What makes a regenerative agriculture farmer

Comment by Patrick Francis

Over the last three years a “new” term for methods to advance Australia agricultural practices has become increasingly used, its called regenerative agriculture (RA) and those practicing it are called regenerative farmers. The term has taken over from descriptions like holistic farming, landcare farming, conservation farming, sustainable farming and even some organic farmers call themselves RA organic farmers. Many public farming extension and support organisations like landcare groups, catchment management authorities and departments of agriculture now promote and advocate regenerative agriculture.

In the private sector new organisation and businesses have emerged carrying the regenerative agriculture name as part of their brand. Journalists across all forms of the media constantly profile or report on people who refer to themselves as RA farmers.

But what is regenerative agriculture and how is it distinguished from other forms of farming practice?

Is it a superior form of farming based on social, environmental, productivity, climate resilience, animal welfare and food safety grounds? Are its practioners certified or recognised by any audited process to verify their farming methods achieve any particular ecosystem functions outcomes not achieved by best practice conventional farming management or provide particular consumer assurances around food production and animal welfare as with certified organic farming or in an environmental management system?

The answers to these questions are possibly yes and possibly no. Any farmer can claim she or he is a regenerative farmer, just like they can claim they are sustainable, holistic, and even organic. And there are many farmers who could claim these methods but prefer not to do so as their preferred brand is simply “farmer”. An increasing number of farm consultants claims their advice is based around regenerative agriculture principles, while retailers of “natural” soil health inputs infer their products are compatible with RA.

One New Zealand regenerative agriculture consultant, Nicole Masters, Integrity Soils, highlights the variable interpretations involved when she says on her web site that “Regenerative Agriculture is also known as Biological Agriculture, Holistic Ag, Ecological Agriculture, Natural Intelligence, Eco-Agriculture, Natural Farming, Humus/Carbon Farming…. There are no silver bullets here or one road to Rome, but programs based on observation, ecological principles and regenerative land management practices. It covers a wide range of approaches, tools, and the thinking required to build soil and ecosystem health, food quality, and profitability. You can call it what you want. We call it common sense.”

What Masters omits from her RA definition is any association with agricultural science. This is a common occurrence.

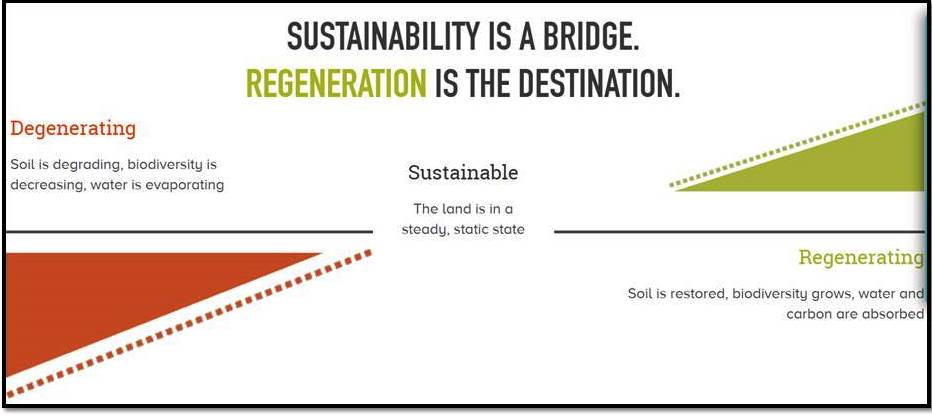

One of the easiest to understand interpretations of what regenerative agriculture is all about is provided in a diagram on the Savory Global website promoting its Ecological Outcome Verification (TM) program. It shows that grazing practices can be degrading the health of the land as a living system, sustaining it or regenerating it, figure 1. The indicators used to measure land health are soil health, biodiversity and ecosystem functions.

Figure 1: The Savory Global depiction of what land regeneration is about. Source: Savory Global website.

The outcomes of regenerative agriculture methods just like best practice conventional farming methods are positive but highly variable for a host of issues including ecosystem functions across farms, biodiversity, soil health including soil organic carbon level, animal and crop productivity, livestock welfare, enterprise resilience in the face of climate change, and the well being of farmers involved.

But brand regenerative agriculture has issues which are not readily apparent especially to less experienced farmers. These stem from the way the brand is interpreted by its wide range of its champions who are a minority of farmers, ag consultants, input suppliers, environmental academics, food and fibre businesses and medicos.

The adoption of RA amongst mainstream professional farmers over time might have been a fairly straightforward process if not for one barrier, the associated ideology promoted by its champions that conventional farming methods and the agricultural scientists and technologists involved with its research and extension are responsible for land and water degradation and for producing food which is less healthy, possibly toxic, and is responsible for the decline in human health around the world. As a consequence instead of being a methodology for positive change it has become a cause of division amongst farmers. The major divisions centre around accusations:

* That agricultural science based farming practiced over the last forty years is degrading farm ecosystem functions. This type of farming is often referred to as intensive, industrial or factory farming.

