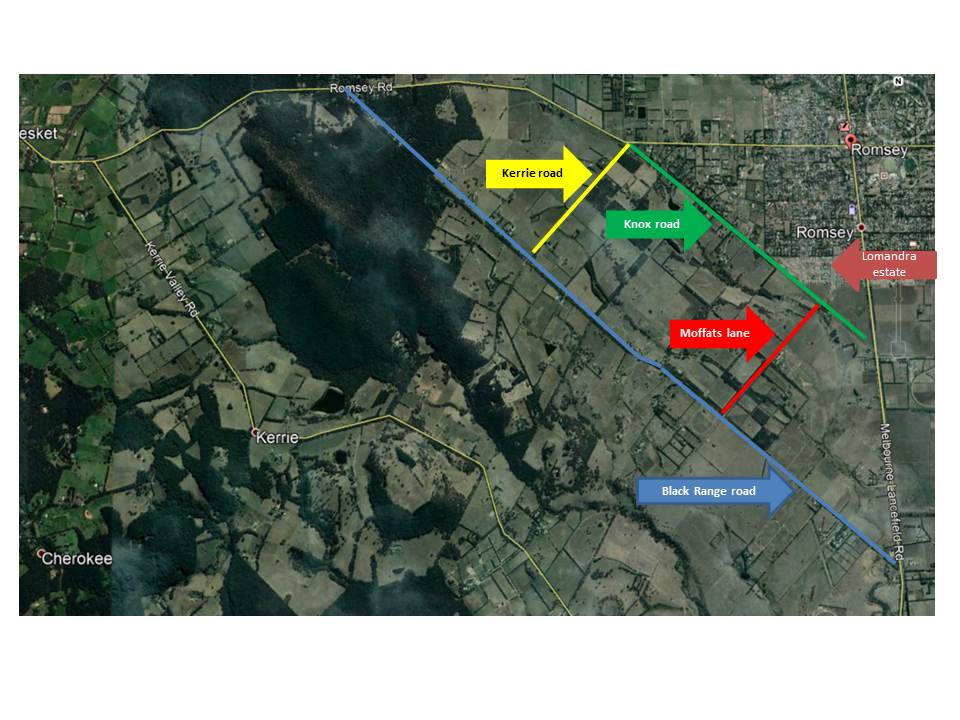

The 2020 summer/autumn period has seen an increase of wildlife road kills on minor rural gravel roads surrounding Moffitts Farm, Romsey, Victoria. Moffats lane and Black Range road have the state wide maximum speed limit of 100km per hour the same speed as the main highway between Melbourne and Romsey. It is difficult understand how our leaders in state and local governments can allow traffic speed laws to exist which are so inappropriate for public safety and wildlife on minor rural roads.

This maximum speed limit on minor rural roads makes there use by pedestrians, bike riders, and horse riders uncomfortable and even dangerous and is causing significant numbers of wildlife deaths among animals crossing and foraging on the roads.

These traffic speed laws on minor roads mean Victoria’s society is effectively declaring that public safety and wildlife protection is less important than vehicle drivers rights to reach their destinations in the shortest possible time. Put another way drivers convenience is the top priority on minor rural roads.

The increasing incidence of road kills begs the question about legal responsibility – does the vehicle driver have a responsibility to slow to an appropriate speed when circumstances suggest a high probability of collisions? As well, are local governments and Victorian government being negligent in not taking action to reduce driver speed on roads where there is a high probability of collisions? Should property developers be responsible for inappropriate road layouts adjacent to land with habitat that supports wildlife populations that are vulnerable to road kills due to their foraging and natural behaviours?

Landholders and farmers are not allowed to kill native animals such as koalas, echidnas, reptiles, and birds on their properties. Even pest populations of native animals such as kangaroos, wallabies and wombats require a permit from the state government for humane destruction and even for scaring them off the property. Killing and scaring without a permit is an offence with significant fines if found guilty. In contrast vehicle drivers can kill, injure and scare native animals that cross the roads in front of them without any consequences.

Another issue associated with road kills is whether or not the drivers involved are inflicting cruelty on the animals. Vehicle impacts are not an acceptable means of killing any animal, so if a driver takes no action to minimise possible impacts on roads where the presence of native animals is highly likely due to adjacent habitat, is that driver responsible for animal cruelty if an impact occurs? (See box story for relevant legislation in Victoria).

If drivers had the responsibility for protecting wildlife lives on minor rural roads then the maximum speed on these minor rural roads would be around 40km/hr. At that speed it is possible to see an animal moving onto the road and have the time to slow further or stop to avoid a collision or run over.

