National Landcare Program needs alternative funding policy for farming

By Patrick Francis

Summary

- Funding for landcare farming projects has become institutionalized and supports a range of NRM agencies for political purposes alongside bureaucratically determined environmental agendas

- There is no ongoing recognition for landcare farming practice change

- Emphasis continues on funding projects which chase slow adopters and laggards rather than rewarding farmers already producing ecosystem services outcomes in conjunction with food and fibre productivity

- A case study CMA 5 year plan demonstrates the futility of current funding approach.

- Most funded landcare farming projects are “reinventing the wheel” with respect to environmental management practice and grazing and cropping practice.

- A data base of landcare farming projects costing billions of dollars over the last 25 years is non-existent. Results from many projects have disappeared

- The latest Department of Agriculture and Department of Environment review is more bureaucratic window dressing about process rather than determining outcomes as the individual farm level. It’s as if landcare farmers have made no progress over the last 25 years of funding. The review also highlights how landcare farming has an identity crisis despite the fact that farmers manage approximately 60% of Australia’s land mass.

- The number of landcare groups in the 10 most professional farming districts of the Murrumbidgee river catchment have declined by 69% since 2004. It demonstrates that many farmers have been using environmentally compatible farming techniques for years and producing ecosystem services inconjunction with food and fibre production.

BACKGROUND QUOTES:

July 20th 2014 marks 25 years since Landcare was announced as a national initiative by former Prime Minister Bob Hawke on 20 July 1989.

Over the next four years (2014 – 2018), the Government will invest $1 billion through the National Landcare Program in projects that address environmental and sustainable agriculture issues. Landcare is a large and important program, but there is scope for improvement and an opportunity to deliver efficiencies. As part of this the government will be emphasising delivery of local priorities taking into account the views of community groups, particularly landcare groups.

Funding of more than $449 million has been approved for the Regional Delivery component of the Caring for our Country initiative (2013 – 2014). Regional Delivery provides funding for eligible regional natural resource management (NRM) organisations to help deliver the Caring for our Country initiative at the local and regional level.

Caring for our Country is the Government’s flagship initiative in natural resource management. Over the first five years from 2008-2013 it is providing more than $2 billion in funding.

Source: www.nrm.gov.au

Funding for landcare projects involving farmers is institutionalized across Australia. It has become a political sacred cow which ensures on-going funding irrespective of documented outcomes for on-farm ecosystem services in-conjunction with crop and livestock productivity and profitability. Politicians readily praise the work of landcarers but have limited and often irrelevant farm ecosystem improvement data to back up the accolades. And when farmers’ environmental credentials are sought to support food products for consumer appeal, landcare participation outcomes are rarely requested or acknowledged. No food or fibre companies associate their products with landcare on farm using the caring hands logo.

Natural Resource Management (NRM) agency funding application documents often give the impression that: most farmers have little or no knowledge of natural resources management across their farms; access to knowledge is limited and past knowledge is insufficient; “new” knowledge needs to be imparted; and developments in farmers’ knowledge and practices over the last 25 years are largely under-utilised.

The line between funding natural resource management innovation and recognition of standard everyday practices has become so blurred that projects are being funded that repeat what has been done and learnt one to three decades ago. When landcare started, funding was provided for on-farm projects which demonstrated innovation – a better way than past practice. The idea being that farmers involved would learn from the project and if suitable apply it on their own farms. It was never intended that farmers would be funded over and over again to repeat the project on their own farms. But that’s what has been happening over the last decade. Inspection of the successful 2013 – 14 Community Landcare Grants worth $10.7 million and the $449 million Regional Delivery grants confirm this.

The key words in project names have been changed to suit political agendas but in effect most of the outputs are no different to 20 years ago. Slip in the words climate adaptation or sustainability into a project title and approval is almost guaranteed today. In the 1990’s soil erosion, water table and salinity were the key words to application success. Next year funding application key words are likely to be “soil carbon” as the federal government’s Direct Action program gains momentum.

This situation has developed because landcare farming funding tradition has enormous regional political clout associated with volunteer groups, farm advisors and mini bureaucracies in particular Catchment Management Authorities.

