Zooming in on northern Australia’s “food bowl” practicalities

Nuffield Scholar Aaron Sanderson has injected some practical farming home truths into claims that Australia’s Top End can become a food bowl for Asia. His research found that in comparison with tropical agriculture in developing countries northern Australia has many drawbacks and small holders farmers are far more efficient at food production than they are generally given credit for. This is an edited version of his final report.

Scholarship summary

My key findings suggest that northern Australia is quite different to most other tropical parts of the world. For instance, the monsoonal weather pattern happens in northern Australia, but the duration and amount of precipitation is often quite a bit less than many other areas where field crops are raised.

Partly because of this we tend to concentrate on farming the more fertile heavier clay based soils that hold moisture better, and then machine trafficability becomes an issue during the wet periods.

There is a severe lack of labour in the north to undertake farming tasks, which is at odds with most of the tropical world where manual labour is a feature. Supply of this labour is becoming a problem but as far as general population goes, people are in abundance.

Farming systems in developing countries have not changed a great deal in generations. The exception to this is Brazil that has embraced research and development, and coupled with abundant natural resources, has emerged to become one of the world’s production powerhouses.

Australian farmers do a remarkable job as far as efficient production systems go. While looking over the fence is always good for a reference point, in this case there are not a lot of take home ideas to be gleaned from most of the farming areas in the tropical world. The exception is perhaps Brazil who, with large areas of well drained soils and abundant rainfall over a six month wet season, have mastered the art of running large, technologically advanced farms in this environment and will continue to improve with very organized research and development programs.

Northern Australia is a region of the world that has the classic monsoonal climate characterized by a summer wet season and a dry winter rainfall season. There is currently a renewed interest in further development across the North of Australia to take advantage of the perceived vast areas of arable land and abundant water supplies.

I initially applied to Nuffield as a direct result of moving between two different farms and finding that I had to re-apply all my knowledge to areas that were initially simple to me. I moved from broadacre farming in Central Queensland to The Burdekin in North Queensland. Although this is only a very short distance when looking at a map, I was extremely surprised to find that I had to relearn simple farming techniques.

For my scholarship research was conducted primarily by talking to growers on their farms, in their fields, and seeing first hand their operations. I visited growers in China, the Philippines, India, Thailand, Northern Australia, Brazil, and Mexico.

Farming systems throughout tropical areas of the world vary greatly, despite the fact that most crops produced are relatively common. Some of the major influences include soils, climate and precipitation. In addition, cultural and historical development plays a large role in defining how these systems look today.

This does not mean that these parts of the world (in developing countries) cannot produce good high yielding crops – on the contrary. It is remarkable that high quality crops can often be produced with so little.

Climate differences

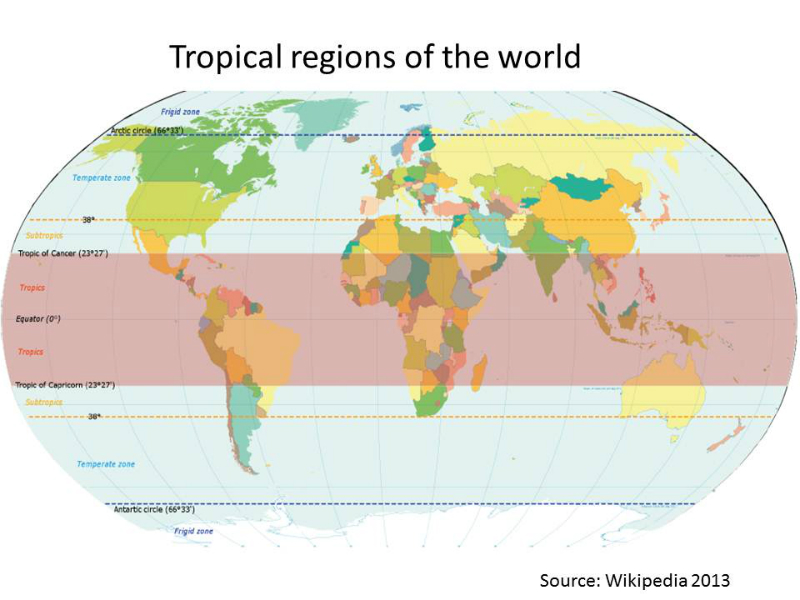

The tropical areas of the world fall into the region between the Tropic of Capricorn in the South and the Tropic of Cancer in the North (between latitude 23 degrees North and South) and have an incredibly strong monsoonal weather pattern. These areas have a distinct delineation between wet and dry seasons in terms of rainfall, have large quantities of rain and high intensity, but do not have great variations in temperature (Attard, 2007).

The wet season is the time of the year when most of the precipitation occurs and can last for months. There are many places where excess rainfall during the wet season is stored in one form or another (typically in below ground aquifers or above ground dams) and then applied as irrigation to subsequent crops during the drier months.

