Mulesing under pressure from Merino wool value chain players

By Patrick Francis

If Australian wool farmers and their national wool research, marketing and development organisation Australian Wool Innovations don’t take action on removing mulesing as an industry accepted practice, market outlets for mulesed sheep wool, even if pain relief is used, are likely to shrink. Some Merino wool processors, designers and clothing retailers will bypass Australian wool, preferring to source it from New Zealand, South Africa and Argentina where the issues of mulesing, ceased mulesing and pain relief at mulesing do not exist because procedure is not practised.

The message to Australian Merino farmers to act is becoming increasingly apparent. The marketability of wool from mulesed sheep where the operation is undertaken without pain relief is declining and the same may not be far off for Merino wool from sheep mulesed with pain relief. Mulesing is giving Merino wool such a bad reputation that some in the value chain contend that wool’s future as an elite textile will come under increasing threat. It may not be long before wool from mulesed sheep is only marketable in the commodity textile trade where the value chain has little or no interest in transparency and accountability for animal welfare and environmental management.

The CEO of South African wool industry’s representative organisation, Cape Wools, Louis De Beer recently told Fairfax Media that the Australian wool industry’s failure to cease mulesing is threatening the viability of the world Merino industry.

“Consumers are telling us that they are concerned with the (mulesing) procedure (although not undertaken by South African Merino farmers) which means we have to be concerned about it and find a collective solution – there is no point in being arrogant about it. We have to be sympathetic to the consumers concerns and we have to understand that cash is king and they are buying our product,” De Beer said.

He also said that while wool processors and textile manufacturers can source non mulesed wool from South Africa, South America and New Zealand, consumers could not often differentiate the source of Merino and subsequently linked all Merino to Australian wool where most Merino sheep are mulesed. This was the reason some designers, retailers and consumers were turning their back on Merino textiles irrespective of its country of origin.

A similar message to Louise De Beer has been delivered to Merino wool farmers by the president of the Australian Council of Wool Exporters and Processors, Chris Kelly. He recently called for mandatory use of the National Wool Declaration so buyers know the mulesing status of all wool offered for sale. He told Fairfax Media that mandatory declarations would provide more choice in the auctions for retailers and suppliers wanting welfare friendly wool.

“The impact (of mulesing) to the Australian Industry is we cannot compete with the countries (whose sheep) are non-mulesed. Previously if we had an inquiry for (non-mulesed) Australian wool, we have had to say they are not available because of a lack of declared supply, and the order is dragged from Australia. We are receiving more inquiry for non-mulesed status wool which is flowing into real business, not just idle threatening talk.

“It is not just the Europeans or Japanese, now it is coming, albeit very slowly, from the Chinese market,” Kelly said.

Given the reputation of Australian Merino wool is suffering it is difficult to comprehend why Australian Wool Innovations is so opposed to an Australian industry where mulesing is no longer practiced. Similarly, Animal Health Australia’s new “Model Code of Practice for the Welfare of Animals – sheep” which allows mulesing lambs without pain relief, demonstrates the level of contempt these industry organisations have for processors, designers, retailers and consumers that don’t want to be associated with wool from mulesed sheep.

What is so frustrating for many informed players in the Merino wool value chain is that they know mulesing is not necessary to prevent fly strike because there are a significant number of farmers in Australia who don’t undertake the procedure and whose flocks have minimal body or breech fly strike incidents. The pro-mulesing advocates continually refer to the need for mules based on the traditional belief that it prevents suffering and death due to breech flystrike. But in saying that, they conveniently ignore the issue of flystrike mortality due to body strike which is not prevented by mulesing but can be by genetic selection and management just as breech strike can be prevented without mulesing.

