Food Green Paper fails industry analysis test

By Patrick Francis

The National Food Plan Green Paper should be amongst the top four policy documents prepared by the federal government for discussion amongst stakeholders and the general public. Food is core business for everybody everyday – no other industry has the same relevance to a nation ‘s population.

Despite this the National Food Plan Green Paper is a major disappointment. That’s because its cross-sector analysis of recent past trends and projections for the future is deplorable. This means there is no opportunity for the reader to make any meaningful comparisons about effectiveness of recent policy agendas to build the nation’s food production and processing capacity and profitability. While there are an enormous range of perspectives to be embraced in such an important sector and issue for all Australians, this Green paper has not been prepared to the professional standards required.

The document could be summarized as saying:

- Food production and processing sector is in the main operating successfully

- There is no need for any major new policy initiatives to stimulate business profitability as government has in place the policies to take the sector forward.

- Consumers benefit from low cost food produced by the sector.

- Food production and processing here must be globally competitive.

- Food farmers will remain profitable by boosting productivity especially though adoption of plant varieties using genetically modified organism technology.

- Food processors will remain profitable by adopting technology to lower cost of production.

- Food production and regional processing will not be curtailed by removal of irrigation water for the environment under the Murray Darling Basin Plan or removal of agricultural land for conservation under the National Reserve Program.

- The growing middle income sectors in Asian countries are going to demand more of the food commodities and processed foods Australian businesses produce.

- The impacts of climate change will be countered by greater investment in Research and Development to boost productivity and international food production and processing competitiveness.

The self-congratulatory nature of the Green Paper demonstrates it has not been written for major reform, but as a promotion for the status quo. Typical examples are:

- the Australian Government has recognised that investment in infrastructure is critical to Australia’s economic performance and has spent record amounts to improve Australia’s transport infrastructure

- Australia’s agricultural counsellors are a network of government representatives situated around the globe who work to gain and improve market access opportunities for Australian food producers

- The government will continue investing in innovation to help the food industry find smarter ways to do business with products, processes and people.

Such self- congratulatory sentiments mean little as there is no evidence presented to demonstrate negative trends over recent years are being halted and/or positive outcomes happening. Lack of data is a feature of the Green Paper. What should have been presented is decade long trends about: farm and processor bank debt; return on equity; full and part-time employment trends; farm and processor business numbers; domestic versus overseas value adding to commodities; volume and value of imported ingredients and products; international versus Australian processing costs comparisons for major foods like meats, flour, oils, milk products; and the farm gate price share of the consumer dollar for fresh foods like fruit and vegetables, milk, meats, bread, juice, eggs.

The evidence that is available about food production and processing, but not included in the Green Paper, is that the sector’s businesses are in the main under considerable financial pressure as a result of falling real commodity prices, rising input costs, increased government regulations, rising labour costs, and lower retail margins. Constant government advocacy of lower food prices for consumers, without any reference to farm gate price share and the Consumer Price Index, is having a significant impact on producer and processor margins and is a major threat to future participation by Australian farmers particularly in the fruit and vegetable, milk and bread sectors. Many supermarkets home brand staple products are being sold for unrealistic prices which suits their business and share price agendas but is pushing many farm suppliers and processors towards extreme rationalisation or even out of business.

A clue to the financial reality facing farmers comes from USDA Economic Research Service. It regularly measures the food dollar share accruing to farmers from the sale of raw food inputs (the farm share), with the remainder accruing to food supply chain industries involved in all post-farm activities that culminate in final market food dollar sales. Such analysis is not available in Australia but the trend would be similar. In the US farmers share of the consumer dollar has been declining for decades, figure 1.

Key word analysis

Analysis of key words for the sector demonstrates biases and lack of investigative depth involved in writing the

Green Paper. Examples include:

Energy cost – 0

Labour cost 0

Business debt 0

Farm gate price 0

Renewable energy 1

Soil health 2

Government regulation 3

Profitable 7

Affordable food 14

Biotechnology 14

Processor 20

Climate change 95

Farmer 103

Productivity 212

Consumer 218

This clearly demonstrates the Green Paper ignores the essential business fundamentals for viable domestic food industry – financial competitiveness and domestic investment. Ironically over the last five years overseas companies and investors have recognized the value of Australia’s post farm-gate food sectors and become dominant players. This has been most obvious in grain accumulation and marketing, red meat processing, fruit and vegetable processing, and milk manufacture. The early consequences are rationalistion of processing plants which for efficiency purposes could be argued as a positive but for regional employment and farm gate prices is having severe negative consequences.