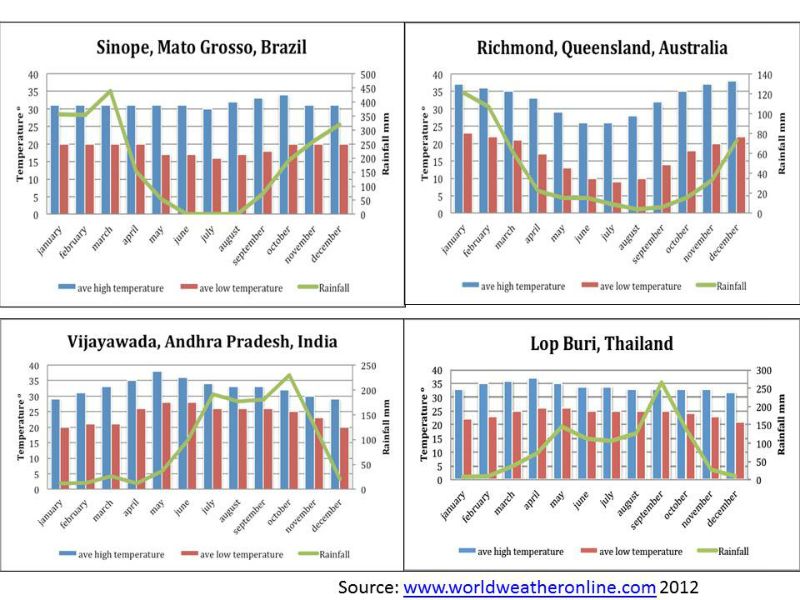

Although generalisations are made about the climate across the tropics, variability certainly exists. The wet seasons usually correspond to the summer months of the respective hemisphere but rainfall distribution can still be quite different and require different management to work with. Figures 2 illustrates four distinct areas. Although the temperatures correspond quite well with each other, there are two things that really stand out:

- The extremes in monthly precipitation totals of the Mato Grosso, deep in the Brazilian interior, range from very intense summer rain to virtually completely dry in winter months.

- How dry Richmond, Queensland is in comparison to those selected localities. Still situated very much in the tropics, Richmond has an almost arid climate that makes cropping a challenge. The enterprises that operate in this area rely on storing water from the summer for later use.

Soil differences

Soil types and characteristics are literally the building blocks of any farming system and probably have more effect on how operations are carried out than any other component in that system. The soil is a complex living ecosystem with chemical, physical and biological systems interacting to enable our crops to grow. Agricultural soils vary greatly around the world and can range from low water holding capacity progressing through the loams to heavy dark clay based soils which can hold enough plant available water to grow an entire crop.

Because of high evaporation rates in the warmer parts of the world, a high proportion of clay is a desirable trait due to the ability for those soils to hold moisture and nutrients for future use when rainfall is limited. In a country such as Australia, dark clay soils can be considered some of the best when asked to grow rain fed or irrigated crops, as the number of dry days far outnumber the wet. However, one of the limitations of heavy (high clay content) soils, when matched with mechanized farming, is the trafficability of those soils when wet.

Over the past two decades, the developed world has experienced farm machinery growing in size. The sole reason for change was to accommodate more efficient farm operations in a generation that has experienced tighter economics and a shrinking labour supply. It is a frequent occurrence for tractors to effectively sit idle for months throughout Queensland’s rainy seasons as the wet soils do not possess the capability to successfully hold the tractors weight. On the other hand, Indian farmers who use oxen as their farming tool of choice do not face this problem.

The size of the tractor undoubtedly has a bearing on exactly how well the machine will perform on wet ground. For instance, a common tractor across India and Thailand is a John Deere 5410 model rated at 81 horsepower and having an operating weight of approximately 2700 kg (tractordata.com). Contrast this with a common row crop tractor used in Australia such as a John Deere 8430. This tractor has a horsepower rating of 330 horsepower and an operating weight of over 13 000 kg.

Almost as an exception to the rule are Brazil’s vast areas of free-draining red sandy loams. Combined with generous rainfall, these soils enable the development of a farming system that can utilize large machinery as machine traffic can be supported quite quickly after rainfall. For example, a clay type soil receiving 25 mm of rain in an afternoon storm on successive days might not dry out enough to drive on until there are five or more days of no rain, while on the sandy loams farm operations can quite often continue the next morning (Blair, 2011). Soils of this type have allowed Brazil to develop a farming system that simultaneously allows harvesting of one crop whilst a second one is being established in the middle of their wet season.

Agronomic differences

The agronomic aspect of a farming system is often the area where the farmer can have the most input in regards to the day to day business of producing the crop. Key activities include preparation of the seed bed, planting of the seed, and nurturing of the crop through to harvest.