Certainly the maximum speed on minor rural roads will vary depending on the wildlife density in the adjacent landscape and the likelihood of animals crossing the road. In the Moffats lane Black Range road situation there are two significant reasons for a 40km/hr speed limit:

* Firstly, the western side of Romsey town abuts the Macedon Ranges which is haven for wildlife, figure 1.

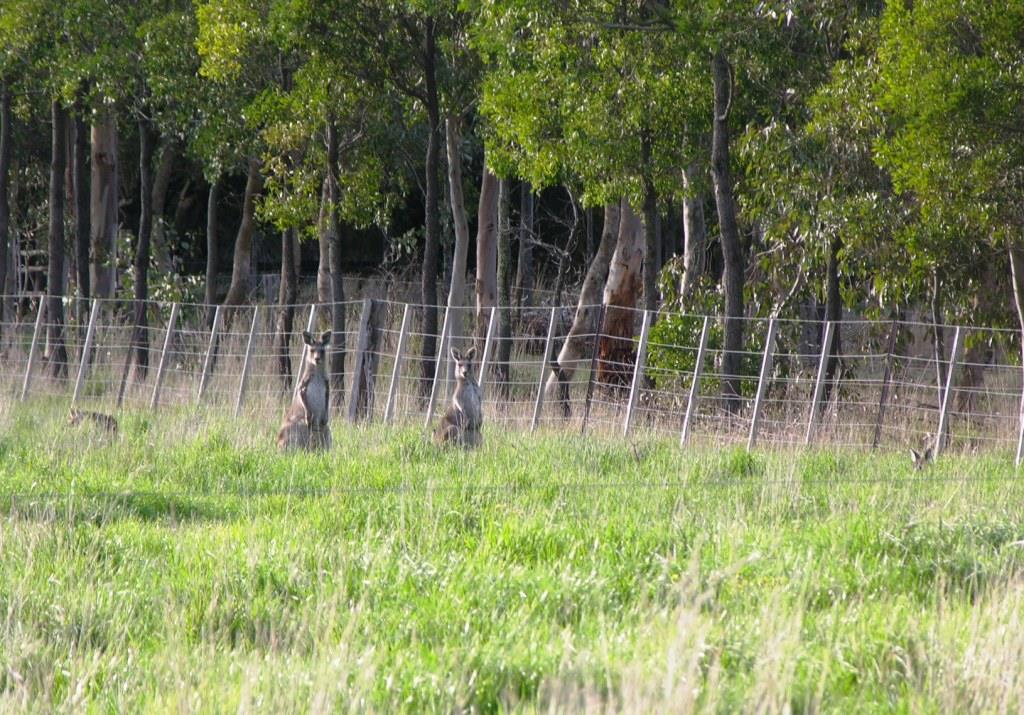

* Secondly, many of the farmers and landowners between Romsey and the Macedon Ranges have been actively revegetating their properties to provide habitat for wildlife, improve biodiversity and rehabilitate a previously cleared farming landscape. Some are active members of the Land for Wildlife program and results for wildlife rehabilitation in the area have been spectacular over the last 30 years, figure 2.

