Farm profitability ignored in overseas investor and Food Bowl debates

By Patrick Francis

Key points

- Most farmers have a different agenda to the rest of agriculture’s sectors when it comes to what is important for the future of Australia’s broadacre agriculture.

- Most farmers want to see how initiatives such as foreign investment in Australia’s agribusinesses actually boost their business profitability.

- Similarly farmers want to know why selling commodities like more wheat to Indonesia, more live sheep to the Middle East, more wool and beef into China isn’t improving their business profitability.

- Politicians, agri-industry leaders, academics and agribusinesses usually ignore market price trends, return on investment trends, farm ecosystem environmental health trends and changing consumer food and fibre requirements in favour of advocating boosting productivity as the way for Australian farmers to increase profitability.

- More than 50% of broadacre enterprises, defined as farms with greater than $20,000 annual gross income, are part-time or lifestyle enterprises earning less than $100,000 gross income per year. The Top 25% of professional broadacre businesses are close to optimum productivity in relation to soil water efficiency and environmental and animal welfare integrity.

- There are a host of initiatives which demonstrate that farmers who become partners in the supply chain and can contribute transparent quality assurance, food safety and credence values associating their products with environmental management, natural production, animal welfare and family farms are becoming preferred suppliers to domestic and overseas consumers.

- The commodity culture which sunk the nation’s pre-eminent agricultural sector up until 1991 – Merino wool production, remains the dominant paradigm in grains, wool, sheep meats and live animal exports. Dairy and beef are standouts in shifting away from the commodity culture.

Our grain and livestock farmers are often quoted by industry leaders as being world leaders in terms of production efficiency but there is a deathly silence about their businesses profitability.

It is interesting to review the discussion around Australian agriculture’s role in world food production and the importance of foreign investment to enhance that role. The overwhelming opinion seems to be that Australian farmers are exceptionally well placed to take advantage of increasing demand for food from a growing world population, especially amongst the increasing percentage of middle income earners in developing Asian countries. To take advantage of these market opportunities many industry analysts contend agriculture needs to attract overseas investors.

While this message is loud and clear from bankers, investment consultants, politicians, and agribusiness CEO’s, it invariably omits any reference to the relationship of the farm gate price for commodities and the final price it commands in consumers’ hands.

In other words where is the profit to be derived for Australia’s grain and livestock farmers to keep them in businesses supplying livestock, grain and milk to processors in Australia or overseas? If this issue was of any concern to investors then the precarious financial state of many professional farms would be highlighted then analysed to demonstrate how it can be changed. I am yet to sight any foreign investor supporters or Asian food bowl opportunity advocates highlight data such as:

- Farmers return on investment over last 10 years

- Farmers terms of trade over the last 30 years

- Real price trends for commodities over the last 10 years and outlook for next 10

- Real price trends for fixed and variable inputs over the last 10 years and outlook and next 10

- Total factor productivity trends for the last three decades

- On-farm environmental trends and soil health for the last three decades.

If this data was put together by takeover agribusinesses like ADM for GrainCorp suppliers, and Saputo for Warrnambool Cheese and Butter suppliers, then well informed debate about the merits or otherwise of their takeover rationale and justification could be undertaken.

As it stands no-one except the farmers in the industries seems to care about where the on-farm profits in these sectors exist and which part of the supply chain stands to gain most from the take overs.

The acceptance of the ADM by the GrainCorp board of directors highlights this issue. Is there any evidence that grain farmers will operate more profitably as a result of this takeover. If there is, no-one has detailed it. CEO Alison Watkins waxed lyrical the benefits to farmers of grains industry deregulation at a recent Australian Farm Institute conference and promoted the takeover offer.

“Here is a company (ADM) that is so confident about our product, capability and future that wants to invest billions of dollars here, “she told the conference. But there was no mention of the trends in profitability of grain grower suppliers to her company over the last decade. GrainCorp’s annual report also highlights how successful it has been over the last three years as an international grain business. But where does its financial success lie, principally in grain logistics and more recently in grain processing with canola. The same position holds for Saputo in dairy processing. It’s time analysis of the impact of take-over offers on farmers profitability is examined in detail.