Written records detailing agronomic practices were almost impossible to obtain in some developing countries where information is passed on verbally from farmer to farmer and generation to generation (Kumar, 2011). As a result of this, information was gathered through observing farm practices, communicating with the farmer and documenting useful recollections.

In Asia some beautiful soil – deep, dark, soft, and fertile, exist in many areas. Tillage involving deep ploughing followed by multiple passes of lighter disc machines is common prior to planting on farms where mechanization has taken over. This, combined with burning of some residue is regularly undertaken to allow planting machinery to operate unhindered.

Significant areas in Asia heavily rely on human and animal labour for cropping. Figure 6 illustrates an Indian farmer inter-row cultivating cotton with a pair of Brahman ox attached to the front of a steel and timber single row cultivator. The accuracy and quality of the job performed is not to be underestimated. The animal had the ability to walk in a straight line throughout the entirety of the process. The Indian farmers were curious as to how many farmers in Australia still farm with an ox.

Brazil is almost the other end of the spectrum as far as machinery and soil preparation goes. In the broadacre areas it was apparent that large current generation machinery was being utilized in a predominately no till farming system similar to how it is practiced on Australian farms. Soybeans are planted as the rainy season begins in October and as it is harvested in January and February, corn or cotton is no till planted immediately behind the header to take advantage of the rest of the wet season (Bruch, 2011). That corn stubble cover is then retained and soybean planted straight into it later in the year.

Planting seed populations do not seem to vary much in size. For example, a corn population of roughly 62 000 plants per hectare seems to be the desired planting rate in most areas visited, including Australia. It was surprising to find that hybrid seeds from multinational seed companies were so extensively used.

Another interesting finding is that even in these developing countries, agricultural chemicals are in widespread use. The same products are available around the world, with their presence seen regularly on our shelves and a widespread use within the industry. India’s weed control program looks very similar to the program in Brazil, Thailand and other locations where a similar crop rotation is used. What does vary greatly however, is application technology. While the Brazilians are using current generation self-propelled sprayers, similar to what we see here, application in most of Asia is rudimentary.

Crop nutrition differences

An expectation that mixed farming (crops and animals) would be the norm across many of the areas that were visited was not realized. Integrating animals into a cropping system through the use of grazing stubbles and/or pasture crops is a way of cycling nutrients to enhance soil fertility for subsequent crops. Nutrient removal through the harvesting of crops means that eventually those nutrients will have to be returned through one system or another or significant fertility decline will occur. Subsistence farming is the most graphic illustration of this.

A piece of land is cleared and cropped until the production declines and then a new piece of land is brought into production while the last piece is let to revert back to its former state to allow nature to regenerate it (Ninnes, 2011). This is a very slow and drawn out process.

Many areas visited have been farmed for generations and the fact that the soil is still producing suggests there have been farming systems in place that enabled nutrient cycling and fertility regeneration to occur sufficiently to maintain productivity.

From observation, the reliance on manufactured fertiliser is currently almost universal. Farmers in all areas visited were investing heavily in fertiliser, of the same composition. These same farmers state that fertiliser is becoming too expensive and rates need to continually increase to maintain production levels. Urea appeared to be the most common fertiliser as well as large amounts of solid products supplying phosphorus.

Rates of product used also appeared, with possibly the exception of Brazil, to be quite universal and in line with what growers in Australia would reasonably expect to use. Approximately 20 kg per hectare of nitrogen per tonne of expected yield of maize seemed to be used in most places. In Brazil, the double crop of soybeans in the rotation allows them to use rates in the order of 15 kg/ha/tonne of yield (Ferracuti, 2011).

Labour differences

The most popular conversation topic that came up amongst farmers right across the world is labour. The supply of people to do the manual tasks in agriculture seems to be a problem not limited to any particular country or demographic.

The other interesting component of this topic is the idea that unskilled labour can be better sourced from countries other than your own. For example, the US has a large reliance on labour from Mexico, Western Europe from Eastern Europe, Thailand from Myanmar, India from Pakistan and Australia from Asia.

The shift away from agriculture to urban areas for better employment is not a new concept but as you look at countries with different levels of economic status, a common denominator is that agriculture is often at the less desirable end of favoured jobs. For example, in India and China especially, the growth of manufacturing and electronic industries are creating an enormous drain on labour for traditional industries such as agriculture.

It is hard to imagine that in these countries with very high population levels, and in comparison to Australia, a very decentralized demographic, that there could be a labour shortage but the emergence of businesses in rural areas manufacturing consumer goods or electronic parts has put a strain on human resources available for food production. A labourer in Thailand can now make the choice of working on a farm and harvesting corn by hand, dragging a large hessian sack through a three metre high corn crop in 35 degree heat and 95% humidity or worse, or assembling electronic circuit boards in a clean air-conditioned building. It is often a simple choice, regardless of remuneration (Pongpanich, 2011).