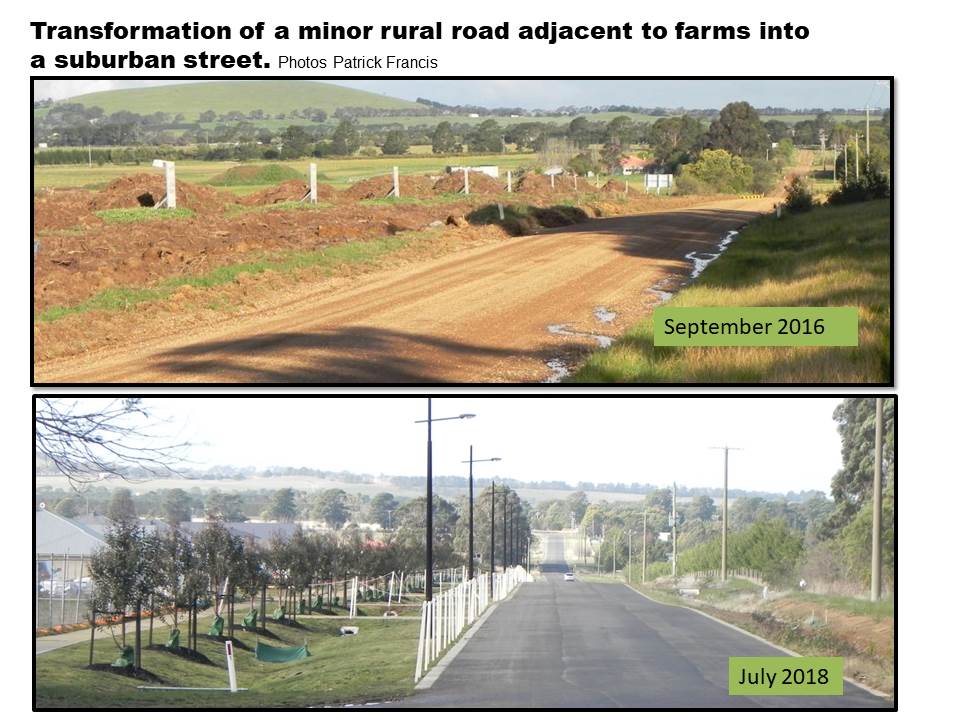

In the last five years a new phenomenon has emerged in our region which has increased the threat to wildlife on the minor rural roads between Romsey and the Macedon Ranges. Housing developments in Romsey and nearby towns have significantly increased the number of people living in the shire. This population increase is planned to continue for the long-term.

The housing development in Romsey has been the cause of significant increase in the number of drivers using Black Range road and Moffats lane. There are a range of contributing factors to why more road kills are happening because of increased population in the district:

* Most new residents have no appreciation or awareness of wildlife existence on and adjacent to minor rural roads so many are happy to drive at up to the maximum allowable speed, 100km/hr. Wildlife crossing signs seem to be ignored by most drivers as they are not accompanied by a legal speed restriction.

* Most new residents work in Melbourne or outer suburbs like Sunbury and because Romsey has no significant public transport, they virtually all drive to and from work or at least to the closest railway station at Clarkefield (15km to the south) every day.

* Many of the new residents drive large four wheel drive vehicles equipped with animal collision protection (bull bars) and have no fear of vehicle damage as a result of colliding with larger wildlife species like kangaroos, wombats, koalas.

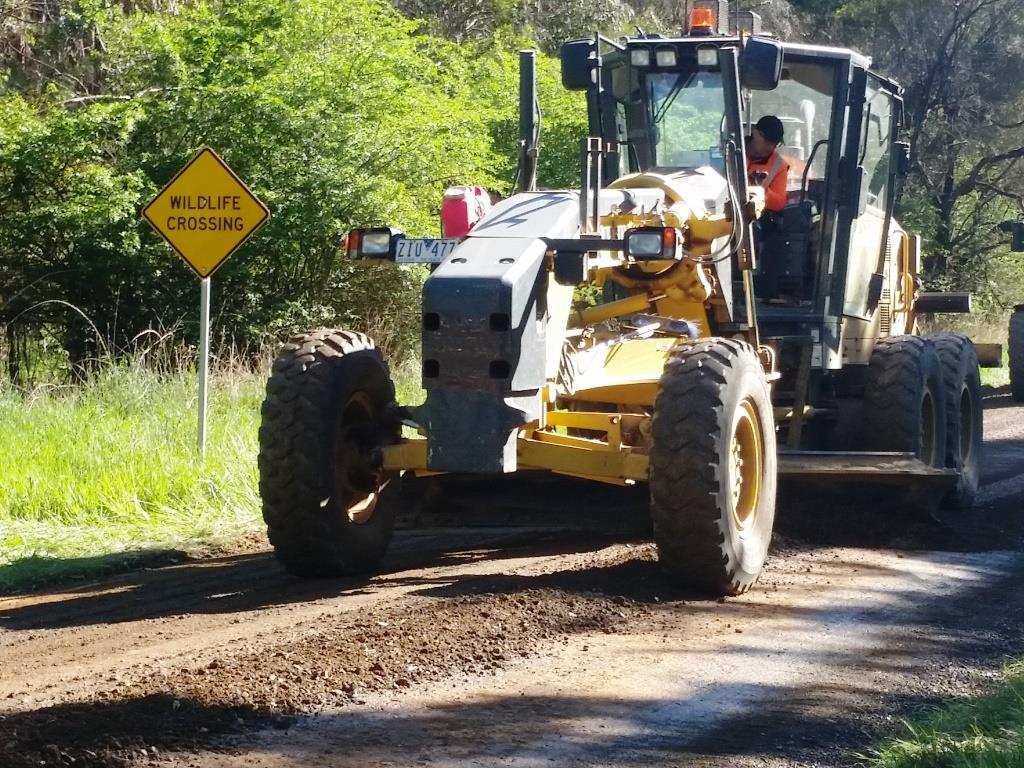

* The Macedon Ranges Shire has responded to complaints about minor rural gravel road surface conditions by engaging in regular gravel resurfacing and grading. This work has transformed these minor roads from relatively rough surfaces into extremely smooth surfaces encouraging drivers to travel faster. Annual independent surveys of how Victoria’s councils are performing in the opinion of rate payers contribute to pressure on minor road maintenance. The vast majority of rate payers live in townships and have no involvement with restoring wildlife on adjacent farms and public land. Their perception on what is desirable Council performance can be completely different to that of landholders and farmers who are encouraging wildlife back into their districts. So Council ensuring smooth gravel roads in the vicinity of a development may be a priority of new development residents but for the minority local landowners rougher roads which discourages high speed and saves wildlife is a priority. (As a rate payer in the Shire for 36 years I have never been asked to participate in this annual survey. Who is surveyed is a mystery, but the survey organisers ask no questions about wildlife welfare, support for conservation initiatives on private land, or support for agriculture in the shire.)

