Media confusing climate change belief with successfully managing climate variability

By Patrick Francis

Coinciding with the COP 21 Climate Change conference in Paris has been an increase in the number of ABC Rural and News stories about farmers attitude to the issue. The coverage in most cases seems to confuse the connectivity between ecologically based farming, climate variability, drought management and business profitability. Stories are usually poorly researched with no attempts (as yet) to quantify key environmental indicator trends for Australian food and fibre production over the past 20 years and different farm sectors profitability.

One of the problem misunderstandings among most journalists is the generic reference to “farmers” as if they were some sort of homogeneous group running identical businesses. Nothing is further from the truth, with the different industries involving a wide range of professional skills, business types – full-time to lifestyle, and operating in widely differing environments and soil types. It’s time ag journalists stopped generalizing and addressed specific farming sectors and environments in which they operate. Greater understanding of developments would come from literature research to find out the degree of management practice change that has taken place over the past 20 years to accommodate climate variability, commodity price variability or stagnation and to improve farm ecosystem services such as healthier soils and increased on-farm biodiversity.

The ability of professional farmers to produce more grain, more livestock, and fruit and vegetables with less water, in higher temperatures, with more frosts and more variable rainfall while improving on-farm ecosystem function is a success story. Agricultural scientists as researchers, extension officers and advisors have supported interested conventional and organic farmers in achieving these outcomes over decades. The reality is that most professional farmers change management to meet the demands of their time. Those that don’t usually end up either working off-farm to support the business or sell up.

Benchmarking data across industries show impressive results in terms of meeting the challenge of climate variability with grain yields per mm of rainfall and livestock production per hectare per 100mm of rainfall increasing at a steady rate since the 1990’s. At the same time the Australian Bureau of Statistics has landcare participation data showing important on-farm environmental trends improving.

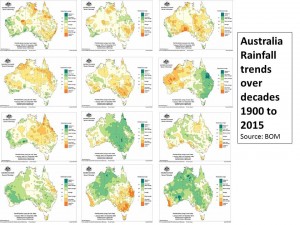

There is nothing new with coping with a variable climate in Australia as the Bureau of Meteorology’s “Australia’s Variable Rainfall” chart shows, figure 1.

Figure 1A: Highly variable rainfall is a feature of Australia’s climate which farmers are variously equipped to deal with.

Figure 1 B: Apart from variability Australia rainfall tends to have sequences of dryer and wetter than average years. Source: BOM.

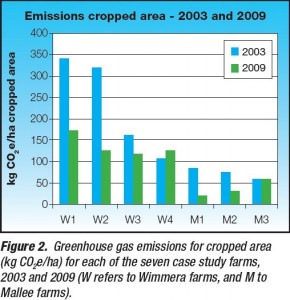

Despite this many of the ABC Rural journalists give the impression that managing climate variability is a recent phenomenon associated with outcomes predicted by climate scientists. Furthermore they make the assumption that farmers who are unconvinced that climate change is happening manage in a way that makes their business more susceptible to its outcomes or are less concerned about their farm’s greenhouse gas emissions. This is not necessarily correct as many farmers manage for crop and livestock productivity efficiency and in doing so reduce emissions, figure 2.

Figure 2: Many farmers are lowering their per hectare greenhouse gas emissions by adopting innovations for a host of agronomic, economic and efficiency reasons.

The key issues for farmers who run inter-generational profitable businesses in a variable climate are sufficient understanding of their management impact on ecosystem functions and productivity to ensure they are improving, having astute financial and marketing management skills (or employing them), and embracing timely succession planning. Whether or not farmers embracing these issues believe in anthropogenic climate change has not to my knowledge been proven.

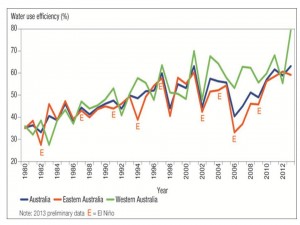

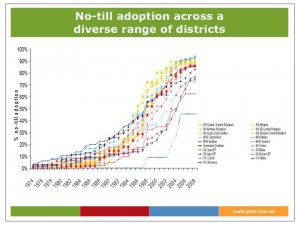

A good example of how changing farming practice is having positive impacts on business profitability as well as greenhouse gas emissions was recently demonstrated in a review of crop water use efficiency between 1980 and 2012, figure 3. It is not surprising that crop water use efficiency has increased the most in Western Australia where the adoption of conservation farming techniques is highest, figure 4.

Figure 3: Crop water use efficiency trend has been constantly increasing since 1980. Adoption of conservation farming techniques is improving soil health and subsequently its water holding capacity. Source: David Stephens May 2015.