Commidity prices to remain static

There is plenty of anecdotal evidence emerging that professional farmers in both the dairy, grains and red meat sectors are under enormous pressure to maintain profitability. And according to the OECD-FAO report released earlier this year, prospects for improvement are not strong because despite growing demand, prices for commodities are constantly under downward pressure from the entire post-farm gate demand chain, figure 1.

One of the most interesting pieces of evidence for this can be found in annual reports from public companies operating as commodity producers. Prime Ag and AACo are excellent Australian examples. Prime Ag has been financially unsuccessful as a major grain grower despite having outstanding properties. AACo which has the largest cattle herd in Australia and all the associated economies of scale has struggled to give shareholders a return on investment and has embarked on a new business direction into meat processing, value adding and brand marketing. The bottom line for both companies is that farming commodities is an extremely difficult business on which to make an acceptable return on investment – yet that is what Australia’s family farmers are attempting.

The Australian Farm Institute’s Mick Keogh highlighted this at a recent conference when he said: “Agriculture (farming) is a price taker and cost receiver and the increasing volatility of the market has made it harder to repay significant borrowings.”

What is not often mentioned in the rural media is that farming is now a part-time job for many land owners, in the broadacre sheep and beef cattle grazing areas. ABS data shows that the majority of these farmers (defined as having income from farming in excess of $20,000 per year) have a gross farm income less than $100,000 per year. Keogh said about 95% of net income on these farms was derived from off-farm wages. The situation in dairying and cropping is significantly different as 90% or more of farmers in these two sectors are professionals mainly because of the high amounts of capital invested in land/cows for dairying and land/machinery for cropping. Nevertheless some off-farm income is still important for these businesses to survive.

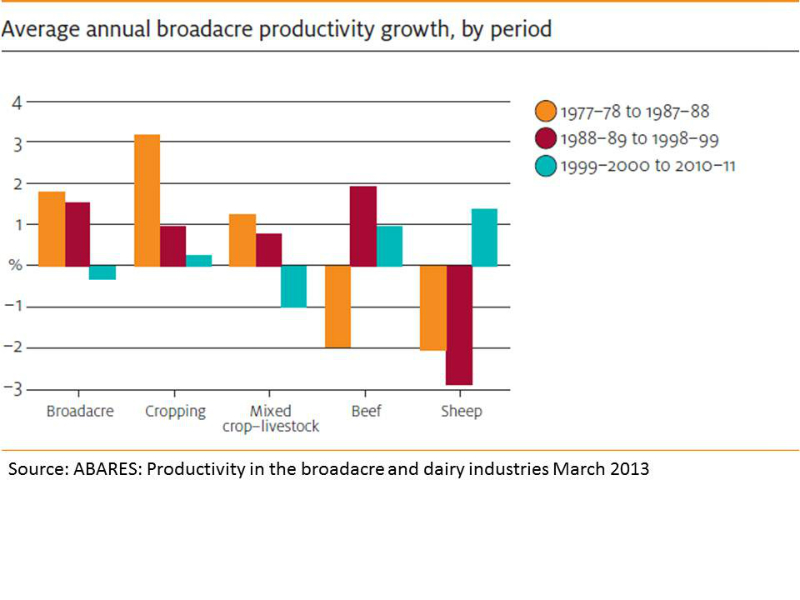

Another disappointing component of the debate about overseas agribusiness take-overs is the lack of recognition for the need to involve farmers further along the demand chain and reward them for adding value be it physical or credence. Except for on-going incremental improvements associated with soil health, technological aids and plant and animal genetics, the productivity bubble of the 1980’s and 90’s for broadacre agriculture has in the main burst for the Top 25% of farmers. The optimum output associated with water use efficiency (per 100 mm rainfall), environmental health, animal welfare and social health has been reached for most of these farmers. This is somewhat reflected in the decline in Total Factor Productivity, figure 3, over the last decade compared to the previous two decades and the emergence amongst many top businesses for maintaining environmental integrity year in year out irrespective of rainfall.

Surprisingly the federal government and at least two state governments don’t recognise these as an achievement for their top farmers and continue to push a policy of doubling current productivity as a means to achieving greater profitability. It’s an approach which is enthusiastically supported by many agribusinesses as it ensures even greater investment by farmers for, inputs, services and finance.