* The geography of Black Range road and Moffats lane in relation to Romsey township encourages the minor rural roads to be used by many new town and district residents as short cuts or “rat runs” . This has its genesis from inappropriate and wildlife safety negligent development planning on the edge of an existing township. Both roads allow for avoiding some of the township speed limits and or heavy traffic on the Romsey Melbourne highway. Black Range road provides a link to the west of Romsey to towns like Newham and Woodend without going into Romsey and being slowed by the 60km/hr limit. Moffats lane provides a link to the western side of Romsey town giving access at up to 100km per hour into the new Lomandra housing estate. The distance into the centre of the Lomandra estate is actually shorter going by the main highway than using Moffats lane, but the lower speed limit into town compared to 100km/hr on Moffats lane seem to encourage the use of the later route.

* The gravel surface of Black Range road and Moffats lane seems to encourage many drivers to adopt a rally mentality involving driving at high speed and leaving a heavy dust trail behind the vehicle. Even the large four wheel drive vehicle company advertisements promote such a rally driving approach. At the corner of Black Range road and Moffats lane a number of the ‘regular’ users skid from one road to the other in a cloud of dust.

The bigger picture

While there are particular circumstances surrounding increased use of Black Range road and Moffats lane, the issue of increased wildlife road kills and threat to public safety from vehicle speeds is widespread in the Macedon Ranges. For instance it is impossible to understand why the main road between Romsey and Woodend which also provides access to the major tourist attraction Hanging Rock, has a maximum speed limit of 100km/hr. Most of this road is adjacent to forest and significant wildlife habitat on farms to the west and north of the adjacent Macedon Ranges. Every evening kangaroos can be seen grazing in paddocks adjacent to the road along virtually it entire length. Magnificent manna gum, the favourite food of koalas grow in the paddocks adjacent to and along the road.

The road side is littered with dead wildlife but the maximum speed is 100km/hr!

The safety for humans on minor rural gravel roads is another important reason why maximum speed on them must be reduced.

The Lomandra Estate in Romsey demonstrates the issues involved. As a result of the increased population in the estate an increasing number of residents are taking advantage of nearby natural environment and opportunity to see wildlife by walking and cycling along Moffats lane and other nearby roads which link to the Macedon Ranges. In fact an exercise/nature walk circuit seems to be developing by leaving the estate along Knox road, Moffats lane, Black Range road and Kerrie road back to Knox lane and into the estate, figure 1.

The people using the circuit must share the road with vehicles which can be travelling at up to 100km/hr. The pedestrians, cyclist and often pets are not only under threat from collision but also from stone injuries as vehicles drive past at speed.

Another threat of the 100km/hr speed limit is the danger it poses to other drivers, especially residents on the roads concerned. Many of us, especially landowners who value the return of wildlife to their properties will drive at 40km per hour to ensure the safety of animals and pedestrians. We are now under threat of road rage from users who want to travel at the maximum speed. Even turning into or out of our front gates or moving farm machinery from one property to another along these roads is becoming hazardous and stressful.

Tailgating is common amongst higher speed drivers who become annoyed at slower speed drivers.