Figure 4: Adoption of conservation farming has been fastest among Western Australia broadacre croppers. Source: GRDC.

A classic example of managing for maintaining ecosystem function in a variable climate is provided by Marie and Bob Purvis, Woodgreen station, north of Alice Springs. Theirs is a case study in the book “Nature and Farming” by David Norton and Nick Reid (CSIRO Publishing 2013). The Purvis’s have developed their management system “that is a model of sustainable rangeland management” over 52 years. Features of their system include:

- Subdivision and spelling of country

- A stocking rate that is sustainable through all seasons that initially improves and then maintains pastures and groundcover through boom and bust.

- A strategy of reducing cattle numbers to match the carrying capacity of the land and keeping a large proportion of the station in reserve.

- Ensuring that the stocking rate is geared to the survival of the palatable native species.

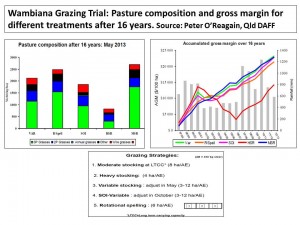

The Purvis’s approach is not new among innovative graziers and its implications for managing ecosystem function in a variable climate has been documented in long-term trials like the Wambiana Grazing Trail in North Queensland (near Charters Towers), figure 5.

Figure 5: Wambiana Grazing Trial trends for grazing treatments and gross margins. Source: Peter O’Reagain Qld DAFF.

In stark contrast the ABC Rural report “Farmer attitudes to climate change across generations” demonstrates the simplistic coverage that is all too common when covering impacts of climate variability on farm ecosystem functions and business profitability. Firstly, the journalist assumes most older farmers don’t believe climate change is happening: “… many of them (farmers) are yet to be convinced that man-made climate change is real.” It would be interesting to know what percentage is “many” and what type of farmer is being referred to – professional crop farmers, professional sheep and cattle grazing farmers, or part-time and lifestyle farmers who comprise approximately 55% of people classified by Australian Bureau of Statistics as farmers (they have a gross income less than $100,000 per year).

Secondly, the journalist assumes because a younger generation believes in climate change young farmers have a better knowledge for coping with it. Her case study of a young beef cattle farmer who has “… been adjusting the genetics of their cattle to make them even more drought-tolerant as their way of adapting to climate change.”, demonstrates how out of touch this journalist is with the key issues.

The drought tolerant cattle she refers to for adapting to climate change is misleading, they may be a breed that is heat tolerant and tick tolerant but if they are run on the farm at a stocking rate that exceeds the paddocks carrying capacity, the farm’s ecosystems will degrade as pasture cover is lost, soil erosion starts, costs rise with supplementary feeding and post drought pasture renovation. Matching stocking rate to paddock carrying capacity as the Purvis’s describe or demonstrated at Wambiana is a fundamental principle of grazing practice that ensures paddock ecosystems functions and cattle productivity (with reduced numbers) are maintained irrespective of rainfall.

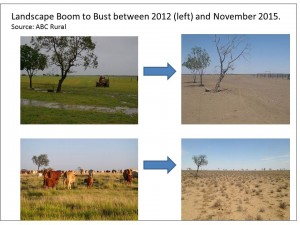

The importance of managing ground cover and preventing its loss was demonstrated in another ABC Rural news report in mid-December “Before and after: How the drought is biting in regional Australia”. The photo comparisons of tropically adapted cattle on lush green pasture taken in 2012 and the same paddock, now bare in 2015 shows how the destocking strategy early in a drought cycle is critical, the breed type makes no difference. It emphasises why the Purvis’s key management approaches need far wider adoption.

Had the journalist uncovered positive yearly trends for stocking rate/100mm of rainfall , the content of productive, palatable, perennial pasture species, and minimum ground cover levels allowed across the farm, then an argument could have been made for the young farmer adapting to climate change. From the data provided the message to the reader is to purchase Bos indicus infused beef cattle to cope with climate change.

The ABC journalist’s second example was similarly unrewarding as a case study demonstrating adapting to climate change. This example involved a vineyard where the farmer’s daughter took over and no longer practiced the water use irrigation methods her father used 20 years ago. No mention of the dramatic changes in irrigation scheduling and technology developed over the time period,

or of the rising cost of water and its significantly reduced availability. But even more misleading in the context of climate change was the statement ”To adapt (to climate change), she converted the entire vineyard to organic production methods.”

While organic farming is a personal preference it has no inherent advantage for adaptation to climate change. The organic farmer’s point of difference is not to use artificial inputs – chemicals and fertilisers. He or she is just as likely to use the same soil moisture monitoring, water scheduling and technology as the conventional farmer next door both of who want to buy less water and produce more tonnes per megalitre of water applied.