Alternative path to profitability

The idea that an alternative to simply boosting productivity exists which can assist Australia’s professional Top 25% of farmers to stay profitable is becoming more apparent as farmers and some businesses look in greater depth at what our domestic and overseas customers are demanding. It’s not just about producing more commodity with less inputs but also understanding the holistic nature of farming and guaranteeing food safety and quality, combined with recognising consumers’ credence value aspirations for food such as environmental integrity, higher standards of animal welfare, and transparency and traceability from farm to plate.

Here are some examples:

- Dairy farmer Roma Britnell, Woolsthorpe, Vic on the WCB takeover offer by Saputo and counter offer by the Murray Goulburn farmer co-operative in October 2013. “Having ownership post farm gate is imperative to farmers’ ability to influence the price they receive and therefore their future business sustainability. We don’t and can’t influence the international milk price. However, ownership of the product further along the supply chain by farmers does determine how much of the profit (and losses) stay with us. Without an efficient farmer-owned model to sell through we would be at a significant disadvantage. It seems in Australia we are not listening. Everywhere else I went this was considered a no brainer.”

- Launch of Green Pastures milk into Coles supermarkets in November 2013 – the company’s five founding family farms operational philosophy: “To create a world-class brand we can be proud of, a brand that sees the dairy industry (and later other farming sectors) be economically viable again for farmers – where farmers are fairly rewarded for effort and our communities can thrive for the benefit of all Australians. To lead the world in how we farm, that is, to farm – and inspire other farmers to join us – in a way that significantly reduces our carbon footprint, our chemical and other impacts on the environment and creates better farms with nutrient rich healthier soil, animals and produce. To raise consumer awareness about the critical impacts of how we farm on human health and give consumers products that are truly cleaner, greener, better and healthier for themselves and their children. Lastly, to inspire our children and give them a future in farming.”

- KPMG Asia business group leader Doug Ferguson speaking at launch of a study by KPMG and Sydney University into Chinese foreign investment in Australian Agriculture: The consequence of the shift from food security to food safety is a shift in commercial strategies. Food security was served by the export of bulk agricultural commodities and was heavily reliant on government to government policy initiatives. Food safety is market driven and reliant on industry initiatives and niche strategies. (Chinese) consumers have choice and are concerned about the safety of their food. They prefer foreign-produced and imported processed food due to low levels of trust in locally grown and made products.

- Doug Clarke, chairman Western Australian Grains Group after visiting China in 2013 to study opportunities for Australian wheat in the Chinese flour market: “We went over there basically to get a better feel for what wheat end-users wanted and to try to secure direct access to Chinese wheat markets. In the long-run we’re looking to value-add our grain products. We visited millers who told us the majority of the wheat they used was now from Canada and the US. A decade ago they were sourcing as much as 30% of their wheat from Australia. However, they said the quality of the Australian flour was reducing and it was becoming yellower. They (Chinese millers) said they would like to deal directly with farmers to import the wheat they require.

- Rabobank analyst Michael Harvey in November 2013 on opportunities for food into Indonesia: Australian food and agricultural industries will need to begin a “journey of diversification” to help unlock more value of this trade opportunity. Capturing more value is critical. Extracting more value from the market will be vital in providing a sustainable return to the Australian supply chains. The Rabobank report says food and agricultural exports could increase by a further 50 per cent in the next five years. To fully capitalise on these opportunities, Rabobank says, the focus should be on ‘the value, not the volume’, with an aim to develop more strategic partnerships within Indonesia, build stronger government-to-government relations, to continue the shift to value-added products and to extract maximum value from supply chains.

- Kangaroo Island Pure Grain business philosophy: Kangaroo Island Pure Grain was established in 2009 with a mission to provide premium returns to Kangaroo Island grain growers, encourage existing farmers to increase their grain production and encourage others to enter the industry. The company receives, stores and classifies the majority of KI grain grown and sold into the domestic and key export markets, including Asia and Japan. We have established a ‘paddock to plate’ system that enables us to monitor grain production from seeding to harvest and storage and quality testing. And we guarantee our grain contains no genetically modified material and has been grown with minimum chemical inputs. In its 2013 marketing initiative called the Three Amigos KI Pure Grain is supplying wheat to boutique flour miller Lauke Flour who in turn supplies Skala bakery which has high profile clients like Qantas. Lauke is also looking at the possibility of marketing a KI Pure Grain branded flour. Lauke Flour owner Mark Laucke says more groups of farmers need to consider value-adding alliances such as this one. “Farmers can’t expect to force a commodity into the market and get a premium for it. They are facing rising costs and won’t survive unless they become more focused on quality to the end-user.”