The stand out farmers demonstrating this to processors, designers and consumers are the SRS Merino breeders whose genetic selection programs have infused their sheep with resistance to body and breech fly strike. This group of farmers has a stated position about not mulesing:

“In 2001, SRS Merino stud breeders took the unanimous decision to stop mulesing as their Merino sheep were plain bodied and naturally resistant to fly strike. Most of the forty SRS studs had stopped mulesing by 2004 and all by 2008. It is a simple and easy process to implement and takes no longer than 3 to 5 years to achieve. The other benefits that have flowed to their flocks are more lambs, better lamb survival, good fleece weights of high quality wools, much easier shearing and better processing wools. Given that the genetic solution to mulesing is already in place, and has been for 12 years, the group is surprised and disappointed to see that only 7 % of the Merino wool sold in Australia is declared as being produced by Merino sheep that are free of mulesing.”

The SRS breeders and other Australian Merino farmers who don’t mules their sheep can participate in specific quality assurance programs where mulesing is not allowed. These include all the certified organic wool programs, and EthEco and New Merino accredited flocks.

Wool declarations

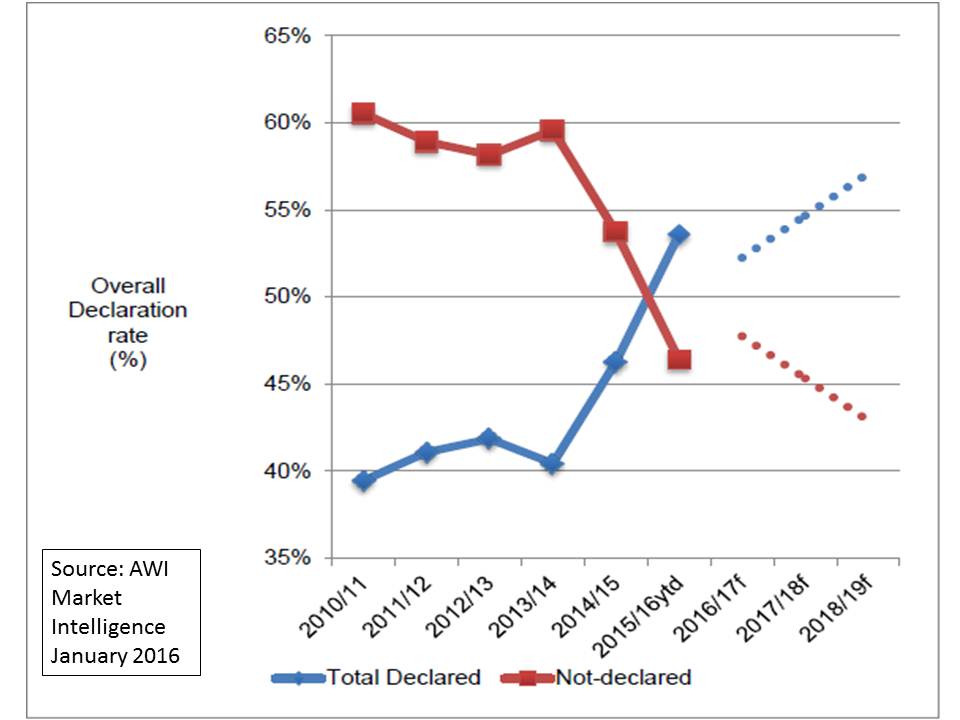

The state of play as of January 2016 according to the Australian Wool Innovations Market Intelligence Report is that 54% of all Australian wool lots are declared as either non-mulesed, ceased mulesing, pain relief at mulesing or mulesed. This means 46% of wool lots have no declaration about mulesing status which most likely means the wool is from sheep who as lambs were mulesed without pain relief, figure 1.

Figure 1: More Australian sheep farmers are submitting the National Wool Declaration for their sale lots.