Social issue differences

In many parts of the tropical world, even ignoring country boundaries, the social fabric of society is the determining factor on how agriculture operates, especially where producing food for yourself, family and immediate neighbours is the number one objective. The land tenure systems are wide and varied as well, but there is much more involvement of the greater community in what happens on the piece of land that you are farming than we in the western world are used to (Gonzales, 2011).

It is not necessarily government regulation, although there is always a degree of that, but more practical and hands on issues that have the greatest effects. Dr Ken Sayre from the Global Conservation Agriculture Program based in Mexico at CIMMYT, says that in his travels around the third world trying to promote conservation agriculture as a farming system, these social issues can be some of the most problematic. He says a farmer could be keen to embrace conservation farming techniques to enhance a cropping program, but it becomes very difficult when the accepted practice is for the farmer down the road to utilize your crop stubbles to feed his goats until there was nothing left. Without your stubble, he would not be able to run his goats and by definition be out of business. Another example is when the crop residue left behind in your cotton field is gathered up by the local villagers to provide fuel for their cooking fires and other domestic uses (Gallegos, 2011).

Why Northern Australia is different

There is currently another wave of interest in further development of the perceived large areas of arable land and abundant water supplies that exist across the northern areas of Western Australia, the Northern Territory and Queensland. Recent visits to the Ord River Irrigation Area and time spent looking at country around Katherine in the Northern Territory as well as a trip across Queensland to the Gulf of Carpentaria, have provided an insight into farming in Northern Australia.

The underlying feature of these regions is remoteness. They are simply a long way from major business centres that support field crop style agriculture. This means that to get a drum of chemical, bags of seed or fertiliser or to ship produce out, logistically it becomes a large and costly organizational issue.

However, those issues aside, the methodology required to physically produce a crop in the North is not greatly different to that of more southern or temperate localities. The difference becomes management. Sure, they might use some slightly different genetics, but it can be in the resultant physiology of the plant that needs to be accounted for. Because of the growing conditions, the size and shape of the leaves on a cotton plant grown in North Queensland differs markedly to one at Moree in New South Wales, and has large implications to the way the crop is managed to get it to set and retain fruit.

A weed control program using residual herbicides in the tropics could still look quite similar to a southern one but there is a tendency for rates to be significantly higher to overcome more rapid breakdown of those herbicides due to heat, moisture and biological activity.

Also, retaining nutrients through the wet season can also be a challenge due to large amounts of rainfall, especially when it comes to highly mobile nutrients such as Nitrogen.

Were there lessons to be learnt in other tropical areas around the world that could be used in farming across the north of this country? Possibly; but not a lot that are directly applicable. There are some hints relating to machinery size and use of tracks rather than wheels and weed control options to herbicides

Take home message

There are no silver bullets hiding elsewhere in the world for overcoming the operational problems in the country’s northern region. Each area of the world comes up with its own methods and solutions in response to the environment in which it operates. This includes the physical environment – such as climate and weather –and is also shaped by history and culture and the availability of resources. This makes comparing farming systems, or even potential farming systems in Northern Australia, to other parts of the tropical world a virtual impossibility.

The natural resources on offer across northern Australia vary quite considerably and are unique in the tropical world. Except for some small coastal areas, we do not have an abundance of rainfall. Northern Australia generally receives substantially less rainfall than many other tropical areas, with most rainfall predominately arriving over a short period of time. The wet season is often very short, not the 6 to 8 months enjoyed by tropical Asia. Northern Australia does not have the vast areas of well drained arable soils that Brazil or Thailand enjoys; rather we have a patchwork of heavy soils scattered across the northern region. This makes it difficult to get critical mass together to offer infrastructure and support services to the growers operating there.

While the lack of available labour situation is an issue all over the world, it is especially difficult in Australia. Australia has a vast region across this top end that just simply does not have a large population and those population centres are often long distances away from existing or potential farming areas. In other areas, the populations of the countries are mostly much higher with a larger number of people engaged in agriculture. Even in more remote areas, there are quite high numbers of people, often in small villages, which can supply labour.

There is more common ground across the world when it comes to agronomics. Supply of field crop genetics by large multinational companies is almost universal, as is supply of farm chemicals and fertilisers. The rate of use of these is also similar across the board. Yields of crops generally reflect the ability of the growers to supply inputs to those crops which is no different anywhere in the world.

The big issues in the north of this country continue to be the same as they have been for many years. It is simply a very large place and logistics and its associated costs continue to be the overriding factor. As a result, farming systems issues continue to take a back seat to other problems. Support and infrastructure, proximity to markets, and the availability of skills and labour will continue to be the debated topics for this part of the world.

Find out more:

Aaron Sanderson, West End Qld, 0428 186 497, aarao43@gmail.com The full report is available at Nuffield Australia, www.nuffield.com.au