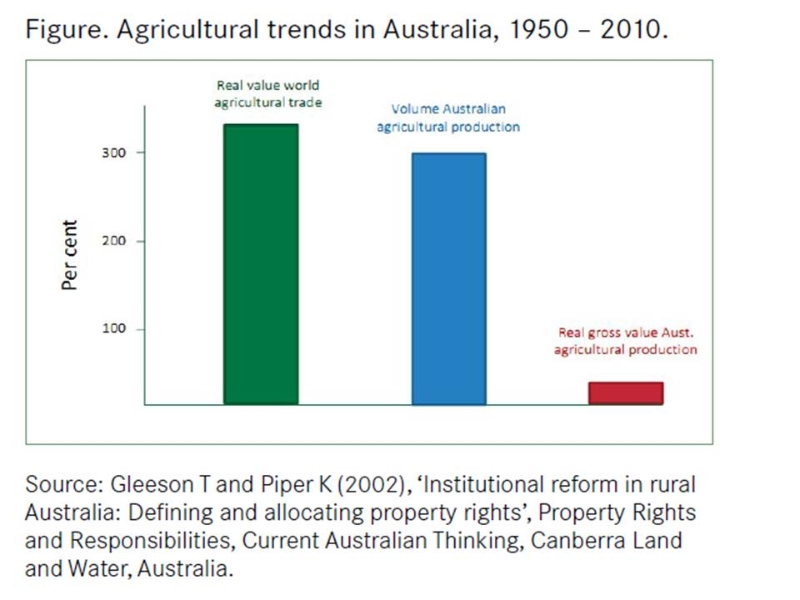

- Australian Land Management Group CEO Tony Gleeson speaking at the Queensland Landcare conference: “Even with two-and-a-half to threefold increase in agricultural production in Australia the real gross value of agricultural production – the gross value corrected for inflation – has changed very little, Figure 2. We should well ask why this lack of change in real gross value will not be repeated over the coming decades. Notwithstanding the growth in world trade, production and productivity, there has been a steady decline in aggregate real net farm cash income. The natural resource base has deteriorated and many argue there has been a comparable deterioration in social capital. The lesson we might take from this is that Australian agricultural producers should respond to market requirements and price signals rather than to calls for increased production. In other words, governments, industry and landholders need to focus on profit and ecological integrity. For Australian agriculture this involves working back from consumers and customers along value chains, preferably in higher priced discerning markets where competition is based on value rather than on price alone.

- Ben Calcott, western Qld cattle producer commenting on the 2013 drought. “There is no ‘fat’ left in the agricultural system to plan for bad years, nor to recover from them. Profitability was eroded many years ago, and the industry has limped along on the back of cash reserves, cost cutting and equity ever since. The process is very nearly at an end. The capacity to endure further losses does not exist. The profitability crisis in agriculture can be linked to virtually every one of the issues that regional Australia is currently facing…and to the fact that businesses are no longer in a position to properly manage in the natural environment that they are built on. The marketing of agricultural product has not been helped, at least in some industries, by a lack of sophistication among vendors. Prices offered have been accepted without regard to normal business practices. There has been no demand to maintain profit margins.

- JBS Australia director John Berry commenting in Beef Central on the launch of the Great Southern brand for beef and lamb. “Great Southern products represented a strategy change from marketing meat commodities to a market-focused brand strategy with industry and commercial systems that met customer end requirements. We are underpinning a system to ensure consistency, quality and integrity in what consumers ultimately eat. It’s brilliant that we can re-position grassfed out of Australia as a premium product. ” JBS Australia farm market assurance manager Mark Inglis said the Great Southern program aimed to get higher returns for quality assured grassfed product for producers. “If we can get more for that product at the other end, it is about sharing that percentage back to the producers.” A network of mostly southern Australian producers will consign beef and lamb direct to JBS Australia works in Victoria and Tasmania under guidelines ensuring quality, traceability, animal welfare and food safety.