There are other factors contributing to landcare farming funding being out of touch with continuously evolving farming practices, they include:

- The high percentage of farm businesses across Australia, which are part-time interests for their owners. ABS data shows 55% of farms have a gross value of agricultural production less than $100,000 per year. The owners of most of these farms would run them on a part-time or lifestyle basis and they are concentrated along coastal districts and in southern and eastern Australia’s higher rainfall corridor within 300km of a capital city. The owners are likely to have professional qualifications outside of agriculture where they work full-time, so much of practice change which has already happened is unknown to them.

- There is no national repository of reports generated from landcare funded projects and trials. Tens of thousands of on-farm projects have been funded over the last 25 years but the data is not collated. Apart from this many project/trial reports are provided on individual group web sites in an abbreviated version, with more detailed information held by project coordinators associated with a local consultancy or co-funding institutions like Universities and Departments of Primary Industries and Environment. Access to the co-authors after a few years is often lost as the coordinators/researchers have moved on. Many landcare groups have closed down over the

last decade and their project data has been lost. For instance in the Murrumbidgee catchment 73 out of 106 landcare groups in ten networks have closed since 2004. - Most state governments have significantly reduced their farm extension divisions which means part-time and lifestyle farm owners have little or no access to professional advice without paying for it at the same rates as full-time, far larger farm owners. Landcare farming projects have become a “claytons” and low cost extension service for state governments, particularly for servicing part-time and lifestyle owners. Landcare farming projects are not only free to participate in, some projects will pay for various input costs involved, for example soil tests, perennial pasture seed, alternative fertilisers and soil ameliorants, sub-divisional fencing etc.

- Landcare farming project funding guidelines are topic focused and short-term. In contrast each farm involves diverse agricultural and natural eco-systems in a highly variable climate, so positive change involves understanding the ecosystems connectivity and complexity over changing climatic conditions. This is referred to as holistic management by some farmers. Landcare farming projects do not embrace holism as there are too many variables involved and their funded time span of up to three years is too short in a variable climate.

- Finally none of the national programs since funding started has audited on-farm performance across a wide range of environment and productivity indicators on a long-term basis. This has two consequences – it means agencies don’t know how farmers, particularly the innovators, are performing with respect to producing environmental services; and secondly agency personnel continually repeat projects because they have no benchmarks to compare with. Project success criteria are usually superficial at best and seldom require on-farm ecosystem services trend data.

But how long can those involved keep justifying funding projects that are well past being innovative and should be treated as expected practice or management? If some farmers are not prepared to pay for knowledge or refuse to adopt a landcare farming practice, which has been part of methodology change for decades why should funding continue to be provided to attract them to change?

In contrast, the majority of professional farmers (a farm cash income in excess of $100,000 per year) have made it their business to be aware of how their management impacts ecosystem services and productivity because if they are not aware they would struggle to stay in business. Most don’t rely on landcare projects for new knowledge, if they haven’t already learnt from experience and training, they pay professionals for advice. The two great Australian examples of economic and environmentally induced practice change over the last 25 years are the adoption of conservation farming techniques by professional grain farmers and holistic grazing management by livestock farmers, particularly in the rangelands.

Ironically the winners of the state and national Landcare Primary Producer Awards over the last two decades stand out because of their holistic approach to landcare farming. They have made the transition to holistic decision making for their farm businesses because it produces better business as well as environmental outcomes.

A path forward

What needs to be done for landcare farming in Australia is to rethink how the funds available can be better utilised to support continuing improvement to ecosystem services on farms, irrespective of their size and professionalism. It’s time to move from a project focus to recognition of ecosystems services outcomes and reward farmers for documented positive trends in soil health, greenhouse gas emissions, biodiversity, surface cover, water use efficiency and productivity indicators (see indicators story on this web site). That is reward positive stewardship. It’s a carrot approach which encourages farmers to use existing knowledge rather than requiring it to be identified again and again.

Secondly, an outcomes reward approach is important for long-term maintenance of conservation, riparian and forest areas on private land where they have been set aside from grazing and cropping to produce ecosystem services. Such conservation areas require on-going maintenance associated with feral animals, weeds, fire control, dieback, fencing and possibly replanting. This is currently ignored for all but rare or endangered natural habitat on private land where “tender” schemes sometimes provide financial support for maintenance.

Thirdly, it will give credibility to the long unsubstantiated claims from politicians and producer organisations made about Australia’s “clean and green” farming systems. At this point of time only the “clean” component can be verified in scientific terms.