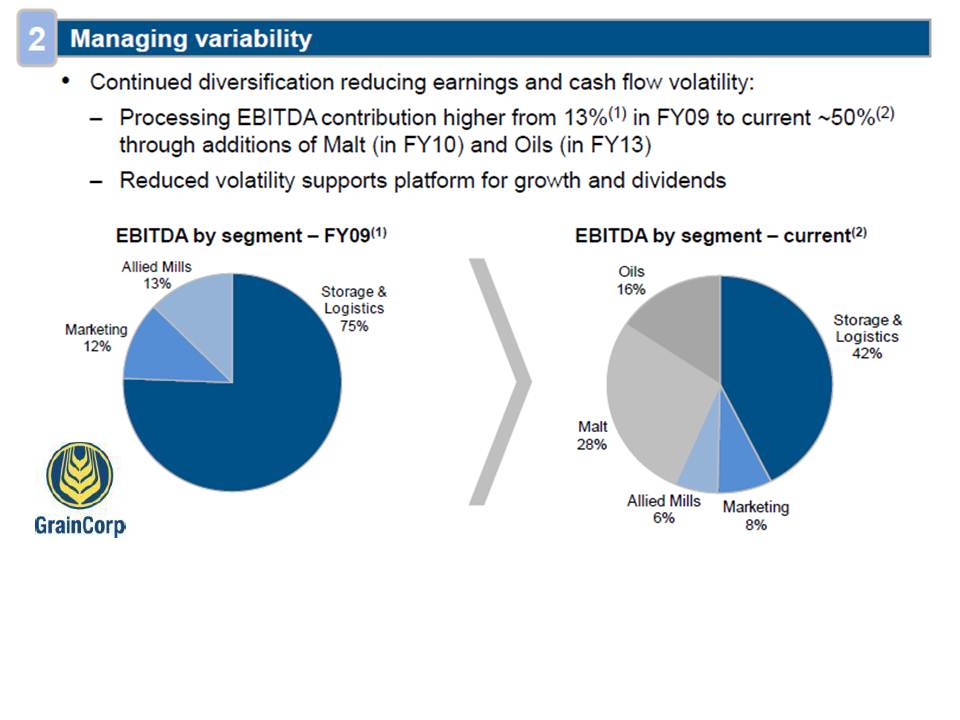

While only two Australian owned grain accumulators remain, one, GrainCorp a publically listed company, demonstrated where profit will be generated in the future. Ironically its 2012 annual report did not mention future farm gate grain prices, but highlighted profit growth in grain storage and logistics, marketing and processing. The company has diversified its business components to suit this business model, figure 2.

Policy contradictionsThe rationalisation taking place in food processing sectors highlights another issue with the Green Paper, policy contradictions. The government’s Securing a Clean Energy Future Plan is about reducing the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions. Rationalistaion of the food industry is likely to result in greater sector emissions as fresh food and livestock are transported greater distances for processing, and once processed transported again with refrigeration to wholesalers and retailers distribution centers and from there to retail outlets. The concept of local food processing precincts, with waste products being combined for regional renewable energy generation and organic fertiliser production is not mentioned.

The failure of successive Federal governments to learn that local processing has important social, environmental and farm business benefits, is contagious. It is currently playing out in the live animal export sector, where the demise of local processing opened the door for a live export sector, which in turn through its simple business model has compromised livestock welfare and alienated many consumers, reduced employment in Top End towns which once had abattoirs, and added risk to cattle business profitability by providing only one market outlet. To overcome the shortcomings of the live export trade, a new processing plant is being built near Darwin and another is mooted for far north west Queensland. Thirty years ago at least two abattoirs were operating in the Top End.

It is highly likely the processing plants for milk, fruit and vegetables, flour and livestock that have recently been closed in eastern and south eastern Australia will end up in another 20 – 30 years being replaced for social, environmental and business reasons.

Another example of policy contradictions and lack of research into the Green Paper is highlighted in Section 7 “A strong natural resource base”. On the one hand the government acknowledges changes in farming practices have occurred, particularly since 2000 to improve ecosystem services in conjunction with food production. But when it suits the authors argument about “Increasing agricultural productivity” it sinks the boot into farmers accusing them of allowing “ …increasing (land) degradation.”