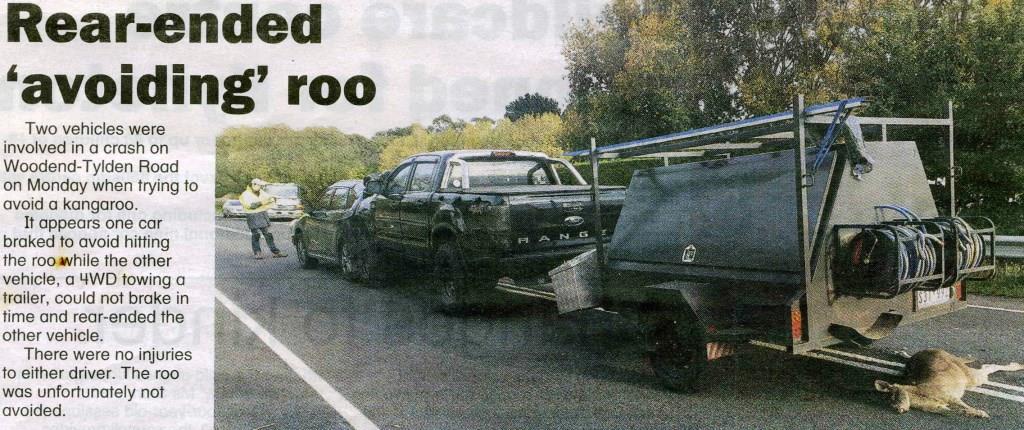

Vehicle drivers with empathy for wildlife will drive at speeds they feel are safe to avoid collisions, often 40 – 60km per hour on minor rural roads and connecting bitumen roads. But drivers with no empathy or awareness of avoiding wildlife road kills and injuries often drive at the maximum allowable speed of 100km/hr. The two approaches are incompatible and are contributing to vehicle collisions, aggressive driving such as tail gating and unsafe overtaking and road rage. Without government policy to align vehicle maximum speed limit with potential for wildlife collisions on specific rural roads in peri-urban areas the conflicts between drivers will escalate as populations increase throughout the region. Photo: Midland Express 21 April 2020

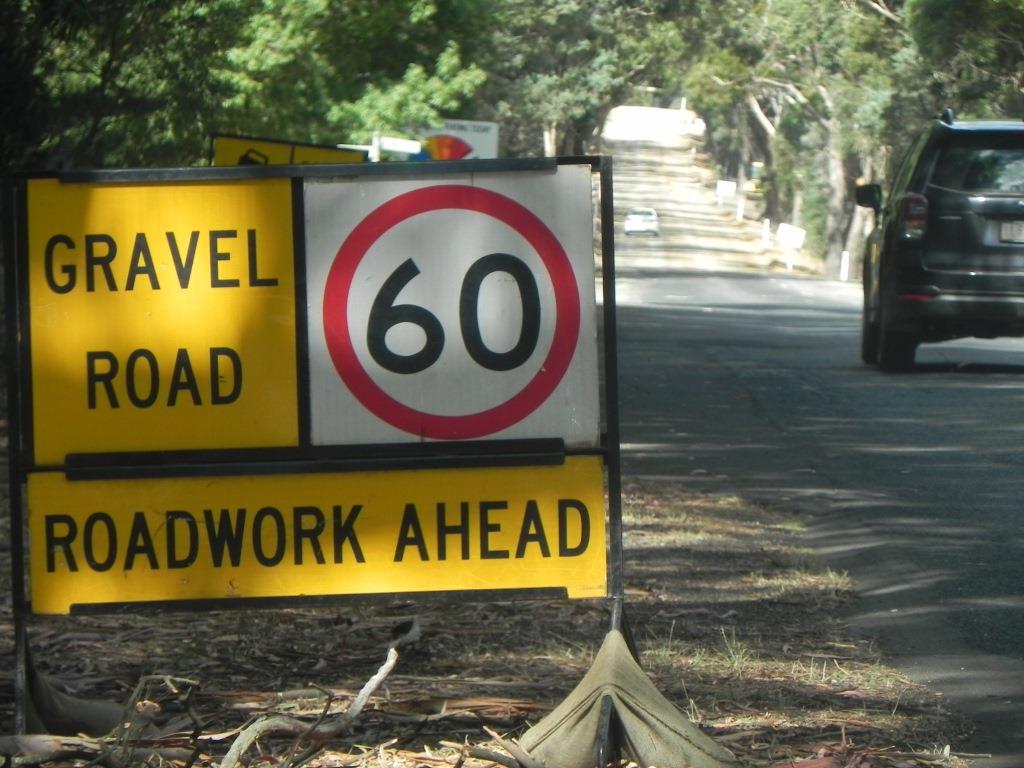

Given how obvious the reasons behind road kills are it is difficult to understand why local and the state governments cannot see and act on the risks involved. Governments response are highly contradictory. Take road works on main roads. When a new surface is being prepared, speed limits are reduced to 40km per hour, presumably to protect workers and drivers because there is more danger on the gravel surface. Even when the gravel surface is fully prepared and waiting for a bitumen surface the speed limit is capped at 60km/hr. Yet single lane, comparatively looser surface minor gravel roads with vegetation and single vehicle creek bridges have a 100km/hr speed limit.

Local government response

The issue of high vehicle speeds on local government controlled roads (minor rural and township) is widespread across the Macedon Ranges shire. It has a population growth policy for small towns with competing interests among residents for access convenience and comfort versus improved biodiversity and safety. So far the Council has generally been reluctant to seek methods for controlling speed on local rural roads. My requests for intervention over the last two years have been meet with reasons why nothing can be done other than erecting sign posts such as “Wildlife crossing” and giving general advice to motorists to travel at a speed which “suits the conditions”. Both have no effect on reducing speed.