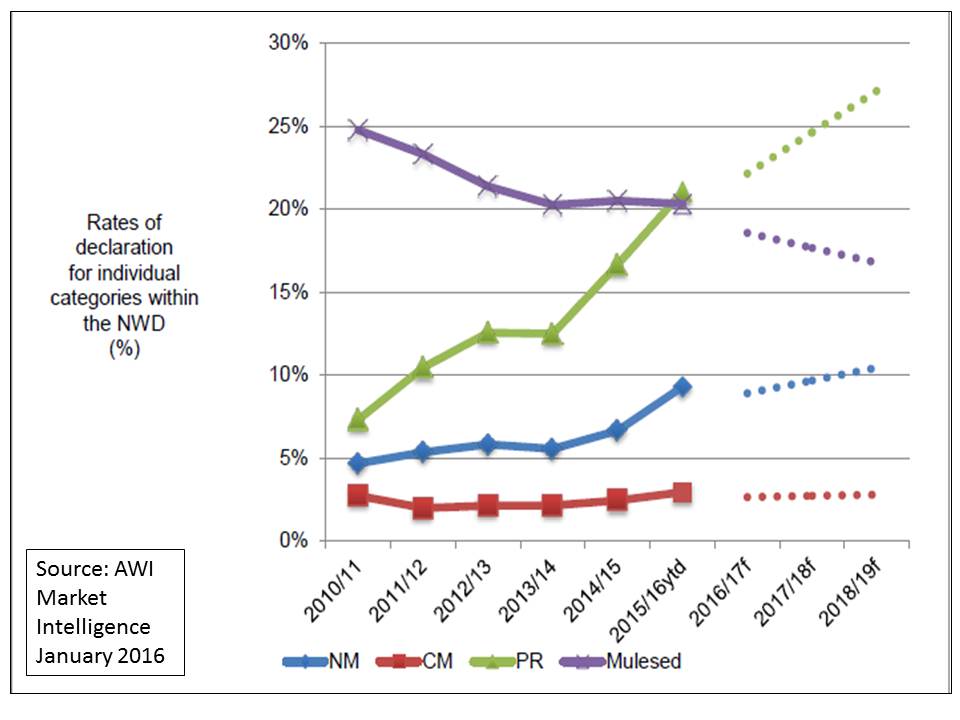

The strongest growth category for the National Wool Declaration is pain relief at mulesing which has jumped from 12% to 20% of declarations in the last two years. The non-mulesed category has also increased but at a slower rate, rising from 6% to 9% of declarations, figure 2. The combined proportion of the declared clip which is non-mulesed or ceased mulesing is approximately 12%.

Figure 2: The largest growth in National Wool Declarations from 2013/14 to 2015/16 has been for mulesed with pain relief wool.

The data from figures 1 and 2 shows 46% of clips are undeclared which generally means mulesed without pain relief and 20% of the clip is declared mulesed without pain relief. Add in mulesed with pain relief at 21%, then as at January 2016 87% of the Australian clip is harvested from sheep mulesed as lambs mostly without pain relief.

This means wool buyers have little scope to source the Australian wool types they need to blend together to meet orders from the non-mulesed/ceased mulesing pool. This data substantiates the concerns of Louis De Beer and Chris Kelly.

On the world export markets 2011 production data (AWI) indicates there is around 60,000 tonnes (clean) of non-mulesed Merino wool (less than 24.5 micron) available mostly from South Africa, Argentina and New Zealand and around 190,000 tonnes (clean) of mulesed wool from Australia. Non-mulesed and ceased mulesed wool from Australia contributes about 7000 tonnes (clean) to the world total for 2011.

Figure 3: Some wool clothing retailers prefer to purchase Merino wool from countries other than Australia, so mulesing is not a “turn-off” for consumers.

No mulesing in Responsible Wool Standard

The latest certification program available to Australian Merino farmers to join which prohibits mulesing and accommodates wool from ceased mulesing flocks is the Responsible Wool Standard (RWS) developed by the US headquartered but global non-profit organisation, Textile Exchange.

The Responsible Wool Standard has created significant media attention because of its stand on mulesing and was roundly criticized by the CEO of Australian Wool Innovations because of this.

