Glyphosate becoming lost to US farmers

The results of over-reliance on glyphosate in genetically modified (GM) crops in the US has driven home the unavoidable truth that herbicide resistance cannot be managed with herbicides alone. Thirty years ago, herbicide-resistant weeds were a mere academic curiosity, herbicides dominated weed control (and always worked well) and GM stood for General Motors.

The present reality is that weeds have evolved resistance to 21 of the 25 known herbicide modes of action that underpin 148 different herbicides. Herbicide-resistant weeds have now been reported in 63 crops in 61 countries. In another significant shift, GM is now intimately associated with ‘glyphosate-resistant’ soy, cotton, maize and canola, which in the US and Canada has become the most rapidly adopted technology in the history of agriculture.

Glyphosate-resistant weeds now dominate herbicide resistance research, with 24 species across 18 countries reported as resistant to glyphosate. No longer an academic curiosity, herbicide-resistant weeds represent a major annual threat to crop production, profitability and sustainability across the globe.A recent US and Canadian survey revealed that almost half of all growers in these countries suspect they have glyphosate-resistant weeds in their GM cropping systems. In the US, 25 million hectares – about the total area of cropping in Australia – is infested with glyphosate-resistant weeds.

The biggest weed problem in the US is Palmer amaranth, a succulent that emerges over seven months, grows at a rate of three to 10 centimetres per day and generates one million seeds per plant. Glyphosate-resistant Palmer amaranth is now in 26 US states and is spreading at a fast rate. In Argentina, glyphosate-resistant Johnson grass is also a rapidly growing issue.

Many now believe glyphosate is lost to the US, with Argentina and Brazil likely to suffer the same fate given their high adoption of glyphosate-resistant crops.

In an ironic twist, some US growers have had to resort to the age-old practice of hand-weeding and deep tillage to manage herbicide-resistant crop weeds. In Tennessee, where nearly all growers practised no-till five years ago, more than half have now had to return to deep tillage to bury herbicide-resistant weeds.

In Australia, following two to three decades of reliance on glyphosate for fallow and pre-sowing weed control, five weed species have developed glyphosate resistance in the northern growing region, threatening the viability of no-till farming.

Glyphosate-resistant ryegrass is also emerging as a significant issue along fencelines, roadsides and train tracks across Australia, which have for many years been controlled using glyphosate. There is a risk that these resistant weeds could jump the fence into cropping paddocks.

Multiple resistance to in-crop herbicides is now the norm in annual ryegrass and wild radish populations in Western Australia and increasingly across southern Australia after decades of herbicide use in continuous-cropping, minimum-tillage systems.

How it happened

It may seem like stating the obvious, but it seems we often forget that herbicide resistance is inevitable when herbicides alone are used to control weeds.Before the introduction of GM soybeans in the US, 19 different herbicides were being used on soybean crops. Following the widespread adoption of glyphosate-resistant soybeans, fewer than five per cent of soybean growers continued to use a herbicide other than glyphosate to control weeds. Over-reliance on glyphosate alone has also been the norm for GM corn, canola and cotton.

Before minimum tillage and continuous cropping became standard in the northern WA wheatbelt, weeds were controlled with cultivation, sheep and herbicides. Following the move to no-tillage and permanent cropping, in-crop selective herbicides became the predominant form of weed control.

Weeds have an inherent capacity (developed over millions of years) to develop resistance mechanisms to attack and will even develop ways to combat mechanical control if the method is used consistently for a long enough period. The only way to extend the life of any herbicide and play weeds at their own resistance game is to use a range of chemical and non-chemical methods, such as rotating herbicides, harvest weed seed control and growing competitive crops, to fully control weed populations. If weed densities are kept low, then the likelihood of resistance genes evolving within the population is also kept low, and herbicide usefulness is extended.

Herbicide resistance would not be a problem if new, effective herbicides became available as old herbicides became redundant. We could just keep replacing old chemistries with new ones to control weeds.

But it is extremely unlikely that new modes of herbicide action will become available in the near future. Also, European regulators are forcing the removal of some chemistries, reducing the number of herbicides at our disposal. It is therefore critical that we extend the life of herbicides for as long as possible.

The US has learnt the hard way that over-reliance on one herbicide (and one cropping system) for weed control can lead to a disastrous situation for crop production. A recent survey of US growers showed that, disturbingly, many still expect a silver (chemical) bullet to be developed to replace glyphosate. This is understandable given that glyphosate itself became available during the ‘golden age’ of herbicide discovery in the 1970s and at a time when resistance to selective herbicides had become almost unmanageable.