However, a meeting with two Council staff in February heralded a possible breakthrough when it was agreed the Council could engage with the State government to look at introducing lower legal speed limits on particular minor rural roads. The local state member Mary-Anne Thomas has taken an interest in the topic and has also suggested to the Council that it needs to take some initiatives to have local speed limits applied to particular roads. Up to this February meeting the Council’s response to calls for lower speed limits on local roads was that issue was under state government control and it had no say. According to Thomas, local government has a role in lobbying state departments for change to take place.

Planning laws for new estates need overhaul

As more people move into new housing developments in peri-urban Melbourne there will be increasing conflict between wildlife and humans. The conflict is most apparent in the shires which have natural landscapes and vegetation which support wildlife and is particularly apparent in the Macedon Ranges. In comparison Hume shire to the south has fewer concerns with this interaction.

Nature and society

In the bigger scheme of life on earth, the issue of road kill has important implications for the type of society we want for future generations. At the moment society via its governments in Victoria seems to be saying that on minor rural roads driver convenience has a higher priority than wildlife injury and deaths and this should be preserved with speed limits determined to meet the safety of the drivers. There is currently no policy for determining maximum speed limits based on the level of threat to wildlife living on and adjacent to these roads.

The irony of this acceptance of road kills is that when natural disasters happen such as major bushfires that impact wildlife causing injuries and deaths there is enormous public sympathy for the animals. During and after the 2019/20 bushfires millions of dollars were donated by the public to help care for affected wildlife. Outside the bushfire affected areas public concern about daily road kills and injury is virtually non-existent except amongst wildlife carers. The only publicity for wildlife on roads relates to the number of road accidents which may result in humans being injured or killed. As well, animal impacts with vehicles are reported annually based on the number of insurance claims for vehicle repairs. Such reporting makes no connection with driver speeds involved or avoiding collisions in the first place by slowing to a safe speed on roads frequented by wildlife.

In NSW and Queensland there are initiatives in place to have koalas included on the endangered species list as so many have been killed by fire and loss of habitat. Ecologists talk about local extinctions happening. But prior to the fires there was no publicity around koala and other native animal road kills happening every day, many on minor roads where the impacts can be avoided

The Macedon Ranges in Victoria has a small and declining koala population, there is no doubt it is endangered (local population census are no longer being undertaken, the last was about 10 years ago). Many farmers and land owners through their own initiative or in conjunction with landcare groups are making significant steps towards halting the koala population decline by restoring habitat, particularly their staple food manna gums. But road kills undermines their efforts. Do the koalas have to wait until the next major bushfire happens in the Macedon Ranges before the public becomes aware of the perilous state of its population? Such a natural catastrophy is likely to be too late for these animals preservation.

Take home messages

Road kills of native animals are avoidable on minor rural roads in the Macedon Ranges and adjacent shires. To achieve this traffic speeds on these roads must be legally limited to a maximum of 40 km/hr. State and local governments need to change road speed policy from one which only protects the convenience of drivers to one which also protects wildlife.

Drivers can no longer be excluded from fault for injuring and killing wildlife on minor rural roads based on the assumption of misadventure on the part of the animals crossing in front of their vehicles. Drivers have to become accountable for native animal deaths and injuries when there is clear evidence that animals use road verges and adjacent land and riparian areas as part of their natural foraging and social ranges.

Driver penalties should be introduced for killing and injuring native animals on minor rural roads as a result of excessive speed in a similar way as penalties exist for unlawful killing or cruelty to animals under existing biodiversity and animal welfare laws.

State and local governments need to be proactive in reducing maximum speed limits on major roads where wildlife are plentiful in adjacent land. This may be full-time speed restrictions or timed restrictions such as from dusk to dawn. Simply erecting signs warning large wildlife are likely on the roads is not sufficient instruction to drivers, they must be accompanied by an appropriate legal speed limit which depending on the road type will avoid or minimise impacts.

Planning policy for housing developments in peri-urban Melbourne (100km radius) where wildlife populations already exist and/or are increasing due to landcare revegetation initiatives on adjacent land, must be changed. Developers must be required to protect wildlife from death and injury from inappropriate road layouts and increased traffic on minor local roads which are not part of the development.

Note: Most road kills are out of sight and out of mind to most peri-urban drivers unless they result in damage or injury to vehicles and drivers. The vast majority of kills are small animals and birds which soon disappear off the roads, usually taken by foxes. Even kangaroo carcases do not last long as they are food for foxes. Foxes are the major predator of small native animals in Victoria. Not only are road kills directly reducing numbers of wildlife they indirectly contribute to small animal predation by increasing fox populations.