The Textile Exchange has staff located in eight countries and its members (while not listed on its web site) are companies involved throughout the textile chain. How influential this business is or will be for Merino wool quality assurance is difficult to ascertain. From its annual report its work to date has been within the cotton value chain with an emphasis on organic cotton. In 2015 it had an annual income of US$1.6 million and expenditure of US$1.7 million. Certification fees are it major source of income so promoting farmer adoption of the Responsible Wool Standard will be a major objective in 2016.

Its mission statement is to “…inspire and equip people to accelerate sustainable practices in the textile value chain. We focus on minimising the harmful impacts of the global textile industry and maximizing its positive effects.”

The draft RWS is in effect an on-farm certification program covering sheep husbandry, sheep welfare and farm environmental management. The standards stipulate what can and can’t be done on participants farms and how and when to do it. They are not unlike standards for organic certification.

The thinking behind the RWS is evident from the Textile Exchange statement: “Wool owes its unique properties to the sheep that grow it, and we owe it to the sheep to ensure that their welfare is being protected. To this end, Textile Exchange is developing the Responsible Wool Standard.”

The Exchange says the RWS is being developed through a multi-stakeholder working group which anyone can provide input to via its web site.

“The International Working Group represents the broad spectrum of interested parties, including animal welfare groups, brands, farmers, wool suppliers, supply industry associations, covering both apparel and home categories.”

Australian Wool Innovations is not a part of the International Working Group and the International Wool Textile Organisation acted as an observer.

The goals of the Responsible Wool Standard are to provide the industry with the best possible tool to:

- Recognize the best practices of farmers around the globe

- Create an industry benchmark for animal care and land management to drive improvement where needed

- Ensure that wool comes from farms with a progressive approach to managing their land, and from sheep that have been treated responsibly

- Provide a robust chain of custody system from farm to final product so that consumers are confident that the wool in the products they choose is truly RWS

In an interview in the electronic news bulletin Sheep Central, Australian Wool Innovations CEO Stuart McCullough unleased an extraordinary attack on the Responsible Wool Standard.

McCullough’s statements are not what is expected from the head of an organisation supposed to represent the best interests of all its levy payers as suggested by its mission statement: “AWI’s mission is to invest in research, development, marketing and promotion to: enhance the profitability, international competitiveness and sustainability of the Australian wool industry; and increase demand and market access for Australian wool.”

They demonstrate an organisation out of touch with the certification programs which wool levy payers may wish to participate in. If he took the time to read the Textile Exchange’s Responsible Wool Standard he would know that it is a voluntary program that wool growers and other players in the value chain may agree to participate in.

The interview didn’t present any evidence as to why the Responsible Wool Standard should be considered a threat to Australian Merino wool farmers given the CEO has “…never seen their Responsible Wool Standard”. To say AWI “…will not engage with these people (Textile Exchange)…and we will not listen to them” is arrogant in the extreme as it is highly likely some Australian Merino sheep farmers will participate in it.

To suggest the Textile Exchange wants to “…to impose disciplines on our wool growers…” is inaccurate as it is a program, just like all the others, which farmers and processors voluntarily participate in.

McCullough’s attitude suggests AWI is only interested in engaging with Merino sheep farmers and value chain participants who hold the same views about mulesing practices as it does. He scorns the Textile Exchange’s approach to sheep welfare on the basis that the organisation “…is based in North America, at the top of the world..”. But where is most of Australia’s high value Merino textile clothing sold?

In making these comments about the Responsible Wool Standard McCullough is ostracising levy paying Merino sheep farmers who aspire to different ideals by personal choice and/or by participating in programs with specific animal welfare standards involving not mulesing their sheep. He also highlights to the Merino wool value chain and consumers that AWI prefers to support the sheep welfare views of Australian Merino wool farmers who practice traditional husbandry techniques (figures 1 and 2) and are not inclined to embrace sheep genetic selection and management strategies to avoid the need for mulesing to prevent breech fly strike. That’s a curious position for AWI because over the last decade it has spent millions of dollars of levy payers funds on research programs to uncover alternatives to mulesing.