On-farm productivity push

The strategy at play here is to divert the reader’s attention away from the fundamentals associated with profitable food production in favour of the time-honoured escape clause – boost productivity and all will be well. This also falls into the relatively ‘easy’ policy strategy of a ‘concerned’ government which shows its good will towards a sector by throwing research dollars towards it to improve productivity. This approach is conveniently less expensive, because productivity research is now usually a joint effort between governments and multi-national corporations who have a product to sell to farmers as a result of the research, for example genetically modified crop varieties.

In contrast, important research into improving soil health which has the potential to boost productivity and plant climate resilience with minimal commercial product input, is by comparison poorly supported.

A less obvious policy contradiction in the Green Paper relates to the government’s claim about “supplying the Asian century”. Such a claim needs to be treated with caution for a number of reasons:

- The major food exports from Australia – beef and wheat, are not basic foodstuffs for Asian consumers.

- In the meat sector wealthier Asian consumers are increasing consumption of chicken, pork and fish. Beef is a minor player and medium term projections for world demand are flat. In Australia and the US chicken has overtaken beef as the most consumed meat. It is difficult to see why this would change amongst the emerging wealthier Asian consumers. Opportunities have been developed for niche Asian markets by innovative Australian businesses eg high quality beef into the five star service sector, but this is not a major volume sector.

- While Indonesia is Australia’s largest market for wheat, more affluent Indonesian consumers are increasing consumption by purchasing what is referred to sweet products manufactured in Indonesia by millers and bakers. These local processors make their business profit by buying wheat at the lowest possible price. Australian wheat is often the most expensive, but its ‘average’ price can be lowered by blending it with lower cost wheat from former Soviet Union countries.

- Developing countries in Asia and Africa are increasingly involved with improving their domestic food production and minimising imports to essential raw materials. This is highlighted by the Indonesian government which in 2011 put restrictions on live cattle import specifications as a means of encouraging the domestic beef production sector. It is also has a program in place to increase rice production and eliminate rice imports. The Chinese government subsidies its farmers to grow rice and wheat to ensure these staples are domestically grown. Many of the Asian countries seen at markets for Australian food have Total Factor Productivity rates two to three times those of Australia, figure 3. This means that in many basic foods these countries are managing to keep pace with domestic demand. It is interesting the world’s most traded grains corn and soybean are minor crops in Australia. China is importing increasing quantities of these two grains and their processed products including those from biofuel processing to feed pigs and poultry. The issue of growing the grains in greatest demand around the world was not addressed in the Green Paper. Australia has significant potential for these two crops plus sugar and rice in northern Australia and the Murray Darling Basin if their development in conjunction with water resources is facilitated.

Figure 3: Improvement in agricultural total factor productivity is highly variable between and within countries. Many of the developing Asian countries have higher food output growth per year than Australia. Source: USDA Economic Research Service 2012.

In pursuit of developing countries becoming more food self- sufficient, developed nations are investing billions in research, extension and technology programs to improve production on smallholders farms. Not only is the support helping to improve output, but systems are being adopted to provide complimentary re-newable energy, heating and restore soil health. Successful programs, particularly those involving women farmers, are leading to improved family income, allowing for children’s education, improved child health, and greater rural employment. Programs facilitating communications technology adoption is improving smallholders’ product marketing opportunities and improved infrastructure like roads and grain storages are reducing the high incidence of food wastage.

The Green Paper’s most worthwhile contribution to the food debate is its coverage of global food security. It says the Australian government’s “most effective contribution …is through providing development and technical assistance to developing countries to improve their capacity to sustainable produce and buy food. It highlights an important fundamental of world food trade recently pointed out by Professor Lindsay Falvey that 90% of world food is not traded, but grown and consumed in the country of origin. While this doesn’t apply to Australia where approximately 60% of food produced is exported, it highlights farmers face a profitability dilemma under the current policy regime solution of simply growing more raw commodities.

There needs to be a change of emphasis from “more food” to higher quality food with credibly assessed consumer desired attributes including animal welfare, lower cost of production and processing, integrated regional processing hubs and infrastructure, and at the domestic level a fair share for the farmer and processor of the consumer’s food dollar.

Copyright Patrick Francis