* That agricultural scientists involved in research and extension have had no interest in improving ecosystem functions and have focused solely on productivity and profitability. These scientists have been manipulated by the multi-national agricultural chemical companies who have become increasingly responsible for research and extension funding as their traditional funders, state governments, have withdrawn their financial support for agriculture.

* That conventional farming using artificial inputs such as herbicides, insecticides and chemical fertilisers is decreasing food’s nutritional quality as well as contaminating it with toxins causing significant health problems for humans.

* That conventional farming and conservation methodologies have not changed significantly over the last 30 – 40 years to ensure ecosystem functions are being maintained or improved where needed.

* That within livestock grazing regions, natural or unchanged environments (as close as possible to pre-1788 status in Australia) have higher ecosystem function quality than environments changed to any extent by introduced species and inputs.

* That the only ‘responsible’ farmers are the small groups of people who contend they practice regenerative agriculture. This distinction has widened in the last few years into an ideological divide for some RA champions who claim some sort of moral and ethical differences between how they farm and how the majority farm.

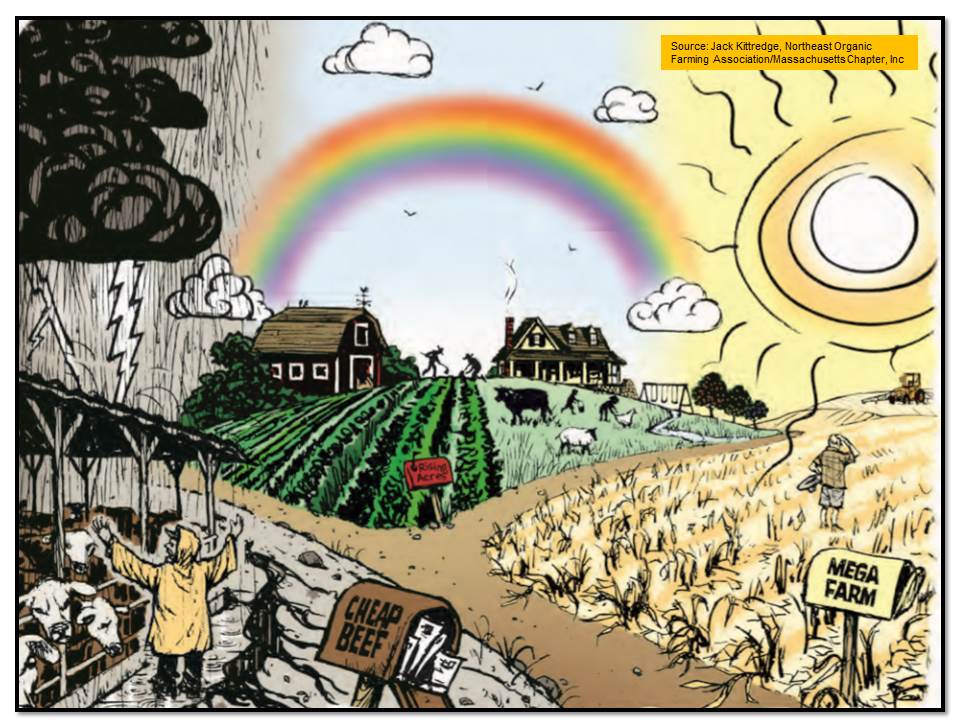

The ideological distinction – good versus bad farming, is clearly portrayed in the front cover illustration from a book promoted by Regeneration International as what RA is all about, figure 2A.

Figure 2A: Some parts of the regenerative agriculture movement are deliberately creating a division between farmers based on their approach to management. In this illustration the RA organic farm is green with a happy family working and playing in a pleasant environment. In contrast, the cattle feedlot manager (left) portraying factory farming, is throwing his hands up in despair as flooding rain causes effluent to runoff from the pens stocked with miserable cattle. On the right, the ‘mega’ or industrial cropping farmer is scratching his head as drought withers his crop. Source: Jack Kittredge, Northeast Organic Farming Association/Massachusetts Chapter, Inc