Genetic selection tools available

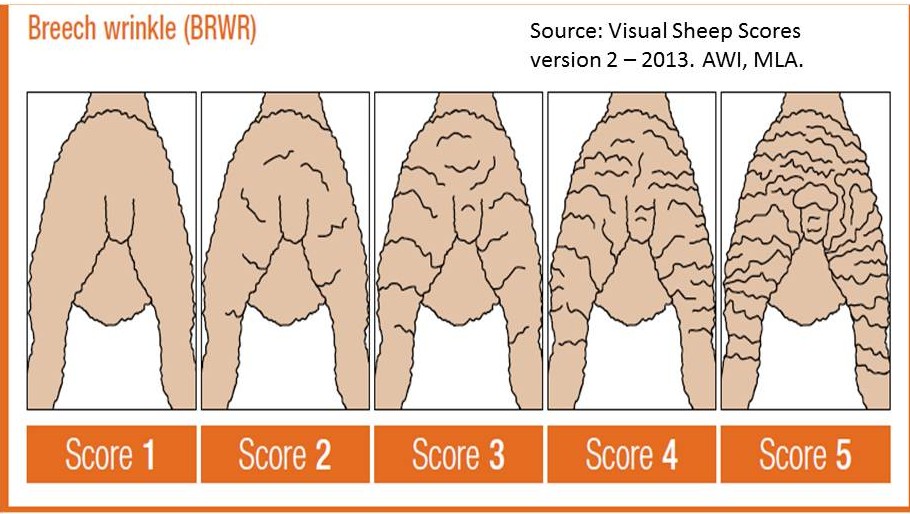

As well Australian Wool Innovations in conjunction with Meat & Livestock Australia have developed a visual Merino sheep trait scoring system which “enables sheep breeders and classers to record and submit visual score data and genetic information to Sheep Genetics to progress development of across flock Australian Sheep Breeding Values for visually assessed traits”. When used across wool quality, conformation and breech traits, Merino sheep farmers can select sheep which are genetically resistant to fly strike without the need for mulesing.

Figure 4A: Breech wrinkle scoring of lambs and hoggets is one of a combination of genetic traits that Merino sheep farmers can select for to remove the need to mules their sheep to prevent breech flystrike; it also helps prevent body flystrike.

Figure 4B: When farmers such as the SRS Group breeders select for skin and wool traits such as plain bodies without wrinkles (left) they eliminate the need to mules their sheep altogether .

The results shown in Figure 4 B are repeated in the AWI supported Flyboss web site which provides farmers with an information resource around strategies to avoid sheep body and breech fly strike. In the “Breeding and selection” section it outlines how breech wrinkle scoring and selection can minimise fly strike. It says there are three major factors contributing to the risk of breech strike and “to reduce these three risk factors the primary selection trait is breech wrinkle.”