But the reality is that there are no new modes of herbicide action on the horizon. The previous new herbicide mode of action was developed more than 30 years ago, and since then there has been an 80 per cent drop in the number of companies actively pursuing new chemistries.

Herbicide development is expensive – about $250 million from discovery to commercialisation – and with the market largely captured by glyphosate-resistant crops, new herbicide discoveries just have not been a viable business activity in the short term.

The over-reliance on glyphosate in GM cropping systems, extensive presence of glyphosate-resistant weeds and the lack of new herbicides on the horizon have combined to bring the US cropping system to a tipping point. While GM crops with multiple stacked-resistance genes will buy time, they are not the long-term answer to herbicide resistance.

Integrated weed management needed

Herbicide resistance will not be solved with herbicides. Only integrated weed management and a zero tolerance for weed escapes will enable long-term control of resistant weed populations.

Australia can learn from the US experience with glyphosate resistance and profit from extending the life of this valuable knockdown herbicide. Like the US, our over-reliance on single herbicide modes of action and a lack of diversity in our cropping systems have led to significant herbicide resistance issues. We are second only to the US in our number of herbicide-resistant weed species. Thankfully, glyphosate remains effective against most of our cropping weeds, but losing it to widespread resistance would be a disaster for pre-sowing and fallow weed control. Extending its useful life is dependent on integrated weed management.

Unlike the US, Australia has responded to its herbicide resistance problem not by expecting a new chemical solution but by developing innovative non-chemical weed control measures.

Necessity has bred invention with the development of several harvest weed-seed systems – from chaff carts through to the newly released Harrington Seed Destructor – all of which have the capacity to reduce weed populations to almost zero when used properly. In some instances, growers with a significant herbicide resistance problem have been able to reduce their weed seedbanks so significantly that they can now dry-seed with confidence and sometimes have no need for in-crop weed control.

Targeting weed seeds at harvest is now a major focus of grain producers in WA and increasingly in southern Australia. The majority of these growers are optimistic about the future of grain cropping in their regions, despite high levels of herbicide-resistant weeds.

We will benefit from exporting our expertise in these systems to countries such as the US, Canada, Argentina and Brazil as they face the challenging future of increasing herbicide resistance and fewer chemical weed-control options.

Find out more

Professor Stephen Powles, 08 6488 7833, stephen.powles@uwa.edu.au . Source: GRDC

Resistance rising across Australia

Australia has the second highest number of herbicide-resistant weeds in the world – sitting only just behind the US. Twenty-five weed species have been confirmed resistant to one or more herbicides across Australia’s cropping regions.

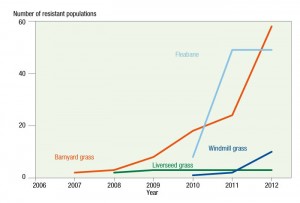

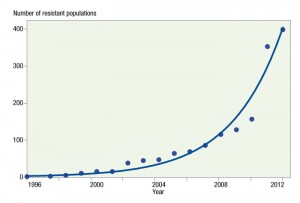

Glyphosate-resistant weeds are on the rise across Australia, with six species now confirmed with resistant populations – annual ryegrass, barnyard grass, liverseed grass, windmill grass, brome grass and fleabane (see Figures 1 and 2). Weeds with resistance to glyphosate have been found in every mainland Australian state. There are 347 documented glyphosate-resistant populations of annual ryegrass across Australia.

Of these cases, nearly half come from roadside verges and cropping fencelines – reflecting the long-term use of glyphosate to control weeds on property firebreaks and council verges. Australia has 612,000 kilometres of road considered at risk of developing weeds with glyphosate resistance, so the potential problem is huge.

In addition, market research has found many land managers are poorly prepared to deal with the looming crisis. The majority of the remaining cases stem from long-term use of glyphosate in broadacre cropping systems, particularly summer fallows. Glyphosate is an excellent herbicide that helps keep management costs down, but there are no easy replacement options available.

Glyphosate-resistant weeds in chemical fallows are threatening the viability of no-till cropping systems in the northern cropping region. Resistant annual ryegrass, barnyard grass and flaxleaf fleabane top the list. Glyphosate-resistant windmill grass, and to a lesser extent liverseed grass, are also increasingly being reported

The rapid development of glyphosate-resistant weeds and species’ shift to glyphosate-tolerant status will have a large impact on the cost and ease of weed management in Australian cropping systems. It is critical that the life of this valuable herbicide is extended via integrated weed management.

Find out more:

Chris Preston, 08 8313 7237, christopher.preston@adelaide.edu.au