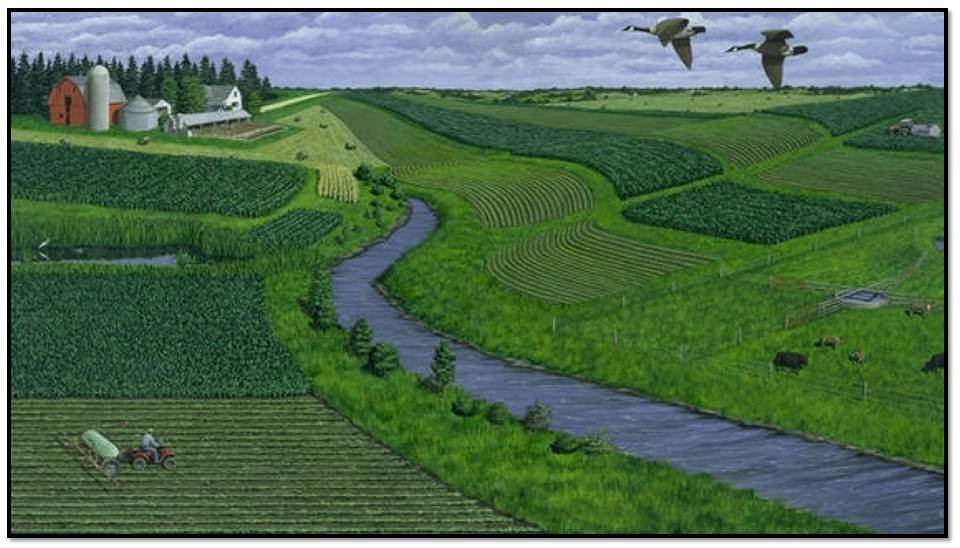

In contrast to this illustration the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Services illustrates its August 1999 Conservation Practices Training Guide “The Common Sense Approach to Natural Resource Conservation” with a farming scene embracing all the benefits of agricultural science based farming, figure 2B. The scene is strikingly similar to the RA farm in the centre of figure 2A. The words “common sense ” are just what Nicole Masters uses in her definition of RA.

Figure 2B: This 1999 illustration of holistic management based on agricultural science is used by the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service to describe a “common sense approach” to farming.

Having different views and opinions is positive for achieving improvements in all aspects of human endeavour, the danger comes when one line of thinking provides an illusion of superiority over others.

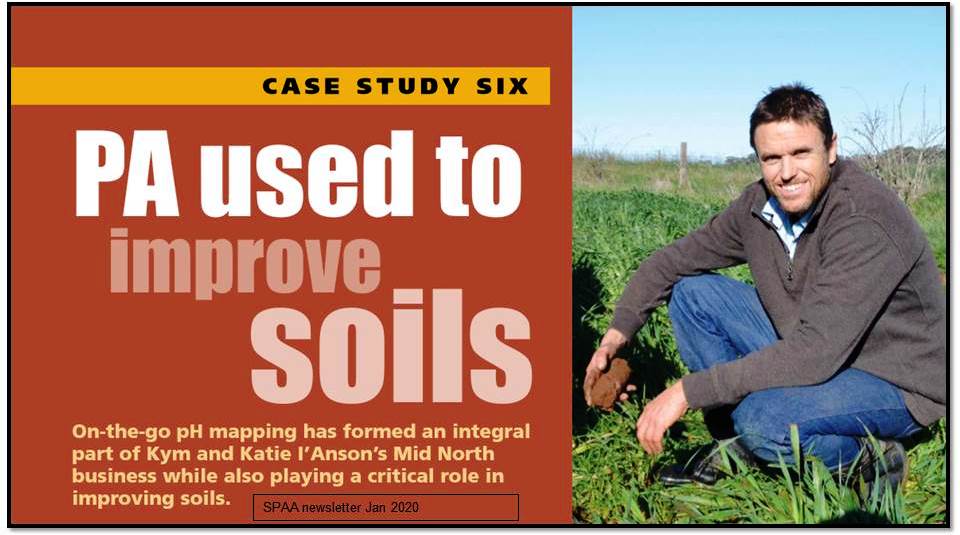

Figure 3: This SA farmer contends that precision agriculture is improving his cropping soils and business profitability but the methods used would be described by some RA champions as industrial agriculture causing ecosystem decline and harming human health. Such generalisations are made based on ideology not science.

Before the regenerative agriculture brand became popular over the last five years, the only significant divisions in farming methodologies were between conventional, holistic and organic. The distinction between organic farmers and the rest was straightforward because organic farmers had about six national and various overseas certification bodies which set the rules for involvement. There were no exceptions, farmers accepted the rules based mainly around acceptable and unacceptable inputs and livestock management to achieve certification.

The holistic methodology emerged through the 1990’s and was adopted by farmers who had a strong focus on managing farm ecosystem functions as well as profitability. It grew in popularity amongst livestock grazing farmers in Queensland and NSW who adopted cell grazing. There was no certification involved to provide farmers or food consumers with guidelines as to what was involved or what were acceptable inputs as per organic farming certification. It is reasonable to conclude that the regenerative agriculture movement had its genesis in holistic farming and for many farmers the distinction is blurred.

There was one other farming environmental movement in recent decades which grew out of the awareness that consumers wanted to know more about farmers’ attitudes towards ecosystem functions, animal welfare and food safety. It was the Environmental Management System (EMS) approach to managing the entire farming system and providing documented evidence based on best practice science that constant improvement was taking place or was being maintained at a high level.

This movement was strongly supported by the NSW Agriculture and trial programs were run in the late 1990s and 2000s by the likes of Meat Livestock Australia, Grains Research & Development Corporation, Victorian Farmers Federation, farmer groups such as the Migenew-Irwin group, and Gipps Beef, figure 3.

Figure 4: The Environment Management System method of demonstrating continual improvement for across farm ecosystem functions, animal welfare and food safety has been mostly ignored by farmers as involving too much paperwork for little gain. Exceptions are Red Tipped bananas and Enviromeat.