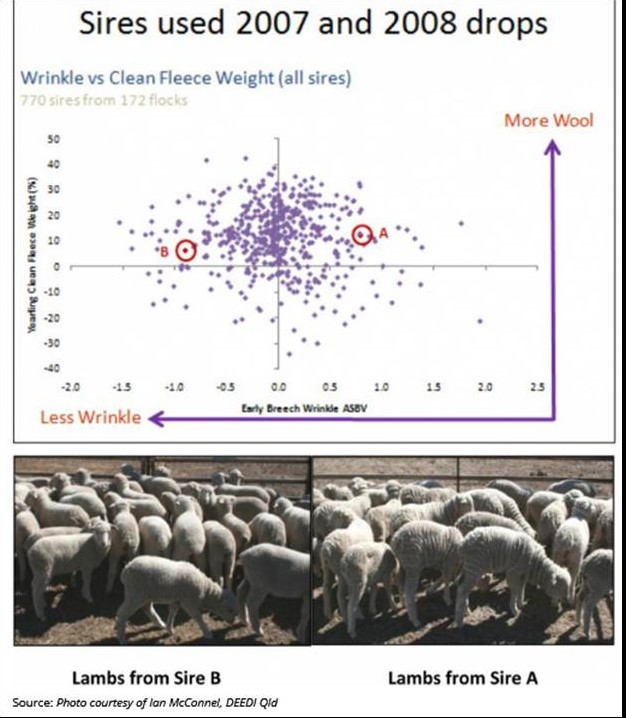

The web site demonstrates that farmers who combine balanced trait selection including breech wrinkle and across flock selection with rams having breech wrinkle ASBVs can make quick improvement in flock wrinkle score and maintain clean fleece weight. It provides the example of two groups of lambs which were born from a mob of ewes of the same genetics, but joined to different sires at a Central Test Sire Evaluation site, figure 5.

Figure 5: How selecting sires for early breech wrinkle sheep breeding value can influence breech wrinkle in their progeny. Source: Flyboss Breech wrinkle scoring and selection.

The lambs on the right were sired by Sire A with a higher wrinkle breeding value (more wrinkle). The lambs on the left were sired by the Sire B with a lower wrinkle breeding value (less wrinkle) and a similar breeding value for clean fleece weight.

“The visual differences in terms of body wrinkle are clear. Based on breeding values both groups of lambs could be expected to have similar fleece weights as adults,” the web site says.

Despite so clearly demonstrating that breech wrinkle can be eliminated by genetic selection and therefore reduce likelihood of flystrike without mulesing the Flyboss web site’s “flystrike decision support tools” ignores the impact plain breech sheep has on flystrike. The tool allows farmers to evaluate their flocks fly strike risk by entering various options about shearing date, first crutching date, second crutching date, first chemical treatment, second chemical treatment and finally breech modification. But the options under breech modification are “none, mulesed, clips, intradermal”. The “none” option gives no differentiation between high and low breech wrinkle score flocks. So with this tool “none” always gives worse breech and body strike outcomes than “mulesed” irrespective of husbandry options used.

It is extraordinary the option of “plain breech” (wrinkle scores 1 and 2 versus wrinkle scores 3,4 and 5) is not available within breech modification as its impact on reducing flystrike, especially in conjunction with timely husbandry associated with crutching and shearing is significant. It’s omission seems to suggest that the people or organisations behind the Flyboss web site don’t want farmers to understand the impact the plain breech trait (wrinkle scores 1 and 2 in figure 4A) has on fly strike.

The data is clear, all Merino farmers have the genetic selection tools at their disposal to avoid the need for mulesing. Added to that Merino sheep farmers have a range of management tools to also prevent fly strike including application of pesticides (jetting and dipping) and wool removal (crutching or shearing) prior to the most threatening fly strike periods. As well, a precursor for breech strike, scouring due to internal worm infestation can be minimised and prevented using anthelmintics (drenches) in conjunction with holistic grazing management and selection for genetic resistance to worm larvae burdens.

So despite Merino farmers having a host of defences to prevent breech and body strike, the industry’s peak research and marketing organisation Australian Wool Innovations and its peak animal welfare organisation Animal Health Australia continue to advocate mulesing as acceptable practice.

Woolen mill owners support mulesing with pain relief

Despite the fact that Merino farmers have a range of tools available to them to avoid the need for mulesing, European wool processors have called on Australian farmers to adopt pain relief with all mulesing rather than stop mulesing.

Prior to the International Wool Secretariat’s March 2016 annual conference in Sydney 34 international woolen mill owners called for the Australian sheep industry to make pain relief a mandatory component of on-farm sheep surgery which includes mulesing. The petition has been distributed by European wool-buyer and processor Laurence Modiano, director of G Modiano Ltd.