Persisting with recalcitrants

A recent Victorian CMA report illustrates the futility creeping into landcare farming funding. The particular CMA involved is a valuable case study as it comprises one of the nation’s most productive farming districts where a high percentage of owners conduct professional full-time cropping and livestock businesses.

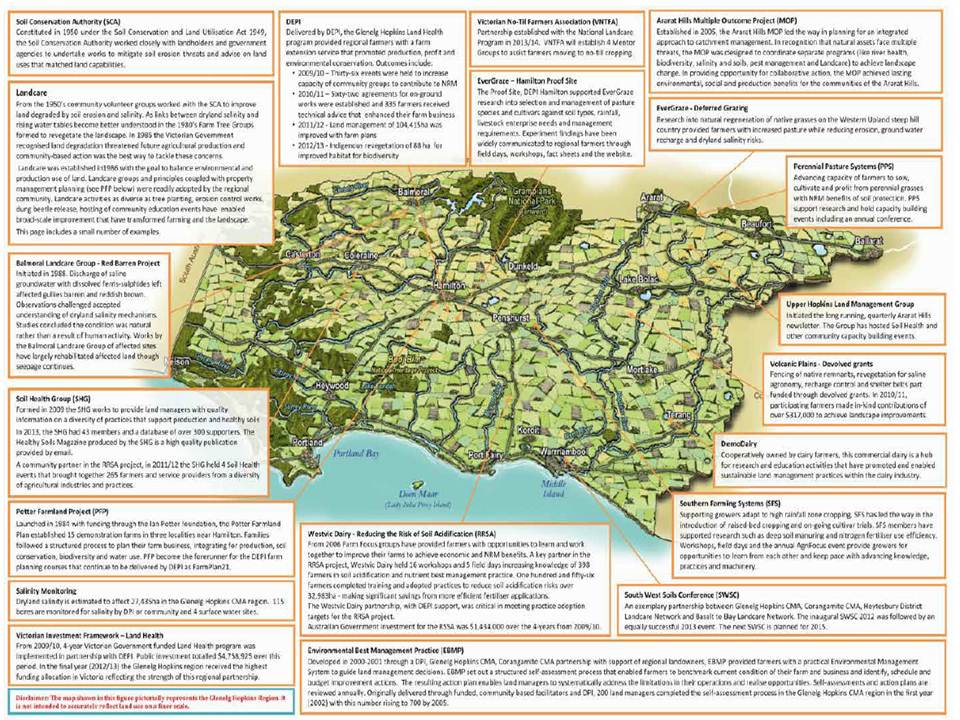

The Glenelg Hopkins CMA Soil Health Strategy 2014 to 2019 is a comprehensive document, outlining extensive inputs since the 1950’s to improve farm ecosystems. Its presents a snapshot of many of the most important inputs to farmers’ knowledge over the years, figure 1. Millions of dollars have been spent but what are the outcomes? On individual farms across the catchment outcomes are plain to see, but there is little documented evidence available or recognition given.

Figure 1: The Glenelg Hopkins CMA region boasts an enormous history of innovative NRM and farming practice projects and extension since the 1980’s. Source: Glenelg Hopkins CMA soil health strategy 2014 – 2019.

One possible chance to recognise farmers for making a difference to ecosystem services on their farms faded quickly in the early 2000’s when an Environmental Management System was launched in the catchment, modelled on the highly successful Canadian EMS program. Figure 1 describes the EMS program and states that by 2005 over 700 farmers participated but then the funding for facilitators ran out and the program died in favour of new initiatives thought to be more compelling by politicians and NRM bureaucrats. The irony being EMS is holistic and embraces all the issues relevant to improving farm ecosystem services in a variable climate and connects positive trends on farm to food and fibre consumers.

So after more than two decades of funded programs since landcare started in the catchment what has been achieved? Analysis of catchment farmers surveyed about which organisations influence their farm management showed:

* 9% participated in Caring for our Country programs

- 5.5% participated in state government projects

- 8% had improved understanding of land management and environmental issues

- 10% sought information or advice from regional NRM organisations, and

- 11% sought information or advice from the state DEPI

Yet the Glenelg Hopkins CMA region contains one of the most productive farming areas in Australia due to its high quality soils, moderate rainfall and lack of significant pest issues. It rates as:

- The largest producer of wool nationally

- The largest total value for sheep, lambs and wool.