In 2002 Federal and State Ministers endorsed a National Framework for Environmental Management Systems. Subsequently the Federal government created the National EMS Program followed by the National Pathways to EMS program.

EMS did not capture the imagination of most broadacre farmers and NRM agencies, mainly because the system requires an on-going commitment to evaluation, in contrast government programs and governments themselves have short-term life spans of three to four years.

A few small programs continue on so the farmers involved have a fully documented method of assuring their customers that what they say is being done to look after the holistic health of the farm is actually taking place on a continuing basis through annual reviews and auditing. EMS adoption could lead onto a farm becoming compliant for ISO 14001 environmental certification. The last step is onerous and expensive and very few farm businesses have followed it through.

The Australian Land Management Group’s Certified Land Management (CLM) system was one EMS based program that managed to achieve enough farmer participation to operate for 15 years from 2000 to 2015. It functioned without being judgemental about the way farmer’s operated. “CLM is user friendly and takes account of the land manager’s capabilities and aspirations. Land managers use CLM to develop their own plan for improving natural resource management, animal welfare, productivity and risk management. With CLM land managers can verify their environmental and animal welfare credentials. Accredited auditors review implementation of the management plans, ensuring the integrity of the certification.

Beyond organics

Organic certification takes a holistic approach across the farm environment, animal health and welfare and food and fibre quality. It is somewhat surprising that some RA champions refer to their approach being “beyond organic”. One organic based farming group in the US, the Rodale Institute, believes there is a place for a higher level of certification above organic and has started Regenerative Organic Certified. It’s web introduces the program by stating “We’re beyond the point of sustainability and we need to regenerate the soil and land that supports us, the animals that nourish us, and the farmers and workers that feed us.”

At first glance it seems this program is similar to those offered by existing organic farming certification with sentiments that should be universally applied across all farming methods. But this program takes certification to a new level as it requires certification at three management points, figure 4. These point are:

* Soil health – associated with existing organic certification program

* Animal welfare – which requires additional certification from an animal welfare organisation

* Social fairness – which requires additional certification from a fair trade organisation.

Once all three are achieved the farm can be Regenerative Organic Certified. The additional certifications over organic are not confined to any farming method and some conventional farmers have been participating in them for many years.

Figure 5: The regenerative agriculture program run in conjunction with the US Rodale Institute has introduced a three component certification program called Regenerative Organic Certified. To be eligible the farm must gain certifications for organic soil health, animal welfare and social fairness. Source: Regenerative Organic Certified web site.

In 2019 a monitored and audited program surrounding regenerative agriculture practice for livestock and mixed farming business has been introduced by the Savory organisation in USA, its called called Ecological Outcome Verified (EOV™). The program is described on its web site as “EOV™ measures and trends key indicators of ecosystem function, which in the aggregate indicate positive or negative trends in the overall health of a landscape.”

Measuring and monitoring ecosystem function trends over time seems to be a key difference between EOV™ and other environment management programs and even certified organics. The latter are based on procedures, allowable inputs and checklists rather than monitored eco-function outcomes. Trend data is critically important to know as in biological systems there is a great deal of variation from year to year but if practice change is introduced, over the medium to long term positive trends will be uncovered if nature allows it.

Monitoring ecological trends also helps farmers understand that equilibrium exists in nature. For example one of the most used accusations by RA champions is that soil organic carbon levels have been depleted by farming/grazing management. There are many grazing farms with long-term perennial pastures under holistic management where soil organic carbon has reached equilibrium.

This example also raises what is likely to be an issue with EOV™, that is cost associated with constant auditing by a third party. Most farmers involved in holistic management and who monitor outcomes learn from their own experience what is improving ecosystem functions while maintaining or increasing productivity if desired. Auditing can become a cost burden unless it is offset by access to particular food and fibre markets which pay for it. Most farmers practicing holistic management receive their reward be it monetary or otherwise from the positive ecosystem functions, animal welfare outcomes, food and fibre quality , and lower costs of production involved.

What does regenerative agriculture mean?