The petition is in response to Animal Health Australia’s “Australian Animal Welfare Standards and Guidelines for Sheep” which allow mulesing two day old to six month old lambs without pain relief.

The petition signatories include Biella of Italy, Dawson in the UK, Chargeurs Wool in France, the Italian Wool Trade Association, plus wool processors of India, Japan and China.

Modiano said the Animal Health Australia’s “Animal Welfare Standards and Guidelines for Sheep” involving mulesing are a retrograde step which, if adopted by farmers, could contribute to the destruction of the wool industry altogether.

“If these (mill owners) requests are ignored and wool is increasingly associated with pain and cruelty, more and more brands will make the reluctant decision to remove it from their collection.”

Figure 5: Animal Health Australia’s latest draft guidelines for sheep welfare allow farmers to mules sheep from two days to six months of age without pain relief, despite suggesting options for breech strike prevention that “should be considered” such as such as genetic selection, management and when practiced it “should be accompanied by pain relief”.

In saying this Modiano is also opposed to the Responsible Wool Standard which outlaws mulesing altogether. He contends if RWS certification is demanded by a significant number of wool buyers and retailers the price of non mulesed and ceased mulesed Australian wool will soar to a point when it becomes too expensive for mass market retailers, so they stop buying Merino wool or at least Australian Merino.

At the same time wool from mulesed and mulesed with pain relief he contends becomes heavily discounted.

“I see a situation where many growers simply leave wool altogether, with implications for all those who depend on the fibre. Please trust me, the writing is on the wall,” Modiano said.

Modiano’s position surrounding compulsory pain relief and AWEX declaration seems at odds with a statement from his Australian company managing director Stuart Clayton. He told ABC Rural: “From our company’s point of view it’s a very big issue in Europe. Spinners and weavers who we sell wool tops to, are largely requesting that it be from ethically treated sheep, you know non-mulesed. We’re finding we’re losing sales.”

Clayton is saying mulesing with pain relief is not sufficient and that wool from non-mulesed sheep is increasingly demanded.

He said the market would now pay almost a 10 per cent premium for non-mulesed wool from Australia.

“Spinners and weavers are getting those requests from the companies that sell to the bigger brands, it’s all the way down the chain. At some point it has to get down to growers and say this is what the industry needs.”

SustainaWOOL™

Italian wool processor Reda and Vitale Barberis Canonico operate in Australia buying wool direct and at auction through their jointly owned New England Wool. These two traditional Italian style wool processors have three programs in place to source wool of particular style which also carries sheep welfare and on-farm environmental credentials.

While the programs accommodate an entrenched attitude amongst some Merino farmers to mules sheep they are providing some incentive to move away from the practice. These two Italian companies approach is to provide a framework for change involving Merino wool demand chain knowledge, education and financial incentives. The three initiatives are:

- SustainaWOOL™ Integrity Scheme quality assurance accreditation. This involves meeting particular wool style characteristics, animal welfare standards and environmental standards. The animal welfare standards associated with mulesing require AWEX declaration of either pain relief (PR), ceased mulesing (CM), or non-mulesing (NM). All bales sold in the program are catalogue prefixed according their mulesing status. Random audits are undertaken to ensure the programs requirements are being met. According to New England Wool there are approximately 400 SustainaWOOL™ accredited properties in Australia which produced around 22,500 bales in 2015. The company says wool buying clients are increasingly looking at putting together lines of NM wool and demand is growing for this category.

New England Wool offers contracts to SustainaWOOL™ accredited farmers twice a year. The farmers can pledge a set number of bales of particular wool types (and with fibre diameter equal to less than 19 microns) which if acceptable is paid a premium of $2 – $4/kg clean above the prevailing market price. If the pledged wool is not of suitable type at that time, it is transferred to the auction market.