Those accepting the existing commodity culture, that is for Australian farmers to simply aim to produce more non-value added products like grains and live animals should not be comforted by another Australian Farm Institute report by Mick Keogh and Adam Tomlinson which reviewed live export opportunities: “In recent years there has been a structural shift in the global trade of bulk agriculture commodities. Nations that rely upon agricultural imports for their food supplies are increasingly seeking to import raw or minimally processed commodities that are then processed within that nation, prior to distribution and sale to consumers. This trend towards the increased importation of raw or minimally processed products is observed for most major commodities including grains, oilseed and sugar, as well as meat.

“For grains this shift is demonstrated by the fact that the growth in global bulk wheat exports has been consistently higher than the growth in flour exports. Major grain importing nations have developed flour milling capacity for a range of reasons, and this is increasing demand for the raw commodity rather than processed product. Governments of major agricultural importing nations have been generally supportive of this shift towards the importation of raw agricultural commodities, as it creates more jobs in the domestic economy and allows a greater level of control over food supply chains,” Keogh and Tomlinson said.

Ironically the authors contend this approach by overseas governments is in fact a positive development for the live export industry. The reality is this action puts pressure on keeping live export animal prices as low as possible so value-adding by agri-businesses in importing countries is maximised.

The same message comes from south east Asian flour millers who purchase large volumes of Australian wheat. Their strategy is to purchase specific high quality, commodity grain from Australia at the lowest possible price (and sometimes blend it with lower priced grain from Eastern Europe), then value-add to it domestically to maximise the profitability of their own processing and retailing businesses. For example Dr Nasir Azudin told the 2012 Australian Grains Industry Conference that Indonesia’s flour milling capacity has expanded from four millers in 2000 to 15 millers in 2012 with 7.7 million tonnes capacity. Not only that, these companies were constantly improving technology and quality assurance and moving further along the value chain by setting up their own R&D divisions for product development and manufacturing as well as retailing consumer products, sometime in their own outlets.

The November 2013 Rabobank Report alluded to what’s happening without making the commodity culture connection with grains and live cattle exports from Australia: “Indonesia’s middle income population is expected to surpass 140 million by 2020 …. (it) is driving the rapid expansion of the modern food retail and service sector. Indonesia’s significant increase in per capita disposable income is encouraging for a preference for western-style foods, with flour and protein-based products such as cakes, biscuits, pizza and processed foods, including a wide range of snack products, becoming more and more popular. In recent years, many QSR (quick service restaurant) operators have increased their presence in Indonesia and are now looking to expand further beyond the island of Java. According to Rabobank, there will be more western fast food chains – Indonesia currently has 5,890 fast food outlets and this number is expected to reach 9,100 in 2017.”

The commodity culture may work to maintain farm profitability in the US and EU where governments subsidise prices for livestock and grains and wages are lower than in Australia, and in South American countries where wages are low and workers conditions often unregulated. But in Australia the commodity culture is a recipe for eventual business failure as costs constantly increase and is usually precipitated by an extreme environmental event, drought being the most common.

The irony is the commodity culture lesson for Australian farmers was made obvious in the rise and fall of the nation’s foundation and pre-eminent sector – Merino wool, which collapsed in 1991. Industry participant, historian and analyst Charlie Massy understood what a ‘commodity culture’ is and described what it means in in his 2011 published book “Breaking the Sheep’s Back”: “This is a culture geared to (product) mediocrity; a culture which ignores the best business practices. It is a culture that has handicapped the attributes of an extraordinary fibre. A key reason why the wool industry has continued to decline so dramatically since 1991 is this commodity culture, which prevents the industry from responding to a changing environment and to competitive challenge.”