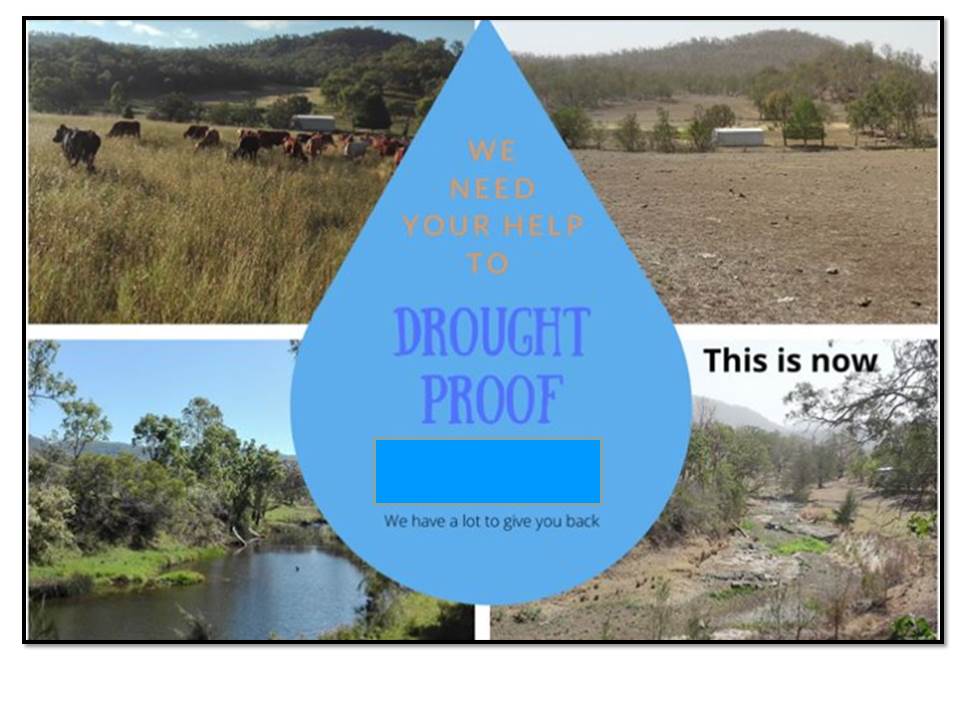

A classic example around the confusion created amongst farmers and possibly food consumers by the regenerative agriculture label appeared on one farm’s Facebook page in December 2019. The farmer who claimed to be regenerative and organic had launched a crowd funding campaign to help the business survive the drought. The photos used to highlight the state of the property before the drought and in the drought suggested that the grazing management involved was not industry accepted best practice – an outcome too often seen across grazing management systems, figure 5. Lack of pasture cover means ecosystem functions are being damaged.

Figure 5: The term regenerative agriculture is now being widely used by farmers but some seem to have little understanding of the holistic management involved.

This is a simple example to highlight how farming methodology labels without holistic understanding and monitoring data can be misleading or irrelevant.

Term origin

The term regenerative agriculture originated in the US when the Rodale Institute, an organic farming research organisation began using it. Robert Rodale defined Regenerative Agriculture in 1983 as a method ‘that, at increasing levels of productivity, increases our land and soil biological production base. It has a high level of built-in economic and biological stability. It has minimal to no impact on the environment beyond the farm

or field boundaries. It produces foodstuffs free from biocides’.

In Australia the term has been around for many years after ecologist Dr Christine Jones began using it in the 1990s. She used it in relation to rebuilding soil health and subsequently improving ecosystem functions across the farm and preferred it to the word ‘sustainable’ which could infer maintenance of status quo rather than improvement.

A review of regenerative farming history by Ken Giller et al published in 2021 found that the term only became commonly used after 2016: ” While the terms Regenerative Agriculture and Regenerative Farming have been in use since the early 1980s, to date they have not been as widely used as other

related terms such as sustainable agriculture or organic agriculture. Since 2016 their occurrence in books, news stories and on the internet has increased dramatically, which reflects the fact that they have now been adopted by a wide range of NGOs (e.g. The Nature Conservancy,

the World Wildlife Fund, GreenPeace, Friends of the Earth), multi-national companies (e.g. Danone, General Mills, Kellogg’s, Patagonia, the World Council for Sustainable Business Development) and charitable foundations (e.g. IKEA Foundation). In relation to this newfound popularity, Diana Martin, the Director of Communications of the Rodale Institute, cautioned ‘It’s [Regenerative Agriculture] the new buzzword. There is a danger of it getting greenwashed’.

The positive versus negative divide

A problem with using the distinction between regenerative farming and sustainable farming is an assumption that the former is producing positive ecosystem function outcomes while the latter is not. For example, the WA Landcare Network says on its website that “regenerative agriculture has been practiced successfully by a relatively small number of farmers across Australia for many years. These farmers have practiced a holistic approach to land management that keeps water in the landscape, improves soil health, stores carbon and increases biodiversity. This ecosystems approach has also proved to support increases in productivity over traditional agricultural methods.”

In other words the Network seems to have concluded that the vast majority of farmers in the state are degrading their landscapes but provide no evidence to show it. It also assumes that the “small number of farmers” have a stranglehold on ecosystem function knowledge and the majority of farmers are ignorant of this knowledge or have no interest in it.

For a landcare network to make this assumption is strange as its very existence via tax payer funding is based on encouraging farmers to improve natural resources on their farms. It is difficult to imagine that landcare groups have had no impact on improving ecosystem functions on farms since the program began at the national level in 1990.

In contrast, the National Landcare program has demonstrated that positive changes have been taking place for years. In its “Land management practice trends in Australia 2012” it shows a significant increase in adoption of no-till cropping across Australia, a practice with highest adoption in WA, figures 6A and 6B. No till cropping is responsible for significant improvements in soil health, soil water holding capacity, retention or slight increase in soil carbon, reduced greenhouse gas emissions, and higher crop yields particularly in low rainfall years. No-till is a fundamental practice advocated by RA practioners.