Box story

Road kills emotional impact on Land for Wildlife farmers and rescuers

The impact of vehicle road kills and injuries from collisions with vehicles is currently only recognised through incidents causing injury to humans and damage to vehicles monitored by insurance companies and automobile clubs. As yet no state or local governments seem to recognise the emotional impacts wildlife road kills and injuries have on the farmers and landholders who make the effort to protect or reinstate wildlife habitat via biolinks, riparian zones, and forestry across their properties.

This is surprising given the Victorian government actually sponsors the Land for Wildlife program which currently has around 12,000 members across approximately 5000 properties and more than 530,000ha of private land.

Land for Wildlife has multiple conservation objectives but as its name suggests one of these is to “provide links between nature reserves, allowing for wildlife movement and genetic interchange”. And its wildlife movement from habitat adjacent to and along roads particularly minor rural roads which bring animals and vehicles into a collision zone.

When landholders have this objective by protecting or enhancing habitat on their properties they simultaneously develop a close empathy with the wildlife living in or passing through it. To find this wildlife dead or injured on roads is an emotionally distressing event. The distress is heightened by lack of government policy to minimise the possibility of road kills by changing legal maximum speed limits. Landholders feel let down by a policy framework which outwardly advocates for greater conservation effort to protect wildlife but fails the wildlife by preventing their greatest anthropogenic threat – vehicles travelling at speeds which make collisions virtually unavoidable.

One research investigation has provided a sense of the emotional impact of road kills.” A review of roadkill rescue: who cares for the mental, physical and financial welfare of Australian wildlife carers?” by Bruce Englefield et al found that a serious problem is emerging amongst volunteers.

“A perceived lack of understanding, empathy and appreciation for their work by government can add to the stressors they face. Volunteering is declining in Australia at 1% per year, social capital is eroding and the human population is aging, while the number of injured and orphaned animals is increasing. Wildlife carers are a strategic national asset, and they need to be acknowledged and supported if their health and the public service they provide is not to be compromised.”

The same can be said about many Land for Wildlife participants especially those in peri-urban areas like Romsey who are continuously exposed to the unnecessary deaths or threat of death to the wildlife they nurture. The emotional stress from the threat of wildlife death is nearly as bad as the deaths and injuries themselves.

100km/hr vehicle roar is threatening

This emotional threat is present 24 hours a day to landowners adjacent to roads like Black Range road, Moffats lane, and Knox road, see figure 2. That’s because this stress is manifested in the roar, heard from up to one km away, of vehicles travelling at 80 – 100km/hr. Every time the roar approaches, landholders with empathy for wildlife wonder if the animal they have recently seen foraging in a conservation zone has wandered onto the road and is about to be hit by the on-coming vehicle. That emotional stress is relentless day and night, wet or dry and it manifests itself across all wildlife species, not just the iconic ones.

The emotional stress for Land for Wildlife property owners from vehicles travelling at speed on adjacent roads is continuous as they know the wildlife on their properties could be roadkill at any time. This echidna is foraging in a riparian zone just 30m from Moffats lane, vehicles can travel up to 100km per hour on the narrow gravel lane. Photo: Patrick Francis February 2020.

Englefield’s research backgrounds the possible extent of road kills in Australia.” The complexities of multiple spatial and temporal variables in the available data on Australian roadkill and the scale of orphaning and injury make statistical analysis difficult. However, data that offer proxy measures of the roadkill problem suggest a conservative estimate of 4 million Australian mammalian roadkill per year. Also, Australian native mammals are mainly marsupial, so female casualties can have surviving young in their pouches, producing an estimated 560 000 orphans per year.”