The danger with these examples is that they assume simple solutions rather than the reality of complex connected factors which need to be understood to farm successfully in a highly variable climate.

Managing a grazing or cropping business for resilience to climate variability seems to be closely correlated to managing for reduced greenhouse gas emissions, the question of belief in anthropogenic climate change is less important.

As for addressing climate change per se, the examples are of little value. Farmers can adopt strategies that reduce emissions or alternatively sequester carbon as demonstrated by Emissions Reduction Fund methodologies, but these are additional to everyday management. The common strategies most farmers have at their fingertips which will make a difference are:

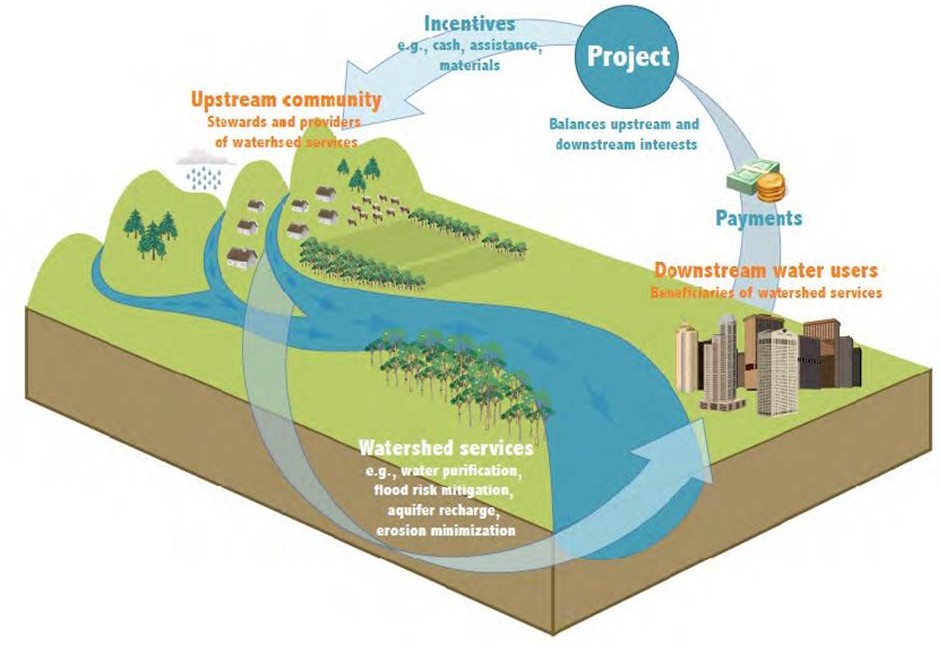

- Across Australia’s agricultural zone embrace reafforestation – plant trees and shrubs in corridors, riparian zones and blocks, and subsequently stagger harvesting for wood products and bioenergy and replanting. There is no reason why 5 -20% of most pasture or crop farmland cannot be replanted with forest or environmental plantings with the objective of achieving a carbon balance neutrality or to become a carbon sink.

- Intensive animal farms such as piggeries, dairies and feedlots can prevent emissions of methane from manure ponds by collecting the gas and using it for heat or energy production.

- Grazing farms can adopt holistic management to avoid booms and busts with ground cover.

- Cropping farmers use conservation farming techniques combined with precision technology and variable rate seed and fertiliser use.

- Monitor farm greenhouse gas balance with tools such as the Australian Farm Institute’s “farm gas” or the University of Melbourne’s farm greenhouse gas calculator. Then adopt strategies to improve the balance.

The ABC Rural Report “Before and after: How the drought is biting in regional Australia” highlights a re-occurring feature of farming and pastoral zone management during droughts in Australia, each farm ecosystem boom is followed eventually by an ecosystem bust, figure 6.

Figure 6: Grazing landscapes boom to bust as portrayed by ABC Rural in November 2015

For most of the media and politicians the bust becomes the main story and focus of attention. The ecosystem function and business successes of graziers practicing holistic management and farmers practicing conservation cropping with precision technology are usually ignored.

It is alarming that journalists and politicians are not asking more questions about why boom to bust scenarios are so widespread despite the billions of dollars spent since 1990 in state and federal NRM and landcare programs educating and funding farmers to embrace environmental management. Ironically the major agriculture policy settings associated with droughts involve programs to support farmers during the bust rather than preventing the major issue on livestock farms of stocking rate failing to match carrying capacity. Given increasing climate variability and an apparent increase since 1997 in the rate of failed wet seasons in the North and springs in the South, it is time drought policy included support for destocking businesses based on maintaining pasture ground cover at viable ecosystem function levels until regular rainfall returns.