Figure 6A: No till cropping has been widely adopted by Australian farmers over the last 25 years. Source: Land management practice trends in Australia Building on success – National Landcare Program.

Figure 6B: No-till farming adoption increased significantly once appropriate herbicides and sowing machinery which could handle retained stubble were developed during the late 1980’s and in the 1990’s. WA farmers became the highest adopters because of the fragile nature of their sandy soils. Source: GRDC.

Figure 6C: No-till farming is increasingly being combined with precision sowing which ensures a wide range of ecosystem functions are protected and improving in paddocks involved in holistic agricultural science based farming. Here a legume break crop, lentils, has been sown between rows of cereal stubble from the previous year’s crop. Photo: Patrick Francis.

Other definitions of regenerative agriculture seem to reinforce a division between farming methods and in particular between the types of inputs used without recognising changes taking place over the last 30 years: “Regenerative Agriculture is a system of farming principles and practices that increases biodiversity, enriches soils, improves watersheds , and enhances ecosystem services. Regenerative Agriculture aims to capture carbon and aboveground biomass, reversing current global trends of atmospheric accumulations. At the same time, it offers increased yields, resilience to climate instability, and higher health and vitality for farming and ranching communities. The system draws from decades of scientific and applied research by the global communities of organic farming, agroecology, Holistic Management, and agroforestry’ Source: http://www.regenerativeagriculturedefinition.com/

This definition seems to be highlighting a difference between the science associated with organic farming and that of conventional farming which misrepresents what has been happening in scientific research and extension for many years when examined across its components such as soil chemistry, soil biology, plants and animal science and genetics, climate science, and engineering. All these factors combine to achieve the outcome depicted in Figure 6C which shows conventional cropping practice involving no-till, precision planting (2cm accuracy) and controlled traffic (all wheels follow on the same tracks in the paddock for each operation).

The Regen WA group of farmers makes a stark distinction between its members and the rest of the state’s farmers on its web site: “Within the agriculture industry, there was a need to support and encourage farmers who are willing to break away from conventional farming to trial practices that may prove to be more sustainable (profitable, socially, ethically and environmentally responsible). … RegenWA aims to support farmers to transition from current conventional practice to leading sustainability practices.”

The Western Australia Department of Primary Industries involvement with regenerative agriculture takes a more circumspect approach. It’s web site says “Regenerative landscape management is defined as: The application of techniques which seek to restore landscape function and deliver outcomes that include sustainable production, an improved natural resource base, healthy nutrient cycling, increased biodiversity and resilience to change.”

Success stories usually anecdotal

But it continues on to say: “Many of the successes claimed by regenerative farming advocates are anecdotal, with limited valid scientific reporting from Western Australian climate, soils and landscapes, to demonstrate the long-term economic or sustainable benefit. To drive practice change by agricultural producers, solid credible evidence is required on the impact and repeatability of regenerative agriculture practices on the physical, chemical and biological health of the soils and the associated long-term economic, environmental and social benefits. …The RegenWA program and its members have an important role to play in documenting the scientific evidence for these practices.”

Interestingly the WA Department of Primary Industries fails just like the WA Landcare Network to mention the many positive practice changes that have taken place across the state’s cropping and grazing areas over the last 30 years, for example adoption of no-till cropping, figure 6C.

Since 2015 in Australia the regenerative agriculture term began to be adopted by more organisations with a strong connection to what was usually termed holistic farming. Organisations like Soils for Life and consultancy firm RCS have become strong users. Even so both organisation were sponsors of a Holistic Farming Workshop held in Wandoan Queensland in November 2019. It seems as if both terms are interchangeable.

In 2017 Charles Massy turned the term regenerative agriculture into more common use when he published his book “The Call of the Reed Warbler” and drew an ideological line in the sand between what he interpreted as regenerative agriculture and conventional or industrial agriculture. According to Massy: “In its original derivation, the verb ‘regenerate’ also has moral and ethical connotations. So I would say that organic farming is one of a range of practices that comprise regenerative agriculture: from holistic/ecological grazing, to agroforestry, biological cropping, pasture- and No-kill cropping; and biodynamics and more.” (Source: https://www.echo.net.au/2018/08/charles-massy-interview/).

By giving regenerative agriculture moral and ethical connotations Massy created an unprecedented divide amongst farmers based on the methods they use. His views were widely circulated via the media providing him unequalled coverage. His message promoting regenerative agriculture as a distinct alternative to industrial agriculture is enormously appealing to city audiences, department bureaucrats and journalists who cannot distinguish between agriculture methodology fact and fiction, or scientific proof versus anecdotes.

As well, because Massy’s book contained case studies of innovative farmers who were known for their holistic methods, they too became willingly or unwillingly champions of, or participants in his interpretation of regenerative agriculture. And champions with an alternative approach often appeal to organisations such as catchment management authorities, landcare networks and local governments tasked with attracting landholders to improving farming practices with millions of dollars of federal government landcare funds.