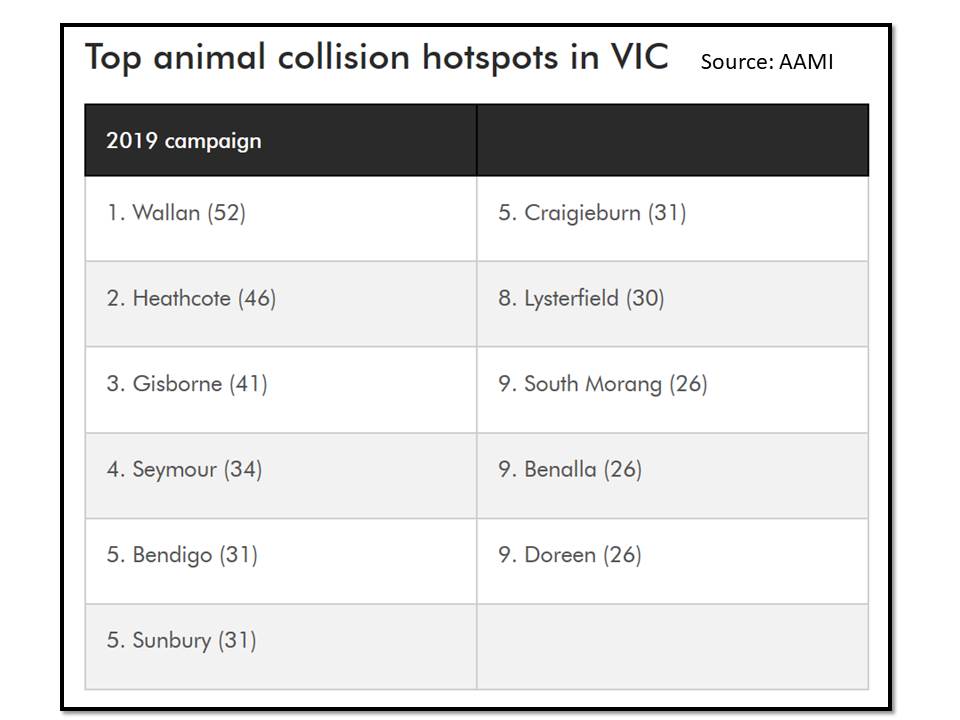

Specific data on vehicle insurance claims after impacts with wildlife is published by some insurance companies. AAMI produces an annual report into its claims. In its May 2019 report it noted: “VIC has had back-to-back dishnourable wins for having the country’s highest rate of animal collisions, with 3,673 AAMI claims. That’s 779 more than NSW, which had the second most claims with 2,894.”

The report tabulated state wide hot spots for animal collision claims. For Victoria it is not surprising that five of the 10 hotspots are in the peri-urban area and most are council areas north of Melbourne, table 1.

It should be remembered that the data in Table 1 only reflects claims made to AAMI by its clients when they have damage to vehicles. Animal collisions made by vehicles equipped with bull bars and don’t incur physical damage but leave wildlife dead or injured will not be reported.

References:

Land for Wildlife www.wildlife.vic.gov.au/protecting-wildlife/land-for-wildlife

Bruce Englefield et al Wildlife Research 45(2) 103-118 published: 4 May 2018

AAMI animal car accidents data 2019, May 2019.

Victorian Legislation

Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (POCTA) Regulations 2019

“Overview: Animals are important to Victorian communities and have a valuable role in our economy. They are part of Victorian homes, farms, sport, recreational businesses and activities, natural state, research and essential services.

The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Regulations (POCTA Regulations) protect the welfare of animals in Victoria by supporting requirements set under Victoria’s primary piece of animal welfare legislation – the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act 1986 (POCTA Act). The new Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (POCTA) Regulations 2019 commence on 14 December 2019, replacing the previous POCTA Regulations 2008.”

These new regulations make no references to road kills and responsibility for them.

Wikipedia makes an important point about categories of animal cruelty: “Animal cruelty can be broken down into two main categories: active and passive. Passive cruelty is typified by cases of neglect, in which the cruelty is a lack of action rather than the action itself. Often times passive animal cruelty is accidental, born of ignorance.”

Road kills usually fit this passive cruelty definition.

Wildlife Act 1975

“1A Purposes The purposes of this Act are— (a) to establish procedures in order to promote— (i) the protection and conservation of wildlife; and (ii) the prevention of taxa of wildlife from becoming extinct; and (iii) the sustainable use of and access to wildlife; and (b) to prohibit and regulate the conduct of persons engaged in activities concerning or related to wildlife.”

Road kills caused by excessive vehicle speed along roads surrounded by verges, land and riparian zones with recognised wildlife populations would seem to contravene part 1A of the Wildlife Act 1975. Koalas in the Macedon Ranges are vulnerable to extinction with road kills being a major contributor.

The Act outlines significant penalties for contraventions: “Hunt, take or destroy protected wildlife without an authorisation, 50 penalty units or 6 months imprisonment, or both; and 5 penalty units per head of wildlife; $805.95 per head of wildlife.”

The Act also contains provisions for disturbing protected wildlife: “Disturbing protected wildlife without an authorisation; 20 penalty units, $3,223.80.”

Ironically the Act does not refer to the words “road kill” indicating there is no offence involved with killing native animals on public roads with a vehicle even if it is avoidable such as by driving at a slow speed. As well there is no reference to vehicles as an instrument for killing and/or disturbing native animals.

We had to call Wildlife Victoria to euthanize a kangaroo on Moffats Lane. The poor thing was spooked by cars and tangled itself in the barbed wire on a fence. It was suffering so much, with a broken hip and scalped foot. We walk along the dirt roads in the area and cars don’t slow down past us, kicking up stones and driving dangerously close. It’s a disaster waiting to happen. It makes no sense that Knox Rd is 80km/hr but a dirt road next to it is 100km/hr. My partner and I wholeheartedly support your efforts to reduce the speed in these roads. It is frankly negligent for council to ignore this issue. It’s so heartening to know that people are pushing for this. Keep fighting the good fight!