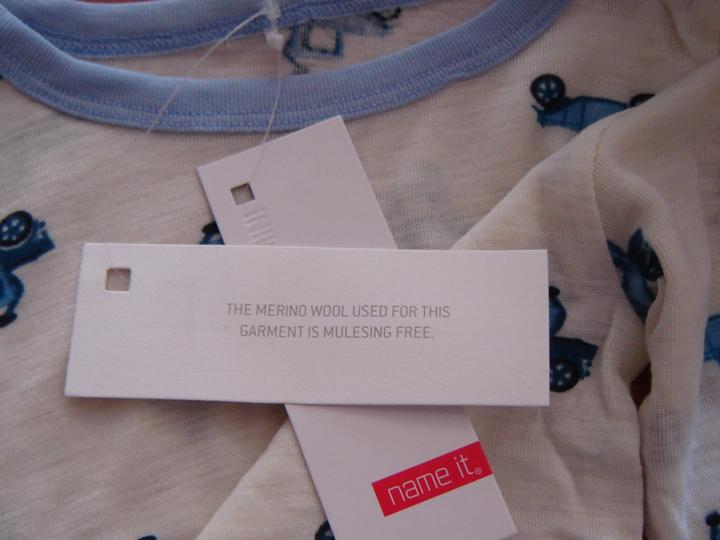

Two issues in the Merino sheep sector which epitomise its commodity culture are: its failure to adopt a breeding strategy to eliminate the need for mulesing and the subsequent loss of market opportunities amongst textile manufacturers, retailers and consumers demanding Merino wool from unmulesed animals. Secondly, the industry’s unreserved support for continuing sheep live exports despite constant animal welfare abuse events in overseas countries and its failure to enthusiastically promote as an alternative greater on-shore processing and sheep meat value-adding.

Take home message

Australia’s domestic and export markets for red meats, dairy, grain, and fibres can be divided into two major components, products identified and highly transparent for food safety, quality, and credence values with the farmer involved in the value chain; and commodity products that are good quality but undifferentiated for most other attributes with the farmer’s involvement ending at the farm gate. The former has a future for improving professional farmers’ business profitability in conjunction with ecosystem health. The later will benefit overseas processors and retailers and leave part-time enterprises looking for more off-farm income to survive and putting in jeopardy ecosystem health as productivity is pursued at all costs in an increasingly variable climate.

BOX STORY

OTHER EXAMPLES DEMONSTRATING AN ALTERNATIVE PATH TO FARM PROFITABILITY:

- Consolidated Pastoral Company (CPC), one of the largest beef producers and live cattle exporters, Annual Report: CPC’s vision is to be a world class, market-focussed producer of high quality, grass fed cattle and a quality beef supplier to diversified markets. Our strategy is to transform the company over the next three years from being a traditional farm led producer to a more strategically and commercially focussed market making organisation which understands our markets and produces the right product at the right time in the right location to meet our customers’ needs.

- AACo , the largest beef cattle producer and live exporter; at its annual general meeting chairman Donald McGauchie said: “It is quite clear that AA Co can no longer continue to be just a cattle producer. The focus of the board is to improve the returns, and return on capital is paramount. AA Co’s strategy is to diversify away from capital intensive primary production by increasing its exposure to higher-margin, less-cyclical assets with a higher return on capital. The primary focus is on vertical integration of AA Co’s beef business, including: capturing additional margin from downstream processing (including by-products); increasing direct access to international export markets, in particular in Asia; improving productivity from managing supply chains across its pastoral, feedlot and processing assets; and focussing on brand and market development to facilitate new and stronger relationships with high value food services customers in overseas markets. In November 2013 the impact of this decision was revealed during AACo’s report for its six months of operation to September 30 when it revealed a net loss after tax of $31.6 million. The result it said was adversely affected by a 12 percent decline in average live weight cattle prices during the period, which contributed to a $20.4m drop in revenue for live cattle sales. The poor live cattle result was partly offset by the strong performance of the company’s Branded Beef division which improved gross margins by 323pc. The company said the success of the Branded Beef business continued to validate AA Co’s strategy of moving from being a pure cattle-producer pastoral company to a vertically integrated beef, processor and marketer.

- Former Meat & Livestock Australia senior staff member for 33 years Tim Kelf, in Beef Central on beef opportunities in China. “I’ve always taken the view that Australia’s opportunities in mainland China will at least for a period be at the higher-quality end, at least until the nature of the local supply and the import trade evolves more. The good news was that beef is becoming a real status food product, in the eyes of many Chinese consumers. Particularly in the country’s more northern regions, Chinese people were increasingly putting beef on their tables and menus as a status item. That was partly because it cost more than other popular protein options like pork and chicken, but also because it was much harder to source. All this suggests that Australia’s future in beef trade with China remains squarely at the higher end of the market, via direct trading channels into the food service and retail segments. Our (MLA’s) strategy has focussed on the higher-end chilled beef trade. If we can win the five-star segment from US beef…the residual effect, we believe, will be that they will follow that preference when making purchases at higher-end retail supermarkets. As the modern retail supermarket sector grows in China, that’s where Australia should get its retail growth”.