Over time the RA brand and engagement of its high profile practioners has become the entrée to successful NRM funded farming and education projects. Agencies are virtually guaranteed funding when regenerative agriculture is mentioned in project proposals.

A February 2020 North Central (Victoria) Catchment Management Authority media release is a classic example: “Fifteen months in, the (CMA’s) Regenerative Agriculture project is enjoying strong interest with over 100 landholders participating in four groups across the North Central CMA region. The project offers grants to community groups in priority areas to increase the adoption of improved land management practices and technologies that protect against soil carbon decline, wind erosion, soil acidification, and vegetation and biodiversity loss. The aim is to regenerate and reinvigorate the productive and ecological health of the region’s soils. The four landholder groups …. are funded to run workshops and implement on-farm demonstrations of regenerative agricultural practices.”

The Federal Government has adopted the regenerative agriculture mantra and actively supports programs associated with organisations promoting it, the most notable being Soils for Life which was founded by former governor general Major General Michael Jeffery.

In a message to Soils for Life members in its October 2019 newsletter chairman Jeffery said “The Prime Minister recently announced the re-appointment of the National Soils Advocate.. .A team in the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet supports the Advocate.”

Profitability research

In 2018 the regenerative agriculture farming “method” became more entrenched as an alternative approach to conventional or agricultural science based farming when the National Environmental Science Program – Emerging Priorities (NESP – EP) released the report “Farm profitability & biodiversity – graziers with profitability, biodiversity and wellbeing” by Sue Ogilvy et al. The investigators compared the financial performance of 15 NSW grassy woodlands regenerative agriculture champion graziers with ABARES Farm Survey data of all farmers in the same districts.

This study is worrying because it elevates one group of 15 farmers with values and grazing management agenda aimed at maintaining or restoring the condition of box gum remnants to the criteria set out in the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Act (EPBC) to its pre 1750 ecological state, to a superior level to the management being practiced by other farmers who have different values less closely related to the Act.

These superior managers are described in the report as self-styled regenerative graziers who claim “…that they generate higher or more dependable profitability than other producers in their regions and that their grazing practices help to conserve valuable ecological functions of box gum grassy woodland communities.”

The danger of this report in the wider context of holistic grazing in farming areas that have undergone extensive change since white settlement is its elevation of a narrow set of criteria which outside the 15 farms involved may support healthy but different ecosystem functions and profitability. For instance one of the three key selection criteria for participants is “they had been applying a low or no input operations policy and using sensitive management of grazing.” In other words the farmers could not be using organic or inorganic fertiliser. In agricultural areas of Australia (above 400mm annual average rainfall) where livestock carrying capacities per hectare are moderate to high not replacing nutrient exported off farm via livestock, wool and milk is tantamount to mining the soil’s nutrients.

Chicken manure a threatening process

Ironically the data of one the 15 regenerative farmers went close to being removed from the analysis when it was discovered that in the final year of the report period he/she had applied chicken manure to native pastures. In the opinion of the report authors “This is a threatening process for grassy woodland and native pastures and will significantly inhibit the health and regeneration of these ecological communities for some time.”

There was originally a 16th regenerative farmer in the study who ran a mixed grazing and cropping business. But his/her financial results were excluded because the farm “… exceeded the threshold of 30% intensive use for the period of the study ….despite the grazed grassy woodlands being judged to be healthy. “

These last two examples highlight how the regenerative agriculture or regenerative farmer terms can be manipulated to suit particular individual champion or group agendas. As well, the terms can lose their holistic meaning as in this example where management is focused on a narrow agenda defined by the pre 1750 ecosystem.

“The study found that the regenerative graziers that contributed to this project are often more profitable than comparable contributors to the ABARES Farm Survey, especially in dry years, that the levels of farm profit were similar to published industry benchmarks of ‘elite’ producers and they experience significantly higher than average wellbeing when compared to other NSW farmers.”

Despite its narrow focus this study gave regenerative agriculture a profile and status boost that may have enhanced its importance amongst government and semi-government bureaucrats tasked with environmental protection and enhancement across their jurisdictions. An important fact made known by the report authors received no attention: “The sample of graziers was small and the lack of data about the ecological characteristics of the broader population of graziers in the grassy woodlands biome means that it is not possible to confirm any causality between the condition of the ecosystem and profitability or with higher wellbeing.”

Profitability of RA methods is often contested by farm consultants who promote an agricultural science and productivity per hectare based approach to farming. The evidence from farming practice suggests most professional farmers operate in between the two extreme approaches, they understand the holistic connections between supporting ecosystem functions and maintaining long-term profitability and embrace them to different extents depending on a wide variety of factors and influences.

The most recent farm profitability review of RA titled “Regenerative Agriculture – Quantifying the cost” was undertaken by John Francis (no relation), Director, Holmes Sackett a southern NSW farm consultancy business. It contested the claims in the “Farm profitability & biodiversity – graziers with profitability, biodiversity and wellbeing” review by Sue Ogilvy et al that the RA farmers involved “…generate higher or more dependable profitability than other producers in their regions.”