- Vitale Barberis Canonico’s Wool Excellence Club (WEC). This is an exclusive club for SustainaWOOL™ accredited Saxon Merino sheep breeders. The four pillars on which this exclusive “club” is based are: fibre quality, member training, member loyalty and farm sustainability. For wool that meets the company’s style requirements there is a 25% – 30% per kilogram clean premium above the current market price. While PR wool is accepted there is increasing interest in NM wool for this elite fibre.

- Reda Future Project. Another exclusive club for SustainaWOOL™ accredited Saxon Merino sheep breeders, but the acceptable wool types are wider than WEC. This enables members to pledge a higher proportion of their annual clips (possibly 80%) with a greater likelihood of bales being acceptable and earning the 30% premium. As its name suggests the Radar Future Project targets fine wool growing businesses which have a succession plan in place so the next generation of owner will also be suppliers.

Given the size of the premiums being paid to Merino sheep breeders in these three programs and the consumer markets these elite wools are destined for it is highly likely the buyers will look more favourably on NM Merino wool. How long it will be before NM becomes compulsory was not indicated by the companies.

Figure 6: SustainaWOOL™ is an Italian wool processor company owned audited program which demands a least pain relief at mulesing to be eligible to participate.

Australian Country Spinners no mulesing

Opting out of any controversy over mulesing is behind the decision by one of Australia’s few remaining wool processors, Australian Country Spinners, Wangaratta Victoria, to only source Merino wool from farmers who declare no mulesing on their National Wool Declaration.

Australian Country Spinners chief executive Brenda McGahan launched its new range of superfine wool at the United States prestigious craft fair, Vogue Knitting in New York. She told ABC Rural that in launching a new push into the US, the question of animal welfare should not be an obstacle.

“That’s a very important pathway for us, because knowledgeable knitters are very concerned about provenance, but they’re also concerned about animal welfare and it meant we could sidestep that whole issue.”

McGahan said knitters asked about mulesing, but by being able to say “‘the wool is non-mulesed’ the questions go straight to ‘how many colours? where do I get it?'”

“It means you’re having a conversation about the product and not side-tracked by other things. The way we explained it was; the very finest wool takes the finest care and it’s a huge investment from the woolgrowers to do this, and that’s why the wool of that quality commands a premium.”

Box story;

Responsible Wool Standards involve too much red tape

Review by Patrick Francis

The Responsible Wool Standards cover the following areas of sheep ownership and are all audited:

- Management

- Nutrition

- Infrastructure

- Health

- Behaviour

- Soil management

- Biodiversity

- Fertiliser management

- Pesticide use

After reviewing the Responsible Wool Standards I drew the following conclusions:

- Management module – all reasonable requirements for an audited program

- Nutrition module – reasonable requirements apart from 80% of animals having a condition score between 3 and 4.

- Infrastructure module – more orientated to farming environments where housing is required for part of the year. Does not include tall pastures (associated with herbage mass greater than 2000 kg dry matter per hectare) as a component of shelter.

- The health module has too much red tape in terms of management plans and routine health inspections. There was no mention of undertaking faecal egg counts before drenching or doing drench effectiveness testing. Other components are reasonable practice.

- Behaviour and handling module – all reasonable requirements.

- Soil management – has some good general guides but fails to include monitoring which demonstrates paddock stocking rate matches paddock carrying capacity. No mention of critical soil cover benchmarks such as 70% crown cover, 30% plant residue cover. No mention of grazing methods which prevent stock camps issues. Recommended annual soil testing of paddocks is excessive.

- Biodiversity module – mostly reasonable except for ban on exclusion fencing which is important for kangaroo control (as well as predators). Possible problem with prohibition on deforestation if legal for regrowth control.

- Fertiliser module – all reasonable requirements.

- Pesticide use module – all reasonable requirements.

To justify the considerable extra time and labour needed for paddock and flock monitoring and recording involved in this certification program, participating Merino sheep farmers must expect a premium price for their wool.