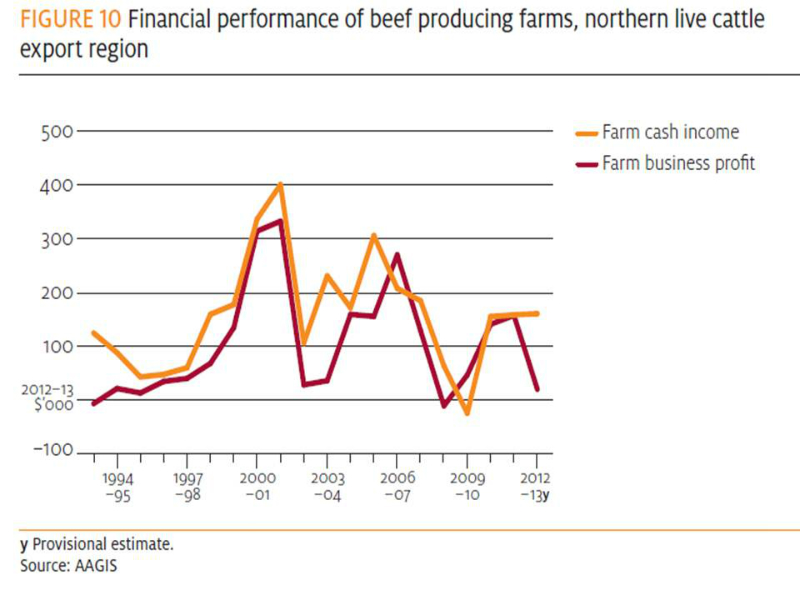

- Chris Honey – Partner, McGrathNicol corporate advisors, commenting on the northern Australian beef industry in December 2012: Even before the seismic upheaval caused by the Australian Government’s ban on live cattle exports to Indonesia in June 2011, the northern beef industry was showing the classic signs of a sector with deeper, underlying structural problems. Traditionally producers had done reasonably well, but like most sectors of Australian agriculture, they were subject to the vagaries of drought and commodity prices. Scale was often large but this did not necessarily translate into high financial wealth.

However, a dramatic increase in land prices over the last decade turned many long-established operators into paper millionaires; saw the entry into the market of the price-distorting management investment schemes; and attracted the interest of overseas investment funds. New live trade markets combined with a dramatic increase in per hectare productivity helped to buoy the outlook. A recent survey by the Queensland Rural Adjustment Authority estimates average debt per cattle enterprise is now $1.4 million, having grown by 20 percent in the last two years alone. The same study estimates debt per beast has risen from $240 to $647 in the last decade. Crucially there has been no discernible increase in the long-term average income over the same period. But more recently, property values have begun falling. The challenge now facing northern beef producers is to manage high debt-servicing costs and the need for greater short-term working capital support, through a period of low and uncertain incomes. As serious as it has been, the disruption to the live export trade is not the problem itself. The main problem for the northern beef industry has been an overreliance on the live trade and the change in the financial structure of many businesses dependent upon it. This has severely impacted their ability to adapt.

There remain many extremely competent and profitable operators in the industry, such producers can be identified by a range of operational and financial factors including: a focus on overall enterprise profit and the recovery of overheads rather than just on herd productivity; an absence of over-reliance on a particular market and an ability to adapt as markets change.

- Australian Organic Market Report 2012: The Report finds 3 in 4 organic products are now bought at supermarkets, representing an ongoing market trend as consumers look for organics. It confirms organics is worth $1.27 billion to Australia and is predicted to grow by up to 15% each year, putting it within the top 5 growth industries in Australia. Farm gate sales of organic products have risen by 34% since 2010. The meat sector has experienced a dramatic increase. Sales of beef are up by 111% to $72.7 million, lamb is up by 64% to $18.6 million, wine grapes are up 107%, dairy up 63%, and poultry has increased by 15%. Australia has the largest area of certified organic land in the world. Dr Andrew Monk Australian Organic director and Report co-author says: “Shoppers are voting with their wallet and supporting foods and fibre that are not only quality products that are good for us but are also good for the environment.

“Sixty-five per cent of Australians have bought organic in the past year and more than a million Australians do so regularly. Three prior noted top barriers to buying organics – price, ease of access/availability and trust in the product being organic – have all been reported as being lesser barriers for consumers than in 2010. Trust in organic certification and consumer awareness of standards and certification has increased considerably.