“The analysis shows that, over the decade 2007 to 2016, farms in the Holmes Sackett benchmarking data set with ten consecutive years of data, who managed systems not classified as regenerative agricultural systems, generated operating returns or returns on assets managed (ROAM) of 4.22 percent. This compares with the group of producers practicing regenerative agriculture who returned only 1.66 percent. The average cost per farm, over the decade studied, of regenerative agriculture when compared to farms employing systems that are not classified as regenerative agriculture, equates to $2.46 million,” Francis writes.

Francis concluded that these results mean at least on a financial basis regen ag farmers are somewhat irresponsible at the agricultural industry level.

“The consequences of a landscape that is far less resource efficient cannot be ignored. The consequence of regenerative agriculture …. go well beyond the $2.46 million cost of production foregone (for claimed well-being and ecological benefits over 10 years) and the financial inefficiency. Lower intensity landscapes mean less livestock, lower inputs, lower returns and less farm investment – these are features that have potential implications for rural and regional Australian communities beyond the farm gate. “

Francis’s “lower intensity landscape” conclusion is just as divisive as Massy’s “moral and ethical connotations” argument for practicing regenerative agriculture, as personal attitudes are based on values which should not be judged.

Farm profitability comparisons can be poor instruments for comparing financial performance even within a like minded group. That’s because they often fail the holistic test for financial decision making. It is well known that each farmer’s financial imperative for profitability varies for a range of reasons such as:

* Equity – for example a farmer with 100% equity compared to one with 80% and a $2 million bank loan to pay off.

* Succession status – having a commitment to supporting the farmer’s own family as well as paying out parents and siblings.

* Age – older farmers, with few if any family commitments such as school fees.

* Off-farm investments. Some farmers have 20 – 40% of total gross income generated off farm.

* Professional status – many small to mid-sized farms are owned by people who are professionals in well paid careers other than farming. ABARES data shows that around 45% of Australian businesses described as ‘farms’ generate less than $100,000 gross income per year. So off-farm income is more important to many of these owners than on-farm income.

Often the case studies highlighting RA successes reported on web sites seem to be based on farms owned and managed by professionals with other careers.

Unsurprisingly, when read closely the Holmes Sackett analysis of regenerative and conventional ag contains practices which are common to both methods. The conventional ag farmers use organic and inorganic fertilisers, they apply lime for soil pH amelioration, they use livestock containment paddocks to ensure sufficient plant cover is retained to protect soil and improve rainfall infiltration. There are far more practices which are common in conventional farming and regenerative agriculture than there are practices which are different.

Conclusion

Regenerative agriculture has emerged over the last five years under the misapprehension of providing a more holistic methodology for profitable farming while improving ecosystem functions compared to conventional or agricultural science based farming. Its most prominent farmer champions and supporting organisations are creating a divide between the farmers who base their management around agricultural science and the farmers who contend that such management is flawed. In practice both groups of farmers share many common practices which are constantly changing as a result of new scientific, technological and ecosystem function knowledge, while dealing with an increasingly variable climate and volatile national and world markets for food and fibres.

Unfortunately this divide between RA farmers and conventional farmers has the potential to widen because consumer preferences are nourished by farmers and businesses exploiting differences. The RA brand provides potential for differentiating food and fibres based on farming methodology, especially those that are in stark contrast to mainstream methods. The issue for potential farmer adopters and food consumers is deciding on which version of regenerative agriculture is most believable and beneficial for their personal objectives and whether or not the version has a scientific or ideological foundation.

Next article: Regenerative agriculture’s version of science creates division between farmers.

References:

Gabrielle Wong-Parodi, Irina Feygina. Understanding and countering the motivated roots of climate change denial. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 2020; DOI: 10.1016/j.cosust.2019.11.008

John Francis, Holmes Sackett, Regenerative agriculture – quantifying the cost, at https://www.holmessackett.com.au/publications-and-tools

Ogilvy, S., Gardner, M., Mallawaarachichi, T., Schirmer, J., Brown, K., Heagney, E. (2018) NESP-EP: Farm profitability and biodiversity project final report. Canberra Australia

Savory Global: https://savory.global/land-to-market/eov/

“Regenerative Agriculture: An agronomic perspective”, Ken Giller et al, Outlook on Agriculture February 2021.

Pat

excellent

David Everist

Hello Patrick,

I found this post very interesting in terms of regenerative agriculture from an Australian perspective.

I administer a website dedicated to small family farms/homesteads practising sustainable agriculture and have reposted it here: https://rainwaterrunoff.com/what-makes-a-regenerative-agriculture-farmer-in-australia/

Thank you Pat Francis for your thorough investigative journalism. It is a pleasure to read such well informed commentary.

Well researched article, shame the concentration was on a “divide”. Practitioners are always looking for a better way, some have come to believe they have been degrading their land with synthetic chemicals and some don’t – there is no need to be divisive about it.

The inference that agricultural science and regenerative agriculture are different things is incorrect – it’s the way a farmer applies the Chemistry that is different.

Good observation !

Good to see a balanced discussion on this topic .