- 10th for number of cattle

- 2nd for number of sheep

- 2nd for milk production

- 6th for agricultural production gross value and

- Has 81% of land used for agriculture.

There is no evidence presented that a soil health strategy is needed for the catchment, there is only an assumption made that it is required. Despite the outstanding production from the district and the participation by a small percentage of farmers with NRM agencies over 50 years involving millions of dollars of government funding, there is no public data available on soil health benchmark trends.

The strategy initially gives the impression that most farmers are not embracing changing circumstances and are not equipped to cope with emerging developments:

- “Climate change: Without major adaptations, agriculture may struggle even to maintain current production

- Climate change and soils: Agriculture and forestry are likely to be impacted through impacts on water availability, land health and agricultural yields.

- Providing for a Word Population: The achievement of increasing agricultural outputs with reduced inputs will demand new thinking and innovation in agricultural land management practices.”

But most professional farmers are constantly embracing change in environmental and economic circumstances and adapting management to suit. Many are also allocating productive land to conservation and forestry to assist with providing more ecosystem services.

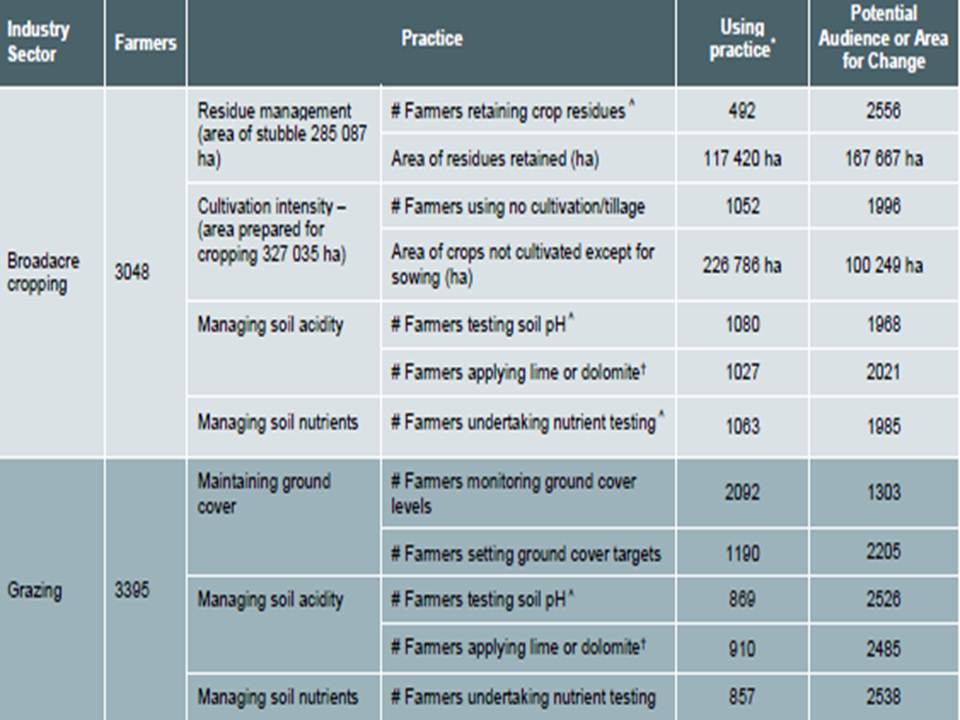

The strategy then refers to some ABS data which tracks a small number of practice change

characteristic in each CMA region through the Agricultural Resource Management Survey (ARMS) using 2007 – 08 results, Table 1 . Despite only monitoring five practice changes, the survey demonstrates around 50% of the catchment’s farmers have changed practices such as soil testing, retaining crop residues and monitoring ground cover. It’s not surprising for commercial reasons.

Table 1: Practice change has happened as this Agricultural Resource Management Survey (ARMS) 2007 – 08 data shows.

Even the CMA admits “…that good progress is being made in many practice areas within the Glenelg Hopkins regions.” But it contends “the research also highlights there is an opportunity to undertake further work in encouraging … businesses (to adopt changed practices)”.

Such an assertion is questionable because farmers who have not adopted practice change after years of opportunity to do so (as evidenced by figure 1 programs) may never be interested in changing for a wide range of reasons. This demonstrates the common reluctance by NRM agencies to accept the 25 year old funded project model needs to change.

The Authority justifies seeking more funding for the new Soil Health Strategy on the premise that a percentage of the recalcitrant farmers can be brought on-side. This is despite the fact that survey shows only about 10% of farmers utilise public resources for information. The Authority needs $2,100,475 over five years from the Regional Delivery Sustainable Agriculture stream. For this outlay the Authority has produced “Output Targets” for 30 June 2018. The targets include:

- 145 farming entities have adopted more sustainable land management practices

- 24 farming entities have trialed innovative land management practices

- 630 farming entities have improved capacity to manage natural resources for ecosystem services.

These are soft, fairly nebulous targets and may not contribute to the regions ecosystem services and productive agriculture capacity if the farming entities involved are mostly part-time businesses or lifestyle farms.

What if the Authority took a different approach and offered the 630 farming entities $1000 to undertake an Environment Best Management Practice program on their farms for five years? For a significantly, less outlay of $630,000 the farming entities could achieve the same targets with other entities knocking on the Authority’s door to be involved for the same incentive payment.

In 2013 – 14 the Glenelg Hopkins CMA received $10,881,900 for regional delivery projects. Of the total approximately $3.2 million is for the sustainable agricultural stream and $7.6 million for the sustainable environment stream. In the nrm.org.au web description of how this money will be used in the agricultural stream the application says: “Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority will build the farmers’ capacity to make and implement land management decisions to improve soil condition, increase or maintain production and protect the natural resource base.”

Another obscure ‘feel good’ statement that is likely to have little relevance to most professional farmers who are already striving to “increase or maintain production”. Unless the Glenelg Hopkins CMA derives a system of retrieving monitoring data from farmers they will never know if any initiatives they introduce are needed in the first place or if implemented, produce cost effective outcomes.

While the Glenelg Hopkins CMA is used as an example in this article the same issues of effectiveness and accountability pervade all the CMAs and it’s why questions must be asked about the $449 million allocated to them in 2013 – 14.

Landcare group projects

Similar questions about accountability and relevance can also be asked of landcare groups who received $10.7 million in 2013 – 14 Community Landcare Grants. In Victoria 53 landcare groups received an average of $43,000 for each project. Only one out of 53 projects was novel, most of the others have been the focus of research and extension for years. There are a small number of projects which have received funding for events or leadership programs and are not about on-farm practice change. The same situation applies to most of the projects funded in other states.

What is hard to comprehend is that there are still farm based projects being funded for weed control, rotational grazing, soil acidity, direct seeding crops and pasture, wind erosion in the Mallee, perennial pastures, grazing native grasslands, etc. These are all topics that have been researched, written about and extended to farmers for decades.

Public land landcare

Funding for community landcare groups through community environment grants to work on public land involves an entirely different set of circumstances. The individuals involved are volunteers, they have no commercial imperative for producing ecosystem services outcomes, so their funding remains appropriate under current guidelines. This is not necessarily the case however, for environment grants on private land.

Outside of innovation projects it is time individual farmers were only rewarded for improved landscape amenity via monitored improvement in ecosystem services. So funding for planting trees, fencing off biolinks, replanting riparian areas, and protecting remnant vegetation on private land should end and where appropriate be replaced with some form of medium term (10 to 20 years) stewardship reward farmers can use to help maintain such areas and biodiversity.

About the author

Patrick Francis has a long involvement in landcare farming. He was chair of a landcare group for farmers near Romsey, Victoria between 1991 and 1999. His own Moffitts Farm is a case study for a 2003 published farm Environmental Management System book produced by Rural Industries Research & Development Corporation. Landcare and farmer groups visit Moffitts Farm for workshops and farm walks. As editor of Australian Farm Journal he initiated a new national landcare magazine starting in 1996 as Sustainable Farming magazine which became Australian Landcare magazine in 1998. He was editor of the magazine until it ceased publication in June 2012. He has been on many judging panels for Victorian and national landcare primary producer awards. Find out more: visit www.moffittsfarm.com.au

Followup articles:

Landcare review questions dodge farmers positive outcomes

Direct tree seeding project is back to the 1990’s